eBook - ePub

Beyond Malthus

The Nineteen Dimensions of the Population Challenge

- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Beyond Malthus

The Nineteen Dimensions of the Population Challenge

About this book

On the bicentennial of Malthus' legendary essay on the tendency of population to grow more rapidly than the food supply, this book examines the impacts of population growth on 19 global resources and services, including food, fresh water, fisheries, jobs, education, income and health. Despite current hype of a 'birth dearth' in parts of Europe and Japan, the fact remains that human numbers are projected to increase by over 3 billion by 2050. Populations in rapidly growing nations are in danger of outstripping the carrying capacity of their natural support systems and governments in such situations will find it increasingly hard to respond to crises such as AIDS, food and water shortages and mass unemployment. Beyond Malthus examines methods such as the expansion of international family planning, investment in educating young people in the developing world and promotion of a shift towards smaller families which will represent the most humane response to the possible ravages of the population explosion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Beyond Malthus by Lester R. Brown,Gary Gardner,Brian Halweil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Population Challenge

During the last half-century, world population has more than doubled, climbing from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 5.9 billion in 1998. Those of us born before 1950 are members of the first generation to witness a doubling of world population. Stated otherwise, there has been more growth in population since 1950 than during the 4 million preceding years since our early ancestors first stood upright.1

This unprecedented surge in population, combined with rising individual consumption, is pushing our claims on the planet beyond its natural limits. Water tables are falling on every continent as demand exceeds the sustainable yield of aquifers. Our growing appetite for seafood has taken oceanic fisheries to their limits and beyond. Collapsing fisheries tell us we can go no further. The Earth’s temperature is rising, promising changes in climate that we cannot even anticipate. And we have inadvertently launched the greatest extinction of plant and animal species since the dinosaurs disappeared.

Great as the population growth of the last half-century has been, it is far from over. U.N. demographers project an increase over the next half-century of another 2.8 billion people, somewhat fewer than the 3.6 billion added during the half-century now ending. In contrast to the last 50 years, however, all of the 2.8 billion will be added in the developing world, much of which is already densely populated.

Even as we anticipate huge further increases in population, encouraging demographic news seems to surface regularly. Fertility rates, the average number of children born to a woman, have fallen steadily in most countries in recent decades. Twice in the last 10 years the United Nations has moderated its projections of global population growth, first in 1996 and then again in 1998. Unfortunately, part of the latter decline in population projections is due to rising mortality rather than declining fertility.2

In contrast to the projected doublings and triplings for some developing countries, populations are stable or even declining in some 32 industrial nations. Compared with the situation at mid-century, when nearly all signs pointed to galloping population increases for the foreseeable future, today’s demographic picture is decidedly more complex.

Anyone tempted to conclude that population growth is becoming a “non-issue” may find this book a reality check. Despite the many encouraging demographic trends, the need to stabilize global population is as urgent as ever. Although the rate of population growth is slowing, the world is still adding some 80 million people per year. And the number of young people coming of reproductive age—those between 15 and 24 years old—will be far larger during the early part of the next century than ever before. Through their reproductive choices, this group will heavily influence whether population is stabilized sooner rather than later, and with less rather than more suffering.3

In addition, population growth has already surpassed sustainable limits on a number of environmental fronts. From cropland and water availability to climate change and unemployment, population growth exacerbates existing problems, making them more difficult to manage. The intersection of the arrival of a series of environmental limits and a potentially huge expansion in the number of people subject to those limits makes the turn of the century a unique time in world demographic history.

