- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Learning to Solve Complex Scientific Problems

About this book

Problem solving is implicit in the very nature of all science, and virtually all scientists are hired, retained, and rewarded for solving problems. Although the need for skilled problem solvers has never been greater, there is a growing disconnect between the need for problem solvers and the educational capacity to prepare them. Learning to Solve Complex Scientific Problems is an immensely useful read offering the insights of cognitive scientists, engineers and science educators who explain methods for helping students solve the complexities of everyday, scientific problems.

Important features of this volume include discussions on:

*how problems are represented by the problem solvers and how perception, attention, memory, and various forms of reasoning impact the management of information and the search for solutions;

*how academics have applied lessons from cognitive science to better prepare students to solve complex scientific problems;

*gender issues in science and engineering classrooms; and

*questions to guide future problem-solving research.

The innovative methods explored in this practical volume will be of significant value to science and engineering educators and researchers, as well as to instructional designers.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralPart I

Cognitive Science Views of Problem Solving

Chapter 1

What Makes Scientific Problems Difficult?

David H. Jonassen

University of Missouri

Prologue: Problems as Cognition and Affect

This chapter and this volume address problem solving from cognitive and scientific perspectives. How do science/technology/engineering/mathematics (STEM) students and workers have to think as they collaborate to solve the myriad scientific problems they experience throughout work and life? The emphases are largely cognitive.

However, problems also elicit affective responses that make problem solving, as a topic, very problematic. These affective responses are important, because (I have discovered that) many professionals, including STEM workers and academics, prefer not to consider or contemplate problems, despite the fact that they are being paid to solve problems. They prefer to, consider problems as opportunities. This aversion to problem solving results, in part I believe, from the affective connotations of the concept “problem.” Thesauri list synonyms of problem, such as dilemma, quandary obstacle, predicament, difficulty, all of which have heavy affective connotations. Indeed, problems often do represent predicaments, and problems are often difficult. However, whether problems represent opportunities or obstacles, they need to be addressed in the research and practice of science in all of its quadrants (Stokes, 2000) because STEM workers are hired, retained, and rewarded for solving problems. Therefore, it is important to STEM educators to better prepare students to seize opportunities or wrestle with dilemmas to solve important scientific problems.

The cognitive perspective on problems, on the other hand, considers a problem as “a question to be solved.” That is the spirit in which this chapter and this volume address problems. STEM students and workers are constantly faced with questions to be solved. They need to learn how to solve them.

What is a Problem?

A problem, from a traditional, information-processing perspective, consists of sets of initial states, goal states, and path constraints (Wood, 1983). The problem is to find a path through the problem space that starts with initial states passing along paths that satisfy the path constraints and ends in the goal state. Unfortunately this conception describes only well-structured problems. For most everyday, ill-structured problems, the goal states and path constraints are often unknown or are open to negotiation, and there are no established routes through path constraints toward the goal state. Information-processing models of problem solving are inadequate for representing the situated, distributed, and social nature of problem solving. As problems become more ill-structured, their solutions become more socially and culturally mediated (Kramer, 1986; Roth & McGinn, 1997). What becomes a problem arises from the interaction of participants, activity, and context.

A problem has two important attributes. First, a problem is a situated unknown, a question to be answered in some context. “Problems become problems when discrepancies are noted, when contradictions are experiences so that at least a temporary state of disequilibrium is reached” (Arlin, 1989, p. 230). Situations vary from algorithmic math problems to vexing and complex social problems, such as environmental sustainability. Second, finding or solving for the unknown must have some social, cultural, or intellectual value. “Problems become problems when there is a ‘felt need’ or difficulty that propels one toward resolution” (Arlin, 1989, p. 230). That is, someone believes that the question is worth answering. If no one perceives a need to answer the question, there is no problem. This latter attribute may expel most formal, in-school problems from the class of real problems because students often do not perceive a need to find the unknowns to problems posed in schools. However, because their teachers do perceive such a need, they are normally regarded as problems.

Problem solving as a process also has two critical attributes. First, problem solving requires the mental representation of the problem in the situation in the world. Human problem solvers construct mental representations of the problem, known as the problem space, the set of symbolic structures (the states of space), and the set of operators over the space (Newell, 1980; Newell & Simon, 1972). Once again, those states of space are easily identifiable in well-structured problems; however, they are much more difficult to identify for ill-structured problems (see chap. 10, this volume). Problem spaces may be externalized as formal models or may be represented using a variety of tools, but it is the mental construction of the problem space that is the most critical for problem solving. Until the problem solver constructs a model of the problem in its context, a viable solution is unlikely. Second, problem solving requires some activity-based manipulation of the problem space. Problem solvers act on the problem space to generate and test hypotheses and solutions.

