- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

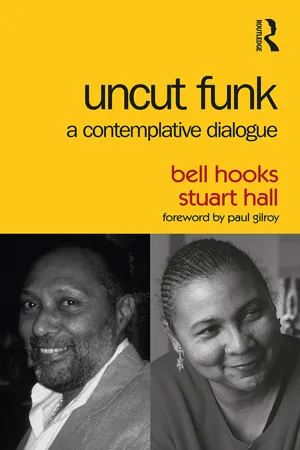

About this book

In an awesome meeting of minds, cultural theorists Stuart Hall and bell hooks met for a series of wide-ranging conversations on what Hall sums up as "life, love, death, sex." From the trivial to the profound, across boundaries of age, sexualities and genders, hooks and Hall dissect topics and themes of continual contemporary relevance, including feminism, home and homecoming, class, black masculinity, family, politics, relationships, and teaching. In their fluid and honest dialogue they push and pull each other as well as the reader, and the result is a book that speaks to the power of conversation as a place of critical pedagogy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Uncut Funk by bell hooks,Stuart Hall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Dialogue between bell hooks and Stuart Hall

bell: For me, conversation is a place of learning. I love a good conversation. It’s something I live for, one of the real pleasures of life, and yet, I find as I grow older it is more difficult to have a good conversation.

Stuart: Conversation matters to me a lot, too, although, I don’t always say I live for conversation. I live for narrative. Of course, conversation is a lot about narrative, but there are many other kinds of conversations. I find that the conversations that I quite like are those where people are telling me stories about themselves, where there is an element of the confessional. I like to have narrative rehearsed. I like everyday conversation. For instance, my son comes in, and he is terribly tired. He has just been making a film about Brixton. He was there with Mandela. I haven’t seen him in a week, and I say, “How’s it going?” He says, “Ahh, I’m definitely tired. I don’t know if I can bring myself to talk about this.” How do you read this when you’re hungry for narrative? When I go home in the evening, I want Catherine to tell me about her day, who phoned, and what were the small things that have made up her day. I am not only interested in the big things of life. Perhaps this is different than conversation.

bell: I believe that is conversation. Conversation has a polyphonic variety. You can move in it from the mundane to the profound. It ranges from lessons to be learned about the mundane to something that is deeper and more exciting. I have been thinking about growing up in a world of folks who never learned how to read or write, or folks who didn’t read much, an intense world of non-readers and non-writers. What I remember most about that world is this passion of conversation. Just as you are pointing out, there were always extensive narratives about the weather. My grandparents would rise at the crack of dawn, they would turn on the radio, then carry on these conversations which involved talking back to the radio, talking to each other, and talking about the upcoming day.

Stuart: Now as you say that, I am reminded of a childhood memory which I hadn’t thought about before. I lived with my family in Kingston. For a lot of reasons, we were the advanced, modern folks who had gone to the big city. My father worked in an electric company, and my mother was intent on status and going up in the world. I found this, for various reasons, a very forbidding place in which to grow up. The place I loved going to was my father’s place in the country, in Old Harbour, which is outside of Kingston. It’s not very beautiful. It’s on the south side of Jamaica which is the flat, dry side, not the romantic northern coast. It is not a tourist area. It is just a little, dusty, country town. They had this very pretty, not quite gingerbread, but almost gingerbread, very small home. It was my grandmother’s home (my father’s mother), who I am very much like. The house was full of aunts, because my father and his brother got married and moved away. Of the five aunts only one got married and left. This was a house of unmarried but strong and varied women. They were all different from one another. My aunt, who was a teacher, died last year at 105. She was teaching on her back verandah at age 102. My favorite aunt was Post Mistress.

I loved to go to Old Harbour at Christmas. I remember that I didn’t enjoy Christmas day which we celebrated in Kingston. It was for fashionable folks. But then on Boxing Day we would go to Old Harbour. It was a country Christmas, but I just thought it was wonderful. The best moment was after Christmas dinner when, as a child, I would go and lay down on this big bed and listen to the aunts talking with my mother about the village gossip. I thought it was just wonderful. Even though I didn’t know the people they spoke of I really thought this was just wonderful. It was like a continually unrolling serial. Until now, I hadn’t thought about how those moments mark a space where I learned to love people telling me about their everyday life in conversation. It makes sense because that place was a very powerful repository of positive things. It is a positive pole in my childhood. All the negative things circle around my own family’s home while the positive circles around my aunts’ and my grandmother’s home.

