eBook - ePub

Organizational Pathology

Life and Death of Organizations

- 187 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Organizational Pathology draws an extended metaphor that the life cycle of an organization is akin to the biological life cycle. Like all living things, organizations will encounter problems that lead to decline and eventual failure. This work discusses the basic problems and life threatening diseases responsible for organizations' failure and death, including organizational politics, organizational corruption, and organizational crime. The book also contains a critical look at crises and fixations; failure and survival; and processes of disbandment and closure of dying organizations.The consideration of these issues follows a diagnostic model of failure. Yitzhak Samuel argues that if the problems that lead to failure can be predicted or diagnosed early, their severity can be assessed and possible remedies can be implemented to avoid escalating crises. At the very least, an understanding of why and how decline happens can be gained from this analysis. This book offers facts about the causes and consequences of organizational downfall and clues about diagnoses of certain symptoms of abnormal behavior, and how to identify early signs of decline or failure. In order to illustrate these abstract arguments and concepts, Samuel uses various real-life examples of events that have occurred in cross-country contexts. In this way, Organizational Pathology: Life and Death of Organizations should serve a variety of readers.Although primarily intended for students and scholars in the social and behavioral sciences who are familiar with the study and the practice of organizations, this book's informal style makes it easily accessible to a wide range of readers. Just as Samuel's previous book on organizational politics led to new lines of research and theory, this book will encourage similar studies in organizational pathology and institutional malaise.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organizational Pathology by Nicos P. Mouzelis,Yitzhak Samuel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Theoretical Framework

Social scientists are well aware of the fact that a considerable proportion of organizations disappear eventually. Many of them come to an end while they are still young. An enormous number of businesses fail and go bankrupt every year in the USA, Europe, Asia, and elsewhere. In one way or another, many large-scale airlines, high-technology enterprises, publishing houses, and retail chains have become extinct during the last several years. The global financial crisis of the present time demonstrates how giant financial institutions, industrial corporations and global businesses can collapse one after the other like a house of cards.

Likewise, all over the world, numerous non-profit organizations often dissolve (e.g., trade unions, political parties). Plenty of them simply fade out, barely leaving a trace behind. Even governmental agencies and state owned corporations are not immune. Many are privatized and transformed into business companies (e.g., defense industries). A huge number of organizations are compelled to downsize repeatedly. All of these events indicate that the life expectancy of organizations tends to be rather short.

The topic of organizations’ success appears to draw more scholarly interest than does the subject of their failure. There seem to be many publications that address the issue of organizational growth than that of organizational decline. This suggests that the notion of organizational birth is more popular in the literature on organizations than that of organizational death.

It is not surprising that positive consequences are usually more appealing for discussion than negative ones. Practitioners prefer to look for strategies and tactics that can make organizations more effective, adaptive, and competitive. Failures tend to be disregarded, as if they were fatal misfortunes that could not be prevented, and therefore are abandoned without further examination.

Nonetheless, gradually the issues of decline, failure, and death are being incorporated into the literature on organization and management (e.g., Argenti, 1976; Whetten, 1988; Guy, 1989; Weitzel and Jonsson, 1989; Meyer and Zucker, 1989; Anheier, 1999; Mellahi and Wilkinson, 2004).

This volume focuses on several pathological aspects of organizations, such as malfunctions, deficiencies, and disorders, which lead to the quietus of organizations as live entities. In an attempt to discuss the conditions under which organizations go out of business, this study examines states and processes that are likened to mortal diseases in biology and to disorders in psychology. In other words, the book is devoted to the exploration of organizational pathologies and the likelihood of death.

Deficiencies and malfunctions, which endanger the strength and survival of organizations, are treated here as pathologies. Organizational crime, corruption, and other related phenomena are similarly dealt with in this context, as representing abnormalities that threaten the existence of organizations. Some scholars argue that for organizations, politics are a normal part of life (e.g., Clegg, 1996); on the other hand, others consider politics to be detrimental to the wellbeing of organizations (e.g., Mintzberg, 1983). In this volume, the perils of politics are discussed. Once these and similar concepts are viewed as pathological conditions and manifestations, it becomes necessary to analyze them within a proper framework.

One may wonder why it is necessary to pay any attention to such fatal problems, which represent the dark side of organizations, or to deal with unpleasant issues such as these. According to the law of entropy, all systems are doomed to fall apart eventually; organizations are no exception. Therefore, scientists and practitioners alike should endeavor to make the most of organizations while they are alive and avoid the dead ones. However, there is another outlook that views organizational pathologies as natural events, which should by no means be ignored.

