eBook - ePub

Leading Schools in a Global Era

A Cultural Perspective: A Special Issue of the Peabody Journal of Education

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Leading Schools in a Global Era

A Cultural Perspective: A Special Issue of the Peabody Journal of Education

About this book

This special issue looks at the constantly changing face of education in the world today. Topics covered include educational values, cross-cultural studies, leadership, social impacts, and the role of technology in education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Leading Schools in a Global Era by Philip Hallinger,Kenneth Leithwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Investigating Principal Leadership Across Cultures

Over the past decade or so there have been calls for increasing attention to the study of educational administration across contexts (e.g., urban and rural communities, elementary and secondary school levels) and cultural (e.g., countries) settings (e.g., Greenfield, 1995; Hallinger, 1992; Hallinger & Leithwood, 1996; Hallinger & Murphy, 1986; Hughes, 1988). The reason for this interest is the realization of the diversity in schooling practices within and across different societies and, along with tremendous progress in world communication, the increased possibilities for collaboration with colleagues holding similar interests in varied global settings. As Hallinger and Leithwood (1996) noted, over the past 20 years there has been an increase in the cross-fertilization of approaches toward educational policy and practice across nations aimed at solving particular educational problems.

One of these, the belief that principals play an important role within the organizational structure of schools, has long stood in the folk wisdom of education. Several orientations toward studying the school administrator’s role have evolved over time. Studies before 1980 generally sought to describe the nature of the principal’s position and work (e.g., Crowson & Porter-Gehrie, 1980; Inbar, 1977; Kmetz & Willower, 1981; Wolcott, 1973) but did not attempt to link these descriptions to other processes and outcomes (Boyan, 1988; Bridges, 1982). In the early 1980s, a line of research focusing on the impact of the principal’s attitudes and actions on school processes and outcomes began to emerge. This shift in orientation toward the study of the principal’s role had two general sources. First, research on change implementation began to identify the important role principals play in school-improvement efforts (e.g., Berman & McLaughlin, 1978; Firestone & Corbett, 1988; Hall & Rutherford, 1983). Second, concurrent “effective schools” research conducted in both Great Britain and the United States concluded that strong principal leadership was among those factors within the school that made a difference in student learning (e.g., Brookover & Lezotte, 1977; Brookover et al., 1978; Edmonds, 1979; Rutter, Maugham, Mortimore, Ouston, & Smith, 1979).

In part driven by policymakers’ concerns over educational accountability (Glasman & Heck, 1992), and in part the result of researchers’ concerns that educational outcomes must be at the heart of examinations of administrative behavior and its impact on school improvement (Bates, 1980; Bossert, Dwyer, Rowan, & Lee, 1982; Bridges, 1982; Leithwood & Montgomery, 1982), studies on principal leadership expanded in scope conceptually, methodologically, and geographically (Hallinger & Heck, 1996a, 1996b) between 1980 and 1995. Studies on the principal’s role in school effectiveness, for example, were conducted in over 12 countries (e.g., Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Israel, the Netherlands, Singapore, United Kingdom, United States). The research demonstrated the impact of principals on a variety of school processes and school outcomes as well as other measures of effectiveness (e.g., Firestone, 1990; Greenfield, Licata, & Johnson, 1992; Johnson & Holdaway, 1990; Pounder, Ogawa, & Adams, 1995; Tarter, Bliss, & Hoy, 1989). Principal leadership was found to affect processes between the school and the outcomes it produces; however, this relation is more indirect than direct (Hallinger & Heck, 1996b).

Although the accumulated work on principal leadership, conducted within a variety of different cultural settings, has demonstrated the principal’s impact on a variety of school processes and outcomes, we nevertheless lack many details concerning how principals respond to their schools’ environmental contexts as they seek to shape organizational processes and outcomes. Moreover, we do not know how school leaders through their interactions with others contribute to shaping organizational processes and outcomes on a day-to-day basis. In response to this need, a third research orientation toward the study of school leadership has emerged over the past several years. This view (a) captures different aspects of leadership including “sense making,” cognitive and problem-solving processes, and the negotiation of power in school relations; and (b) employs differing approaches to the conceptualization and analysis.