I loved to go to Old Harbour at Christmas. I remember that I didn’t enjoy Christmas day which we celebrated in Kingston. It was for fashionable folks. But then on Boxing Day we would go to Old Harbour. It was a country Christmas, but I just thought it was wonderful. The best moment was after Christmas dinner when, as a child, I would go and lay down on this big bed and listen to the aunts talking with my mother about the village gossip. I thought it was just wonderful. Even though I didn’t know the people they spoke of I really thought this was just wonderful. It was like a continually unrolling serial. Until now, I hadn’t thought about how those moments mark a space where I learned to love people telling me about their everyday life in conversation. It makes sense because that place was a very powerful repository of positive things. It is a positive pole in my childhood. All the negative things circle around my own family’s home while the positive circles around my aunts’ and my grandmother’s home.

bell: You just made me think of how we always say it is a dangerous thing in our house to say anything. For instance, in our little, tiny house, after we eat everyone lays out on different beds to rest, but they are also listening. So from any different corner or room you might get feedback when you thought that you were just talking to one other person. Everyone feels that if you have something that you really want to keep private—

Stuart: You’re best not to say it!

bell: Yes, and as a country girl I went away to college thinking that college was going to be this place for these kinds of conversations. It was as if I thought that college was going to replace the discussions of our little town and our neighborhoods with ideas, but that we were still going to be rising early in the morning to sit and to chat. I remember the lack of spaces of conversation as one of my deepest disappointments when I arrived at Stanford. Evidently, at one time, they had designated rooms where people could get together to have tea and talk.

Stuart: Yes, and when you arrived they were no longer used in that way. I don’t know that I knew enough about college even to imagine it.

bell: It was because I didn’t know what it was like that I was imagining it.

Stuart: Yes. I must say, not all the time, but many of the years I spent at Oxford, and I was there a long time, six years, were times of extreme and intense intellectual and political conversation. It was where the New Left started, and all of those people were around. We had a big student house where people lived, and it was always full of a cross section of people of the Caribbean, people from the Left, people studying literature, people in art school, not just people from the university. It was a place of very, very intense variety, and intense conversation. If I had gone with the expectation for conversation, it was in a way met.

bell: Do you think this had to do with the times?

Stuart: Yes, this was the late fifties and the sixties. I don’t want to be too romantic about it either, because there were other things that I absolutely hated about it. I didn’t want to go to Oxford, and I hated it by the time I left, so I don’t want to paint it in a rosy glow. However, this place was where Universities and Left Review was first started, and it was where I made an independent life for the first time. I left home and went to college where they looked after you for a year. Then I moved out into a student house where we made an alternative center—a radical, political, literary center—and battled against official Oxford and all it stood for. All of this gave it an intellectual intensity. It was really very exciting.

bell: As someone who came from a working, poor environment to Stanford, I always had to work while attending school to earn money for books and living expenses. This put me in a space of “would be” young intellectual in the everyday work setting, and one of the ways that I dealt with that setting was to have conversations. I could be sitting as a telephone operator at my microphone all day, and in the meantime galvanizing everybody into a certain kind of conversation about our lives. When I started writing Ain’t I a Woman? I was working at the telephone company and talking with all of these women who worked there about their perceptions of black womanhood. That was a real important space. It’s because of these experiences that I felt conversation is a place of potential pedagogy. When people are seated together at lunch time, whether you’re from a different class or not, there is a possibility of sharing in conversation.

Stuart: Yes, sharing across those boundaries. One of the nice things about conversation, as opposed to conferences and fixed formalized occasions, is, of course, its fluidity. It can move from the trivial to the profound, in and out, across boundaries of sexualities and genders, boundaries of experience. It gives you a sense of the dialogic, of conversation as exchange.

bell: The other day a black, Southern, male plumber came to my house, and I was saying to him, “I can’t keep my tub clean!” He said, “Do you have some cleanser?”, and I said, “Oh, I’ve tried cleanser.” Then I brought him the cleanser that he demanded. He cleaned a little circle, and then said, “Ah, this is a trick. This is just about getting me to clean your tub.” We then began a conversation about gender and roles.