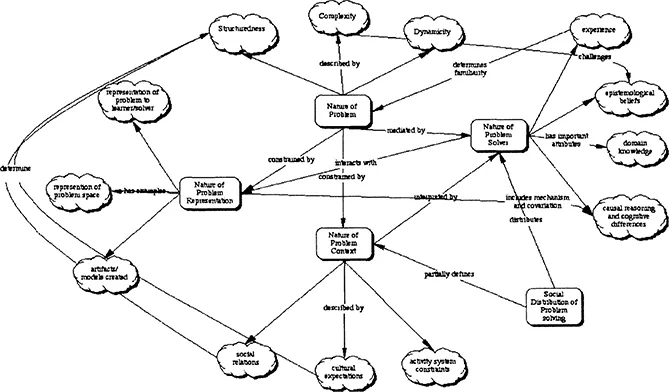

Problems and the methods and strategies used by individuals and groups to solve them, both in the everyday and classroom worlds, vary dramatically. Smith (1991) categorized factors that influence problem solving as external and internal. Internal factors are related to the personal characteristics of the problem solver, such as prior experience, prior knowledge, or strategies used. External factors are those related to the nature of the problem as encountered in the world. Problem solving usually varies both externally (the problem as it exists in the world) and internally. Figure 1.1 depicts internal factors (nature of the problem solver) and external factors (nature of the problem, context, and problem representation) and the attributes of each and the interactions among them. Figure 1.1 provides a graphic organizer of this chapter. I first describe external problem factors and later explicate some internal factors that are important to problem solving.

Figure 1.1. Dimensions of problems.

External Factors

Problems, as they are encountered in the world, differ in several important ways. Bassok (2003) described two important external attributes of problems, abstraction and continuity. Abstraction refers to the representation of the content and context of a problem that either facilitates or impedes analogical transfer of one problem to another. Most classroom problems are more abstract than most everyday problems, which are embedded in various contexts. Continuity of the problem is the degree to which attributes of problems remain the same or change over time (described later as dynamicity). High continuity problems are more easily solved and transferred.

The primary reason for distinguishing among different kinds of problems is the assumption that solving different kinds of problems calls on distinctly different sets of skills (Greeno, 1980). Solving different kinds of problems entails different levels of certainty and risk (Wood, 1983). If solving different kinds of problems requires different sets of skills, then learning to solve different kinds of problems will require different forms of instruction. To better understand how problems differ in terms of required processing, I describe four primary, external characteristics of problems: structuredness and situatedness, contextual factors, complexity, and dynamicity.

External Factor: Structuredness and Situatedness of Problem

The most descriptive dimension of problem solving is structuredness. Problems vary along a continuum form well-structured to ill-structured (Arlin, 1989; Jonassen, 1997; Newell & Simon, 1972). It is important to note that structuredness represents a continuum, not a dichotomous variable. Although well-structured problems tend to be associated with formal education and ill-structured problems tend to occur in the everyday world, that is not necessarily the case. The most commonly encountered problems, especially in formal educational contexts, are well-structured problems. These are typically found at the end of textbook chapters, well-structured problems which present all of the information needed to solve the problems in the problem representation; they require the application of a limited number of regular and circumscribed rules and principles that are organized in a predictive and prescriptive way; and they have knowable, comprehensible solutions where the relations between decision choices and all problem states are known or are probabilistic (Wood, 1983). These problems have also been referred to as transformation problems (Greeno, 1978) that consist of a well-defined initial state, a known goal state, and constrained set of logical operators.

Ill-structured problems, on the other hand, are the kinds of problems that are encountered in everyday life and work, so they are typically emergent and not self-contained. Because they are not constrained by the content domains being studied in classrooms, their solutions are not predictable or convergent. Ill-structured problems usually require the integration of several content domains, that is, they are usually interdisciplinary in nature. Workplace engineering problems, for example, are ill-structured because they possess conflicting goals, multiple solution methods, nonengineering success standards, nonengineering constraints, unanticipated problems, distributed knowledge, collaborative activity systems, and multiple forms of problem representation (Jonassen, Strobel, & Lee, 2006). Ill-structured problems appear ill-defined because one or more of the problem elements are unknown or not known with any degree of confidence (Wood, 1983); they possess multiple solutions, solution paths, or no solutions at all (Kitchner, 1983); they possess multiple criteria for evaluating solutions, so there is uncertainty about which concepts, rules, and principles are necessary for the solution and how they are organized; and they often require learners to make judgments and express personal opinions or beliefs about the problem. Everyday, ill-structured problems are uniquely human interpersonal activities (Meacham & Emont, 1989) because they tend to be relevant to the personal interest of the problem solver who is solving the problem as a means to further ends.

