Many Americans, especially those living outside congested areas, are probably satisfied with the state of their roads. “Why,” they might ask, “should roads be privatized? Why not leave things as they are, and let our elected representatives take care of our needs?” These are good questions, to which at least three answers can be given.

The Present Unsatisfactory Situation of Road Provision

Costs Associated with Political Control

First, as road systems are outside the market economy, and unresponsive to consumer needs, road systems exhibit the usual “command economy” characteristics of congestion, queuing, deterioration, and waste. For example, travel on the US Interstate Highway system increased by 38 percent from 1991 to 2001, but additional lane mileage on the system grew by only 5 percent—one seventh of the rate of traffic growth. One result was that the mileage considered to be severely congested on the urban portions of the Interstate system increased 31 percent from 1996 to 2001—from 2,342 miles to 3,059 miles (TRIP, 2003).

As pointed out by Semmens in chapter 2, a major cause of the inefficiency is the political control of road systems, which enables road users to shift the costs they impose to other road users, and even to other taxpayers. Farmers in Kansas, for example, pay to rebuild the Wilson Bridge over the Potomac to relieve congestion in Washington D.C. Those who underpay are thus encouraged to increase their road usage at the expense of others, illustrating Bastiat’s insight that government is seen as a device to enable everybody to live at everybody else’s expense.

Another major cause of waste is the low priority accorded to routine road maintenance because new construction is more popular with politicians. Delays in maintenance can double or triple the costs of subsequent road repair and reconstruction. In the United States, federal grants favor new construction over maintenance. In Sub-Saharan Africa, a third of the main road system was eroded as a result of poor maintenance (Heggie 1995).

The excessive costs of the public ownership of roads are not confined to the management of existing roads. There is little reason to believe that governments will build new roads where they are most needed, as road construction responds to political pressures. The U.S. Congress has a 1914 rule2 prohibiting the funding of specific roads. This must have been waived in 1982, when ten “demonstration projects” (subsequently called “high-priority projects” or “earmarks”) were funded, at a cost of $362 million, to enable members of Congress to reward potential voters at public expense. Twenty-three years later, the “Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users,” enacted in 2005 to authorize additional highway spending, appropriated $24.215 billion for 6,373 “High Priority Projects” selected by House and Senate members.3 Few, if any, of these projects were considered to be of “high priority” in the states concerned.4

Urban highways in Boston illustrate the waste—particularly federally funded waste—in the political provision of roads. Following the establishment of the Federal Interstate Highway Fund in 1956, Boston’s road planners proposed the construction of an elevated “Central Artery” along the waterfront, three stories high, 1.5 miles long, and 100 feet wide. According to MIT Professor Alan Altshuler, who later became state secretary of transportation, this road was conceived as a result of “a highway juggernaut driven by the lure of 90 per cent federal dollars that had nothing to do with the welfare of Greater Boston” (Altshuler 2002). At the time he wrote that,

An effort to accommodate all potential demand by commuters for high capacity into downtown Boston would be outrageously expensive in terms of highway investment dollars, increased transit deficits, social disruption and environmental degradation.

This elevated highway, for which neither Boston nor the state of Massachusetts would have been prepared to pay, was nevertheless built and, as it aged, carried 200,000 vehicles a day and became one of the most congested highways in America. What to do? Local highway planners decided to use federal funding to demolish the elevated highway after replacing it by a tunnel. An additional tunnel was funded to draw more support, and thus was born the “Central Artery/Tunnel” project (popularly knows as “The Big Dig”) initially estimated to cost $3.3 billion. The use of federal funds was led by Speaker of the House of Representatives “Tip” O’Neill (who also represented a Boston district), and was vetoed by President Reagan. The President’s veto was narrowly overridden, due in part to the vote of Senator Sanford of North Carolina, in exchange for support for tobacco subsidies. So the project went ahead, with the cost now estimated to exceed $14.6 billion.

Thus, the availability of outside funding discouraged consideration of market solutions, or even of modest non-market solutions, to the urban congestion problem. This illustrates the point, made in chapter 20 by Samuel, that efficient solutions to the problems of scarcity are more likely in times of shortage than in times of plenty.

Costs Associated with Congestion

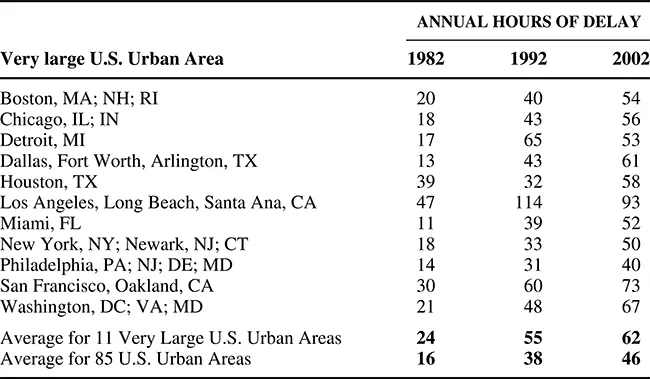

Second, many road users endure excessive traffic congestion in urban areas. The increase in congestion in US urban areas can be seen in the table below:

Table 1.1 Annual Delays per U.S. Motorized Urban Traveler 1982 to 2002

Source: Texas Transportation Institute, “The 2004 Urban Mobility Report,” Table 4.