Stuart: Which you couldn’t have done any other way. If you had proposed it as a formal topic of exchange it wouldn’t have got off the ground.

bell: I was going to lunch with Anthony Appiah that day so I was saying to him that I had to get out of there and go to lunch. He asked me, “Who are you going to lunch with, the man in your life?” I said, “Actually I’m going to lunch with a gay, male friend.” He then told me to scratch that, and that he was married, but that he could be “my special friend.” That started another whole conversation about living in the Village, and what gayness means in terms of friendship. This has been something that has continually intrigued me as a thinker, the possibility of engaging knowledge across different kinds of boundaries. I have been somewhat saddened by the fact that my life became more centered around institutions—the university has become harder for me to have certain kinds of conversations. I have been thinking about the way the act of praying for talk on the formal lecture circuit is so negating of conversation. Being paid to talk, to lecture has brought to the very act of talking about ideas a spirit of violation, so that the joy of conversing is denied.

Stuart: I was saying before that the fifties and sixties facilitated certain kinds of conversations, but I also think that it may have to do with one’s stage in life. I don’t know that I have many conversations like that. There is a limited range of people with whom I have those sorts of conversations with now. This may have to do with what you were talking about earlier, that teaching, being paid to teach, is a way of being paid to talk, and so the status of talk is changed by that fact.

bell: I was thinking about the conditions under which Cornel West and I did Breaking Bread. I remember that we would meet in New York or he would come to Oberlin, Ohio at different times. There we would actually walk around this little town of cornfields and sing songs to each other, sit with our whiskey in the night, and I can’t imagine doing that with him now. I hardly see him. When we talk it’s talk on the run, not that talk amidst languorous times. I remember that there were several estate sales that we stopped to look at, and I think about how all of those things changed the nature of how we talked about ideas.

Stuart: It is as much about rhythm as anything else. If you are living the rest of your life at a certain intensified rhythm, it just doesn’t fit the rhythm of conversation. You can’t hurry. There has to be a certain space around conversation to allow it to either come or go, to last a short time or a long time, or to organize around established chunks.

bell: My early books were thought through in conversation, because I was in that liminal space between academy and a work world. When I was writing Ain’t I A Woman and working 40 hours a week at the phone company there was this sense that if I had an idea that was the place I could go to test it out. There could be this ongoing conversation, and my sense of the book actually emerged as I talked it through with other people, and not as an internal, silent dialogue with myself.

Stuart: I don’t think about writing like that. I think about thinking like that. So in that sense, I always, over any sustained period, work best intellectually with a group of people that is involved, and therefore, constantly talking in one form or another over our ideas. Writing is for me a much more isolated thing, but that is not to say that there isn’t a conscious adoption of what might be called the conversational voice. In my writing I am more aware of speaking what I am saying than of writing it. When I write only, I write in a very clotted way, but as soon as I think about writing as I would speak it, I write in a much more accessible, vernacular way. There is a trace of conversation in spite of the fact that it hasn’t actually come out of talking with others.

bell: A lot of people have characterized my work as having that conversational element, and in my case that is precisely right, because it does come out of daily conversations. I just finished a new book of essays on film and one of the essays came from going with a friend to see Pulp Fiction. We left the theater at midnight. After an intense, impassioned conversation about the movie, I went home, I wrote all night long. I wanted the writing to have the freshness and intensity of that conversation. If too much time goes by between my seeing a film, talking about it and then I’m not able to bring that intensity to the writing.

Stuart: I don’t think of writing like that. For instance, I don’t like to talk about films immediately after I see them. I get annoyed with people who instantly want to tell me what it’s like. I want the film, the images to settle. In this sense, writing is for me an internal conversation. This is not to say that it doesn’t make me look at it in restrospect, to see the trace of all those conversations that have happened before and come back into the writing. I don’t think of writing as capturing conversation.