Evidently, no one casts doubt on the indispensable contribution of pathology to medical research and practice. Similarly, the knowledge acquired through the study of pathology in psychology is essential for understanding and treating mental disorders. In the present view, then, organizational pathology should have a similar role in the study of organizations.

Acquiring a better understanding of the causes and consequences of organizational deficiencies, malfunctions, decline processes, and internal abnormalities may help us predict such problems in advance, assess their severity, apply proper remedies to the extent they are available, avoid the escalation of crisis situations, and postpone the final demise of failing organizations by means of turnaround plans.

The ecological study of organizations sets out to explain birth and death rates in large-scale populations from a historical perspective. In contrast, the study of organizational pathologies focuses on a single organization or on small samples in an attempt to unfold the sequence of fatal problems, not unlike the study of disease etiology in medicine. The ecological approach looks for contextual and external predictive variables, such as the organizations’ age, size, industry, and ownership; the pathological approach, which seeks explanatory variables, considers factors such as leadership and management, strategy, structure, and culture. These two perspectives and their empirical findings are discussed in this volume as complementary elements.

Organizations are perceived here as if they were natural systems, while it is acknowledged that they are not really so. “Organizations [as natural systems] are collectivities whose participants share a common interest in the survival of the system and who engage in collective activities, informally structured, to secure this end” (Scott, 1992:25).

From this vantage point, organizations are regarded as live organisms, whose structure and behavior are mostly determined by their need to survive. Organizations accordingly undergo various changes to cope with the constraints of their environments, as do living organisms in nature. While we follow this line of thought, we should bear in mind that organizations are by no means biological systems of any kind; therefore, this analogy should not be carried too far.

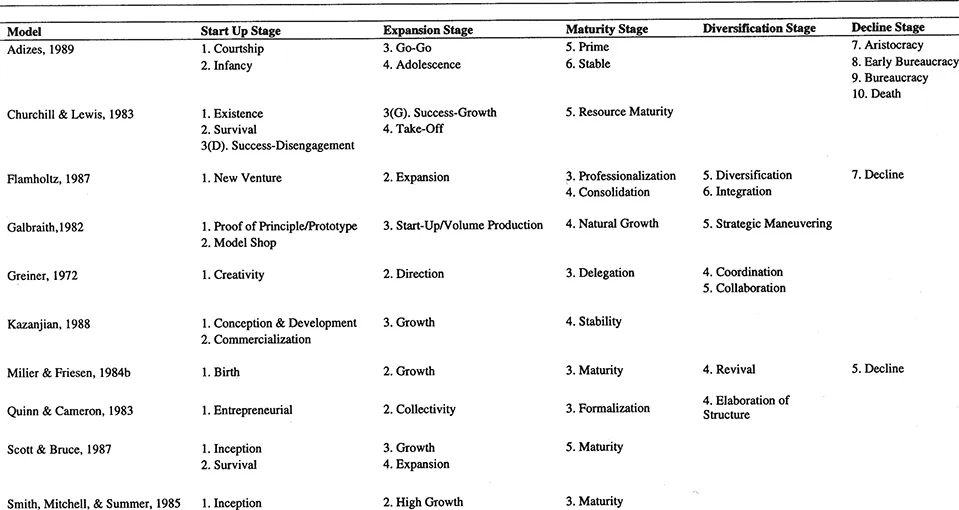

The image of organizations as natural systems has led some scholars to develop the so-called life-cycle paradigm (e.g., Chandler, 1962; Greiner, 1972; Adizes, 1979; Block and Galbraith, 1982; Churchill and Lewis, 1983; Quinn and Cameron, 1983; Miller and Friesen, 1984; Block and MacMillan, 1985; Kazanjian, 1988; Kazanjian and Drazin, 1989; Hanks, 1990). “Traditionally, scholars have used a biological analog to explain the growth patterns of organizations” (Kazanjian, 1998:257). Accordingly, the literature on the organizational life cycle claims that organizations develop through certain stages of maturation, which manifest in a stepwise process: from the first stage, birth, to the last stage, death. In each life-cycle stage, the organization displays a unique set of typical features (Adizes, 1988). A life-cycle stage is defined as “a unique configuration of variables related to the organization’s context and structure” (Hanks, Watson, Jansen, and Chandler, 1994:7). Proponents of this paradigm generally agree that organizations evolve in stages, but they disagree about the number and the nature of these life stages.