In many ways, this orientation represents a reaction against dominant ways of thinking about administrative roles in the past—for example, the field’s preoccupation with more highly visible line administrators who hold the most power and authority (e.g., superintendents and principals) within the system (Marshall, Patterson, Rogers, & Steele, 1996). In part, this orientation also represents new strategies for understanding administrative problems not addressed previously through the other two research orientations. These perspectives include concerns with power, gender, and cultural concerns; contextually driven (vs. “privileged”) accounts of leadership; reflection; and cognitive practices in problem solving (Evers & Lakomski, 1996; Maxcy, 1995). Often, the goal is to “deconstruct” many of the previous notions held about school administrators. Because of these concerns, the emerging research from this orientation has used a variety of new approaches and lenses through which to understand school life. A substantial body of work from researchers in several different countries is beginning to accumulate from these stances, but it is generally not comparatively directed, often focusing, for example, on particular principals (Dillard, 1995) or a particular school context (Anderson, 1991; Blase, 1989, 1993; Greenfield, 1991; Gronn, 1984; Keith, 1996; Robinson, 1996).

The number of studies on school leadership conducted in different cultural and national settings has definitely increased over the past 15 years, yet few, if any, of those studies were designed to investigate school leadership comparatively. Of course, proposing a new orientation to comparative research on principal leadership is likely to open up a host of issues that will need to be addressed. The purpose of this article is to identify several conceptual and methodological issues in beginning to investigate leadership processes and their impact across different cultural settings. More specifically the article addresses three questions:

1. How do we view research on school leadership (e.g., its research questions, models, epistemological frames, and methods)?

2. How do we define school leadership in comparative (cultural) studies, and what theories or models are useful in understanding school leadership processes comparatively?

3. What types of methodological issues are likely to surface in conducting studies across cultural or national settings?

Developing a Framework to View the Research

The objective of science is to understand the world in terms of its regularities and to formulate explanations of what has been observed (Hoy, 1996). Empirical knowledge about school leadership is created through the interplay of our theories and models about school leadership (i.e., theoretical models), our means of studying it (i.e., methodology), and our underlying assumptions about how we know. Different sets of assumptions lead to different orientations toward theoretical models, research questions, and methods of collecting and analyzing data. Of course, our thinking about these issues is also embedded in our cultural conditions and circumstances (e.g., Gronn & Ribbins, 1996; Hallinger & Leithwood, 1996). Different sets of assumptions lead to different orientations toward the research, such as theoretical models, research questions, and techniques for collecting and analyzing the data. Thus, the explication of methodology is related to epistemology, or basic theories of how knowledge is constructed and the interpretive framework that guides a particular research study (Everhart, 1988; Harding, 1987; Lather, 1991). It concerns the process by which we construct knowledge.

As suggested previously, earlier research orientations toward the principal’s role focused on the nature of their work and the effects of administrator actions. The dominating view of leadership within the organizational structure over the past several decades has been described as primarily functional—that is, suggesting that leaders’ values and actions impact on other actors and processes within the school (e.g., Ogawa & Bossert, 1995). This was perhaps best captured in the instructional leadership model of the principal’s role that dominated researchers’ attention in the 1980s (Hallinger & Heck, 1996b).

Recently, however, in the social sciences an enormous amount of criticism has been directed at traditional scientific conceptualizations, methodology (e.g., positivism, hypothesis testing, quantitative methods of analysis), and constructions of knowledge (Burnstein, 1983; Denzin & Lincoln, 1994; Foster, 1986; Greenfield, 1980; Habermas, 1975; Lather, 1991). Prolonged criticism has also led to new ways of thinking about knowledge construction and the role of the researcher in the scientific process (e.g., Jensen & Peshkin, 1992; Lather, 1991; Roman, 1992). Parallel to these criticisms in the social sciences, today there is considerable interest among researchers in educational administration about the interplay among leadership models, epistemological stances (e.g., functionalism, feminism, postmodernism), and methodology (e.g., empirical-analytic, interpretive, critical), resulting in considerably more flexibility in studying the principal’s role (e.g., Anderson, 1991; Blase, 1989; Dillard, 1995; Greenfield, 1991; Hoy, 1994; Leithwood, 1994; Marshall, 1995; Maxcy, 1995), as well as school leadership exercised by others (Hart, 1994; Pounder et al., 1995). These issues are also drawing increased attention from researchers interested in investigating school leadership in diverse settings (e.g., Bajunid, 1996; Hallinger & Leithwood, 1996; Heck, 1996; Walker, Bridges, & Chan, 1996).

Within our field, it is not clear yet what the contribution to knowledge of several new approaches will be, or whether thinking about school problems in new ways will aid in finding useful solutions for practitioners. A framework for understanding the various approaches to the study of school leadership, however, can be useful in helping researchers make sense of the empirical work that has been conducted and in providing a guide for research that looks at comparative aspects of the role across cultural contexts. How studies are conceived in terms of their research orientation and underlying conceptual models and how they are conducted affect what is found.