Conversation has to do with people. It is partly related to friendships and who one has around one. Here I am strangely placed, because I am out of my generation. The people I feel closest to now, whom I have conversations with, are a different generation from the generation I grew up in. I’ve left the generation I grew up with emotionally, and certainly intellectually and politically. I feel I was reborn in another time. It really is quite strange to discover that people can no longer imagine how old you are. I see this when I say that I have been around a very long time, and people often ask if I am from the sixties. I tell them, “No, the fifties!” I had very intense relationships with people in the fifties. They were older than I was which takes me back further. These were people born after the war in the forties, and that whole generation has not been present to me for about twenty to twenty-five years. This means that the people I am in conversation with are much younger than me, and it is not just a question of age, but more that their experience is very different. That is what I want. I am not complaining, but it does alter the nature of the conversation. The conversation is more like teaching. It has that character of the older person and the student, although they’re teaching, and I’m learning.

Conversation has to do with people. It is partly related to friendships and who one has around one. Here I am strangely placed, because I am out of my generation. The people I feel closest to now, whom I have conversations with, are a different generation from the generation I grew up in. I’ve left the generation I grew up with emotionally, and certainly intellectually and politically. I feel I was reborn in another time. It really is quite strange to discover that people can no longer imagine how old you are. I see this when I say that I have been around a very long time, and people often ask if I am from the sixties. I tell them, “No, the fifties!” I had very intense relationships with people in the fifties. They were older than I was which takes me back further. These were people born after the war in the forties, and that whole generation has not been present to me for about twenty to twenty-five years. This means that the people I am in conversation with are much younger than me, and it is not just a question of age, but more that their experience is very different. That is what I want. I am not complaining, but it does alter the nature of the conversation. The conversation is more like teaching. It has that character of the older person and the student, although they’re teaching, and I’m learning.

bell: We have mentioned to each other many times that it was Paul Gilroy that kept saying to me, “The two of you need to talk.” I kept saying to him, “but you know, I’m intimidated.” I got scared, and you just touched upon why. Normally I am talking to people who are much younger than me or are colleagues and friends my age. Intergenerational dialogues don’t really occur very often. I wonder how much that absence diminishes us. I remember Toni Cade Bambara telling me once that at some point in her life she looked around and found that she was only talking to people that were younger than her. She did not think this was good for her intellectual as well as her emotional development. She felt that she needed to have a range of peers. The fact that she was always dialoguing with younger audiences made her think about the relationship between conversation and power. “How will I talk to Stuart? Will I imagine that I am his peer?” It is interesting to think about the space that allows conversation to happen.

Stuart: I understand how she felt; although, I don’t know that I have felt it myself in that way. I don’t know that I could do anything about the constancy of intergenerational conversation in my life because of two transitions in my life. One is coming to England at the end of my youth, the beginning of my adulthood, and this does mean that there is already one generation that I have lost, the generation I was schooled with, the generation of my teenage life. All of that is lost. I don’t mean that I don’t know them. I see them when I go back to Jamaica, but their experience in the sixties and seventies was so profound, and so profoundly different than mine, which was also profound. It is two different experiences. They are not my interlocutors anymore. Thinking back that is one direction it went, and then there is another one, which is the one that I found when I came here, which I talked about, the one at the university involved in the New Left. I made a huge shift from that at some point in the sixties. At some point in the sixties I became again a very different person. Again, those people I know and know very well, and some of those people I still feel very close to, but some of them I don’t feel that close to and haven’t for quite a long time. I feel that with some of them I couldn’t even have a conversation now, because they haven’t a clue as to who I am.

bell: I have felt that most deeply within the feminist movement. I have continued to try to stretch myself while a lot of the people that I initially started out talking with in the early seventies haven’t continued to want to stretch the meaning of feminism, the boundaries of feminism. In fact, there is a movement away from that stretching. The leap into cultural studies happened as a way to save myself from that static momentum, that conversation that had somewhat stopped.

Stuart: Unlike you when I talk about a political generation I am talking about a political generation t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- foreword

- preface

- dialogue between bell hooks and Stuart Hall