The life-cycle model rests on the assumption that living organisms, organizations, as well other open systems are all subject to a life-cycle destiny. They are born, grow, mature, age, and eventually die. The sequential changes that occur in organizations represent evolutionary stages; in other words, the process is similar to the biological life cycle found in nature (Daft, 2004).

The life-cycle paradigm is well established in the literature. Although not accepted by all, it is widely discussed (see, for example, Whetten, 1987). The findings presented in the relevant literature indicate that organizations evolve in a consistent and predictable manner. They move from one stage to the next, by making appropriate changes in their structure and function. These structural transformations enable them to cope with problems entailed in the process of growth. Typically, this process in organizations involves a great deal of pain, sometimes even severe crises (Greiner, 1972).

Students of organizations portray different models of the organizational life cycle, describing stages of growth and development. They emphasize the unique set of characteristics that typifies each stage. More important than the different number of stages that each model presents is the fact that these stages (1) are sequential, (2) follow a hierarchical progression, and (3) involve a range of organizational activities and structures (Quinn and Cameron, 1983). Table 1.1 compares various models of organizational life-cycle proposed in the literature.

Once organizations are treated as natural systems, they are presumably bound to meet their end at one time or another; this is obviously the last stage of their life cycle. Organizations as systems are subject to the second law of thermodynamics—“the law of entropy” (Katz and Kahn, 1978; Scott, 1992). Yet, regardless of whether all organizations must die, it is quite likely that most of those that do reach their demise do so “unnaturally,” due to incurable conditions. Borrowing from the medical language, such a condition is called an organizational pathology. Pathology is usually defined as “an abnormal condition or biological state in which proper functioning is prevented” (Reber, 1985:521). The concept also serves as a general label for the scientific study of such conditions. Keeping to this language, the following chapters address the pathogenesis of organizational death, namely, they discuss the mechanisms by which certain factors give rise to various terminal diseases.

Table 1.1 Comparison of Life-Cycle Stage Models: Names and Numbers of Stages

Source: Hanks, S. H., Watson, C. J., Jansen, E. and G. N. Chandler. “Tightening the Life-Cycle Construct: A Taxonomic Study of Growth Stage Configurations in High-Technology Organizations.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 1993 (Winter), Vol. 17 (5). Reproduced with the permission of Blackwell Publishing.

Similar to individuals, organizations may suffer prolonged, severe pathologies that do not necessarily lead to death. One such type of pathology is known in medicine as chronic disease. In organizations, the equivalent of chronic disease takes the form of an enduring deficiency in the production or the support subsystems. Despite these problems, long-lasting organizations find ways to adapt to these deficiencies and to go on with their tasks. They bypass chronic conditions by concealing them from the public gaze and by adjusting the budget and workforce allocated to the deficient subsystems. For example, “when management’s goal is to maximize achievement of the organization’s mission, it is practical to remove resources from the unit failing to contribute to the effort and reallocate to those units which do” (Guy, 1989:16).

Where there are inherent defects, an organization cannot completely heal. The challenge before management in such cases is to contain the problem within bearable limits. The problematic component is separated as much as possible from the mainstream, to minimize its counterproductive effects. That is the well-known strategy of loose coupling (Orton and Weick, 1990). In some cases, the “sick organ” is wholly excised from the organization’s “body,” by its termination or by selling it off.

Another analogy that can be used in this context of non-terminal pathologies is based on the phenomena of personality disorders in the realm of psychology. Individuals who suffer from such disorders usually are capable of maintaining their routine life, communicating with family members and friends, and performing various tasks. The seemingly normal life may continue for many years, although it carries a great deal of hidden pain, functional difficulties, and recurring anxieties. Organizations’ participants may display behavior patterns that are analogous to symptoms of personality disorder. Some examples of such pathologies are doing things only “by the book;” following superiors’ instructions at the expense of clients’ needs and against the public interest; and stubborn resistance to change—even when it is, admittedly, much needed (Scott, 1992).