Fifteen years ago, Bridges (1982) raised the concern that much of what was being done in educational administration was atheoretical and poorly conducted. Whereas knowledge has accumulated over the past decade or so on the effects of the principal’s leadership, the types of research questions asked (e.g., what is the effect of the principal’s beliefs and actions?) generally focused on student achievement outcomes (Hallinger & Heck, 1996b).

Because of this concern, the studies were primarily conducted through quantitative methods and from a rather limited epistemological (or philosophical) perspective. Researchers were basically addressing a blank spot in the literature (Wagner, 1993). Of course, the “blind spot” (Wagner, 1993) of this orientation toward the effects of leadership was sense making within the organization—that is, how leadership is socially constructed by the various participants in the school setting. Moreover, one could also argue that looking at leadership practices comparatively also represents an attempt to address a blind spot for previous research on school leadership. That is, despite considerable work done within diverse cultural settings, none of it really attempted to look at leadership comparatively.

As Wagner (1993) suggested, a matrix can be developed representing traditions of inquiry, their research orientations and methods, and the phenomena that they study. To begin to devise a framework for organizing studies that have been done on school leadership, including those with a comparative focus, one would need to consider several different issues. These issues include (a) the research orientation or question embedded in the approach, (b) the theoretical model being used to describe leadership (e.g., instructional leadership, transformational leadership, or postmodern), (c) the epistemological frame undergirding the creation of knowledge in the study (e.g., structural-functional, political-conflict, constructivist, poststructural), and (d) the type of methodological approach used in studying the role.

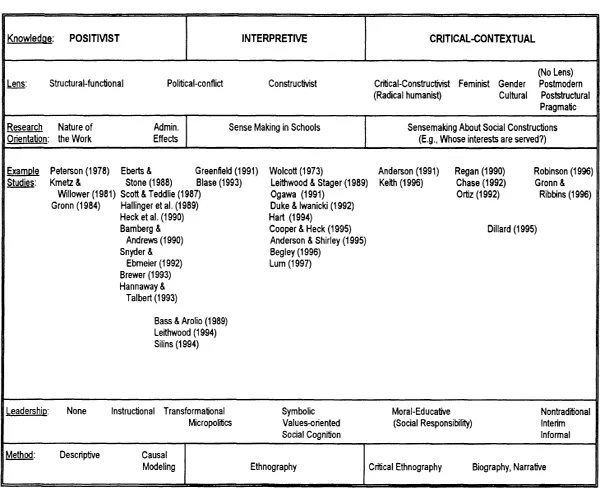

Such a framework should help researchers more clearly understand where they are each working (research orientation, conceptual model, epistemological stance, methodological approach) and what knowledge is being collectively created about school leadership. Recognizing the necessity to reduce what is obviously a complex puzzle of school leadership research, Figure 1 represents an attempt to locate some of the studies discussed in this article according to their broad conceptualizations of knowledge, philosophical frames, research orientation, leadership model, and method. It is hoped that the figure demonstrates the increasing flexibility of perspectives and corresponding methods of investigation being used to study school leadership presently. Although certainly not inclusive, it is intended merely as a preliminary “road map” to the more specific discussion of several approaches to the study of school leadership that follows. The various research aspects comprising the figure are further discussed in the following sections.

Figure 1. Framework of approaches for studying school leadership.

Of course, any research study comprises a variety of these components, including philosophical and theoretical assumptions, research design and questions, and methods of data collection and analysis (Jacob, 1992). For example, the term qualitative has been loosely applied to each of the various levels—research that is interpretative at an epistemological level, more open ended in terms of data collection, or that involves grounded theory (theory arising from the data) in the analysis of the data. Moreover, researchers can collect qualitative data, but their orientations and analyses are more toward a positivist view (Jacob, 1992; Wolcott, 1992).

Defining Leadership

Epistemological Stances Toward Knowledge

Leadership across cultural settings can be studied from a variety of epistemological frames and with both qualitative and quantitative methods. In part, this may have been because the research orientation was directed toward assessing the impact of school leadership on other school processes and, ultimately, on school effectiveness and improvement. Yet, it has also left unanswered many aspects about how leadership is constructed by participants within the schooling context. In this section, several frames and their resulting orientations toward the definition and study of school leadership are explored.

Broadly speaking, positivist, interpretive (or phenomenological), and socially critical (and emancipatory) theories of k...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Editors’ Introduction

- Can Education Values Be Borrowed? Looking Into Cultural Differences

- Mapping the Conceptual Terrain of Leadership: A Critical Point of Departure for Cross-Cultural Studies

- Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Investigating Principal Leadership Across Cultures

- Valuing Differences: Strategies for Dealing With the Tensions of Educational Leadership in a Global Society

- Culture and Moral Leadership in Education

- Unseen Forces: The Impact of Social Culture on School Leadership