The rate of global population growth has been slowing since the 1960s, when birth rates began to decline in many countries as a result of changing cultural, religious, and socioeconomic cues. As families moved to cities, large numbers of children were no longer needed as agricultural laborers; they became instead an economic burden for families. The increasing reach of radio and television altered the aspirations of billions of people, while rising school enrollment and economic progress exposed young men and women to opportunities beyond family life. Meanwhile, the growing acceptance and availability of family planning afforded couples a viable means to reduce the number of children they chose to have. Taken together, these trends helped lower the growth rate of world population from its peak rate of 2.2 percent in 1963 to 1.3 percent in 1998.4

Although still an issue of global importance, population growth carries greater urgency in some countries than in others. In contrast to mid-century, when populations were growing everywhere, growth rates now vary more widely across countries than at any time in history. Some countries have stabilized their populations while others are expanding at 3 percent or more per year—a rate that yields a 20-fold increase within a century.

Some 32 countries, with 12 percent of the world’s people, have essentially achieved population stability, with growth rates below 0.4 percent per year. With the exception of Japan, all 32 are in Europe, and all are industrial countries. Some of these, including Russia, Japan, and Germany, are actually projected to see population declines over the next half-century.5

In another group of 39 countries, fertility has dropped to replacement level—roughly two children per couple—but populations will continue to grow for several decades because a disproportionately large number of young people are moving into the reproductive age group. Among the countries in this category are China and the United States, the world’s first and third largest countries, which together contain 26 percent of the world’s people.6

At the other end of the spectrum, the high-growth end, seven countries are projected to triple their populations before they stabilize. Another group—59 countries, mostly in Africa—is set to double and in some cases nearly triple their populations by 2050. A third group of developing countries, also 59 in number, fall short of a doubling in the next half-century, though they are still far from population stability.

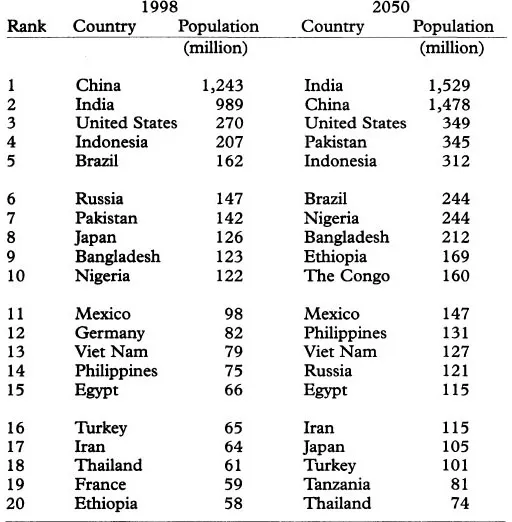

Among the more rapidly growing countries are three large ones facing enormous increases in population in coming decades. (See Table 1-1.) Ethiopia’s current population of 58 million is projected to nearly triple, as it climbs to 169 million in 2050. Pakistan’s population is projected to go from 142 million to 345 million, nearly surpassing that of the United States. Nigeria, meanwhile, is projected to go from 122 million today to 244 million, giving it slightly more people in 2050 than there were in all of Africa in 1950. Given the environmental constraints already facing these countries, especially the growing scarcity of water and cropland, it is unlikely that their projected population increases will actually materialize. The question is whether lower than projected growth will be realized because of societal choices to moderate growth, or because nature ruthlessly imposes its own constraints.

TABLE 1-1. The 20 Largest Countries Ranked According to Population Size, 1998, With Projections to 2050

SOURCE: Population Reference Bureau, “1998 World Population Data Sheet,” wall chart (Washington, DC: June 1998); United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 1998 Revision (New York: December 1998).

Although the rate of world population growth is slowing, far more people are now added to the planet each year—some 80 million—than in 1963, when the growth rate crested. This is because of the momentum inherent in population growth, a momentum that requires decades to exhaust. This illustrates the importance of early action to stabilize population. It also suggests why the reproductive choices of the generation now entering adulthood are so important: the consequences of their choices will be felt for decades to come.

As the global population locomotive hurtles forward—despite pressure applied to the demographic brakes—there are hazards on the tracks ahead. A number of limits to sustainability are being surpassed, or are about to be. This book looks at the consequences of population growth for 19 environmental and social dimensions of the human experience, and concludes that any number of imminent hazards could trigger a demographic train wreck.