Although information processing theories averred that “in general, the processes used to solve ill-structured problems are the same as those used to solve well structured problems” (Simon, 1978, p. 287), more recent research in situated and everyday problem solving makes clear distinctions between thinking required to solve well-structured problems and ill-structured problems. Allaire and Marsiske (2002) found that measures that predict well-structured problem solving could not predict the quality of solutions to ill-structured, everyday problems among elderly people. “Unlike formal problem solving, practical problem solving cannot be understood solely in terms of problem structure and mental representations” (Scribner, 1986, p. 28), but rather include aspects outside the problem space, such as environmental information or goals of the problem solver. Hong, Jonassen, and McGee (2003) found that solving ill-structured problems in an astronomy simulation called on different skills than well-structured problems, including metacognition and argumentation. Argumentation is a social and communicative activity that is an essential form of reasoning in solving ill-structured, everyday problems. Jonassen and Kwon (2001) showed that communication patterns in teams differed when solving well-structured and ill-structured problems. Finally, groups of students solving ill-structured economics problems produced more extensive arguments than when solving well-structured problems because of the importance of generating and supporting alternative solutions when solving ill-structured problems (Cho & Jonassen, 2002). Clearly more research is needed to substantiate these differences, yet it appears that well-structured and ill-structured problem solving engage different intellectual skills.

The structuredness of problems is significantly related to the situatedness of problems. That is, well-structured problems tend to be more abstract and decontextualized, relying more on defined rules and less on context. On the other hand, ill-structured problems tend to be more embedded in and defined by the everyday or workplace situation, making them more subject to belief systems that are engendered by social, cultural, and organizational drivers in the context (Jonassen, 2000; Meacham & Emont, 1989; Smith, 1991). The role of problem context is described next.

External Factor: Role of Problem Context

In everyday problems that tend to be more ill-structured, context plays a much more significant role in the cognitive activities engaged by the problem (Lave, 1988; Rogoff & Lave, 1984). The context in which problems are embedded becomes a significant part of the problem and necessarily part of its solution (Wood, 1983). Well-structured problems, such as story problems (described later), embed problems in shallow story contexts that have little meaning or relevance to learners. Workplace engineering problems are made more ill-structured because the context often creates unanticipated problems (Jonassen et al, 2006). Very ill-structured problems, such as design problems, are so context-dependent that the problems have no meaning outside the context in which they occur.

The role of context defines the situatedness of problems. Situatedness is concerned with the situation described in the problem (Hegarty, Mayer, & Monk, 1995). Rohlfing, Rehm, and Goecke (2003) defined situatedness as a specific situation in which problem-solving activity occurs, contrasting it with the larger, more stable context that supplies certain patterns of behavior and analysis for situations with which to be confronted. Any situation may be constrained by several, overlapping contexts. That is why everyday problems are often more difficult to solve, yet they are more meaningful. Situativity theorists claim that when ideas are extracted from an authentic context, they lose meaning. The problem solver must accommodate multiple belief systems embedded in different contexts.

External Factor: Complexity

According to Meacham and Emont (1989), problems vary in terms of complexity (how clearly the problem’s initial and goal states are identified). Complexity is an interaction between internal and external factors. Problem-solving complexity is a function of how the problem solver interacts with the problem, determined by the difficulty problem solvers experience as they interact with the problem, importance (degree to which the problem is significant and meaningful to a problem solver), and urgency (how soon the problem should be solved). The choices that problem solvers make regarding these factors determines how difficult everyday problems are to solve. Ill-structured problems are more difficult to solve, in part because they tend to be more complex. The more complex that problems are, the more difficulty students have to choose the best solution method (Jacobs, Dolmans, Wolfhagen, & Scherpbier, 2003). Also, problem solvers represent complex problems in different ways that lead to different kinds of solutions (Voss, Wolfe, Lawrence, & Engle, 1991).

At the base level, problem complexity is a function of external factors, such as the number of issues, functions, or variables involved in the problem; the number of interactions among those issues, functions, or variables; and the predictability of the behavior of those issues, functions, or variables. Although complexity...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Learning to Solve Complex Scientific Problems

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- About the Authors

- PART I COGNITIVE SCIENCE VIEWS OF PROBLEM SOLVING

- PART II SCIENTIFIC VIEWS OF PROBLEM SOLVING

- PART III RESEARCH AGENDA FOR THE FUTURE: WHAT WE NEED TO LEARN ABOUT COMPLEX, SCIENTIFIC PROBLEM SOLVING

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Learning to Solve Complex Scientific Problems by David H. Jonassen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.