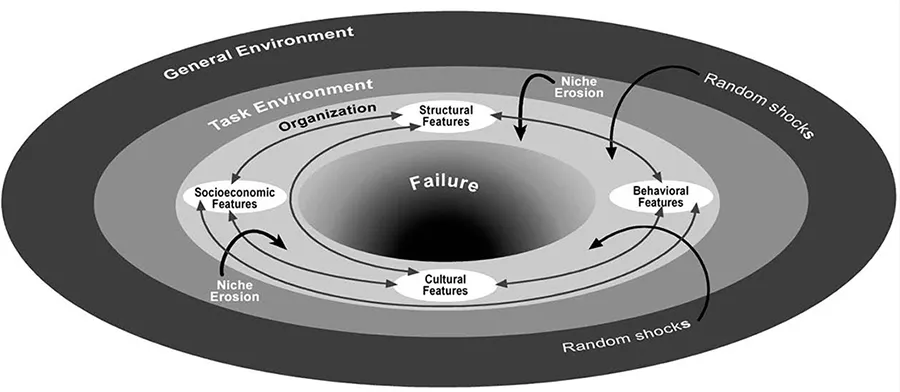

This point in the introduction is an appropriate place to present the author’s theoretical framework that guides this volume. It is portrayed graphically in Figure 1.1.

As a point of departure, it is assumed here that two sets of factors make a considerable impact on organizations’ chances of survival. These factors are internal and external. The former reside within the organization itself, and are designated in the literature as r-extinction; the latter reside in the organization’s environment, and are designated in the literature as k-extinction.

Figure 1.1

A Diagnostic Framework of Organizational Failure

Organizations should be conceptualized as open systems. As such, they are embedded in economic, political, social, and technological environments simultaneously. While organizational environments have been classified in many ways, in the present context they are broadly classified according to only two main groups: the task environment and the general environment. The task environment is that with which the organization interacts directly. “The task environment typically includes the industry, raw materials, and market sectors, and perhaps the human resources and the international sectors.” The general environment includes “those sectors that might not have direct impact on the daily operations of a firm but will indirectly influence it. The general environment often includes the government, socio-cultural, economic conditions, technology and financial resources sectors” (Daft, 2004:137-8).

The task environment of organizations consists of various market niches (e.g., fast food, daily newspapers, fancy cars, etc.) in which a certain population of organizations makes its living. An organizational niche, then, contains a certain combination of various resources (e.g., raw materials, human resources) that carry those organizations and enable them to survive. Depletion of the niche resources jeopardizes the survival chances of those organizations. In fact, such niche erosion affects both birth and death rates of organizations. Organizations are likely to fail whenever their particular niche can no longer carry them, for whatever reason.

The general environment is usually more remote than the task environment, but influential nevertheless. The general environment affects organizations’ chances of survival by virtue of the “random shocks” it may deliver: large-scale external crises of various kinds, such as a sudden war, a coup, some natural disaster, or an economic crash. Although such random shocks impinge upon organizations indirectly, they serve as trigger effects, which bring some organizations to a state of bankruptcy, breakdown, or quick collapse. Even the survivors are vulnerable to loss of clientele, shortage of supplies, and shrinkage of their profits. Hence, many suffer from serious problems.

As Figure 1.1 suggests, the wellbeing and survival of organizations presumably depend on the following internal factors: structure, culture, social-economic conditions, and behavioral patterns. Each one of these consists of a set of organizational features representing one dimension of the organization. Taken together, these dimensions enable us to define and diagnose the state of affairs that characterizes a given organization at a given time. Note that the posited relationships between these dimensions represent systemic causal loops, which reinforce one another reciprocally.

Briefly, the structural dimension of organizations represents features such as functional differentiation, centralization, formalization, and hierarchization of the organization.

The socioeconomic dimension of organizations consists of parameters reflecting their social strength in terms of quantity and quality of the human resource (e.g., size of the work force and its level of education). It also indicates the economic vigor of organizations (e.g., assets, investments, and slack resources). In addition, this complex dimension indicates organizations’ market position (e.g., market share, sales volume, and backlog of orders).

The cultural dimension of organizations represents basic assumptions (e.g., the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. A Theoretical Framework

- 2. Organizational Fatality

- 3. Failure Prediction Models

- 4. Maladies and Disorders

- 5. The Spiral of Decline

- 6. The Perils of Politics

- 7. Greed and Corruption

- 8. Corporate Crime

- 9. Crises and Fixations

- 10. Failing and Surviving

- 11. Disbandment and Closure

- 12. Lessons Learned

- References

- Index