Traffic congestion is not a new phenomenon. Residents of ancient Rome were kept awake at night by the noise of carts that were excluded from the city in daytime because of congestion.5 Traffic speeds in modern cities range from 40 miles/hour in Sacramento (Cox 2000) through 20 miles/hour in Washington D.C.; 9 to 10 miles/hour in London; 8 miles/hour in Bangkok (Cox 2000); to 6 miles/hour in Manila (Roth/Villoria, chapter 8). This congestion is “excessive” in the sense that, if given the opportunity, many road users would be prepared to pay to travel in less congested conditions.

Congestion occurs when vehicles on the same road network slow each other down, and thus impose costs on one another. For example, an additional vehicle might reduce the average road speed so that other vehicles traveling at the same time and in the same vicinity arrive at their destinations with a thirty seconds delay. Thirty seconds doesn’t sound like much, but if 180 vehicles are delayed and if people value their time at an average of $10 an hour, each vehicle imposes a total cost on others of $15. Because it is imposed on others, this $15 cost is said to be “external.” All vehicles on a road network, not just the latecomers, contribute to congestion. External costs do not enter into a driver’s calculations of when and how much to use a road. As a result, roads tend to be over-used because drivers will use a road whenever their own private benefits exceed their perceived private costs, which are, necessarily, lower than the total costs (private costs plus external costs) resulting from their road use.

In 1924, Frank Knight (Knight 1924) pointed out that if roads were provided by private owners they would not be over-used. Although the costs that the driver of an additional vehicle imposes on others are external to the driver, they are internal to a road owner because such costs reduce the price that the other drivers are willing to pay to use the road. A private road owner, therefore, would allow an additional vehicle on to the road only so long as the price that the drivers were willing to pay exceeded not only their private costs but also the costs imposed on other vehicles. In fact, in a competitive market, prices would tend to just cover all private and congestion costs, so that roads would be neither over- nor under-used.

However, it is possible to envisage a level of “optimum” congestion even in the absence of free markets. When the journey benefits to the user of a road exceed the costs imposed on other road users, the road may be considered under-used, in the sense that benefits to additional users could exceed the additional costs due to them. But when the costs imposed on others exceed the benefits to additional users, the road is overcrowded, and the removal of some traffic could increase its usefulness. If road use could be priced to accurately reflect congestion costs, the optimal economic charge would just equal the costs imposed by vehicles on the rest of the traffic, and the resulting congestion could also be regarded as economically “optimal.” Mohring (chapter 7) and Roth/Villoria (chapter 8) show how to calculate these charges.

Would it be desirable to eliminate congestion entirely? Free markets may offer congestion-free roads to those willing to pay for them, in the same way that private tutors can be hired as an alternative to sending children to school. This would be an expensive solution, but the Long Island Motor Parkway, financed and opened in 1908 by William K. Vanderbilt, was indeed a congestion-free toll road.6 However, in modern large cities eliminating congestion entirely would be impossible without eliminating not only the bulk of existing traffic, but also the much more voluminous potential traffic that would be attracted to a free and uncongested road system.7

Economists associate traffic congestion with under-priced road space and, in the absence of market pricing, are unable to accurately estimate the costs of congestion. Estimates made by Douglass Lee of the Volpe National Transportation Systems Center (Lee 1982), and updated for this volume, concluded that the delays from traffic congestion in 2000 cost about $108 billion, but that the corresponding economic loss is only about $12 billion, because road users would be prepared to accept much of the delay, rather than pay for its elimination.8 Economic pricing of roads in urban areas could, of course, have profound effects on urban travel. It could encourage the use of public transport and, by discouraging long trips, have significant effects on city form and size.

Loss of Personal Freedom

Third, personal freedom is involved. People everywhere strive for mobility to enhance the scope and quality of their activities. Mobility in modern times is increased by the use of cars—trips by public transport typically take twice as long as by car. The use of cars requires roads. In most countries people are allowed to purchase vehicles, but in none can they exercise their powers as consumers to improve the roads they use. Users of freeways in Los Angeles are frequently delayed by congestion, but there is no mechanism available to enable them to buy better service. This is a curtailment of personal freedom, as explained by emeritus London School of Economics professor Alan Day:

If road users are prepared to pay a price for the use of roads that is greater than the cost of providing additional road space (including all the costs, externalities, land costs, a sensible measure of the costs of disturbing any areas with special wildlife and all the other genuine costs which can be identified) then the additional road space should be built. (Day 1998)

In free societies, those in need of goods or services can choose to buy them from appropriate providers. Owners of congested facilities tend to raise their prices, and the resulting potential for increased profits attracts investment to relieve shortages. The application of these principles to roads is illustrated in chapters 7 and 8, which present calculations made for the Twin-Cities (Mohring) and for Manila (Roth/Villoria).

Road congestion and waste may be tolerated without major distress in the wealthy United States, but the poor condition of roads in other countries is a major obstacle to development. In Manila, for example, many people spend four hours each day traveling to and from work. In all countries, with the significant exception of Singapore, congestion and mismanagement coexist with lack of funding for road improvement.