In this respect, we are part of a long tradition dating back to 1798 when Thomas Malthus, a British clergyman and intellectual, warned in his “Essay on the Principle of Population” of the check on population growth provided by what he believed were coming constraints on food supplies. Noting that population grows exponentially while food supply grows only arithmetically, Malthus foresaw massive food shortages and famine as an inevitable consequence of population growth.7

Critics of Malthus point out that his pessimistic scenario never unfolded. His supporters believe he was simply ahead of his time. On the bicentennial of Malthus’ legendary essay, and in an era of environmental decline, we find his focus on the connection between resource supply and population growth to be particularly useful. We move beyond Malthus’s focus on food, however, to look at several resources—such as water and forests—whose supply may be insufficient to support projected increases in population. We also examine social phenomena including disease and education, and analyze the effect of population growth on these.

The results of our analysis offer further evidence that we are approaching—and increasingly broaching—any number of natural limits. We know that close to a tenth of world food production relies on the overpumping of groundwater, and that continuing this practice will mean a substantial decline in food production at some point in the future. We know that both atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations and the Earth’s surface temperature are rising. We know that we are the first species in the planet’s history to trigger a mass extinction, and we admit that we do not understand the consequences of such a heavy loss of plant and animal species. In short, we know enough to understand that the growth in our numbers and the scale of our activities is already redirecting the natural course of our planet, and that this new direction will in turn affect us.

The relationship between these natural limits and population growth becomes clear if we contrast key trends projected for the next half-century with those of the last one. For example, since 1950 we have seen a near fivefold growth in the oceanic fish catch and a doubling in the supply of fish per person, but people born today may well see the catch per person cut in half as population grows during their lifetimes. Marine biologists now believe we may have “hit the wall” in oceanic fisheries and that the oceans cannot sustain a catch any larger than today’s.8

Similarly, the finite area that can be cultivated for grain is a worrisome natural limit as population increases. Grainland per person has been shrinking since mid-century, but the drop projected for the next 50 years means the world will have less grainland per person than India has today. Future population growth is likely to reduce this key number in many societies to the point where they will no longer be able to feed themselves. Countries such as Ethiopia, India, Iran, Nigeria, and Pakistan will see grainland per person shrink by 2050 to less than one tenth of a hectare (one fourth of an acre)—far smaller than a typical suburban building lot in the United States.9

Meanwhile, with the amount of fresh water produced each year essentially fixed by nature, population growth shrinks the water available per person and results in severe shortages in some areas. Countries now experiencing this include China and India, as well as scores of smaller ones. As irrigation water is diverted to industrial and residential uses, the resultant water shortages could drop food production per person in many countries below the survival level.

The fast-deteriorating water situation in India was described in July 1998 in one of India’s leading newspapers, the Hindustan Times: “If our population continues to grow as it is now…it is certain that a major part of the country would be in the grip of a severe water famine in 10 to 15 years.” The article goes on to reflect an emerging sense of desperation. “Only a bitter dose of compulsory family planning can save the coming generation from the fast-approaching Malthusian catastrophe.” Among other things, this comment appears to implicitly recognize the emerging conflict between the reproductive rights of the current generation and the survival rights of the next generation.10

As difficult as it is to imagine the addition of another 2.8 billion people to the world’s population, it is even harder to grasp the effects of the rising affluence of a growing population. As we look back over the last half-century, we see that world fuelwood use doubled, paper use increased nearly sixfold, grain consumption nearly tripled, water use tripled, and fossil fuel burning increased some fourfold.11

The relative contribution of population growth and rising affluence to the growth in demand for various resources varies widely. With fuelwood use, most of the doubled use is accounted for by population growth. With paper, in contrast, rising affluence is primarily responsible for the growth in use. For grain, population accounts for most of the growt...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- 1. The Population Challenge

- I. Population Growth and ...

- II. Conclusion

- Notes

- Index