Who are children and young people in alternative care?

Children residing in statutory care are collectively referred to as looked after children in Britain and Ireland, and as children in out-of-home care in North America and Australasia. Neither term satisfactorily describes the status of children in long-term statutory care. Increasing numbers of such children exit statutory care to legally permanent placements with caregivers who are not their birth parents under various types of guardianship and adoption orders. These child populations are differentiated by their legal status but not their developmental histories. They have similar need for social and clinical support services. Yet because of their differing legal status, governments have not tended to view them collectively. This book purposely treats them as a single population defined by shared developmental and social histories, namely children and young people in alternative care – a collective term promoted by the United Nations (United Nations General Assembly, 2010). The United Nations employs the term alternative care to encompass all forms of non-parental care provided to children, including that which is legally sanctioned or not (informal care arrangements); that which is meant to be long-term or temporary; and that which is legally permanent or legally impermanent, except adoption. However, in this book the collective term ‘alternative care’ encompasses adoption from statutory care.

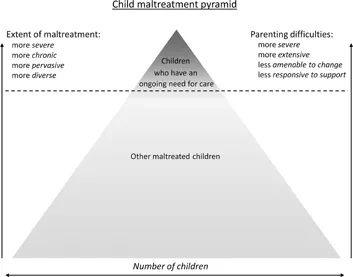

Maltreated children who have an ongoing need for care

Figure 1.1 Child maltreatment pyramid

The protection, psychological development, and well-being of a large majority of maltreated children is best served through varying levels and types of family support services, including specialized parenting interventions and parental drug and alcohol treatment. It goes without saying that providing effective family supports earlier, rather than later, is the key to arresting and preventing further developmental harm for such children. A relatively small proportion of children who are maltreated (abused and/or neglected) by their parents or other guardians have an ongoing need for alternative care. These are children who tend to experience more severe, more chronic, more pervasive, and more diverse maltreatment. The care their parents provide falls well short of ‘good enough’. What differentiates them from other seriously maltreated children is that their parents’ caregiving is not sufficiently amenable to change (e.g. by way of parenting interventions) within developmentally critical timeframes. Figure 1.1provides a diagrammatic representation of these children in relation to other maltreated children.

Within a family preservation framework, the primary purpose of statutory (out-of-home) care is to provide maltreated children temporary protective care, with restoration to their parents being the ultimate goal. Since the 1970s it has been apparent that an increasing proportion of children placed into care either cannot, or should not, be returned home. The observation that many of these children subsequently ‘drift’ in care without acquiring relational permanence, highlighted a concern for the developmental well-being of children growing up in impermanent out-of-home care (Fein & Maluccio, 1992; Rowe & Lambert, 1973). While this has prompted a policy shift in favour of legally permanent placements for children who cannot be safely returned to their parents, large proportions of children placed into legally impermanent out-of-home care remain thus until adulthood (Biehal, Ellison, Baker, & Sinclair, 2010). This reality raises important questions about the developmental well-being of children who grow up in impermanent statutory care, and the extent to which our present models of care support or hinder children’s recovery from early developmental adversity.

At any given time, perhaps a million children in the western world either reside in statutory out-of-home care or have exited such care to adoption or other permanent orders. A substantially larger population encounters these types of alternative care at some time in their childhood.

What proportions of children in alternative care have clinically meaningful mental health difficulties?

Surveys have consistently found that a child in care is more likely than not to have psychological difficulties of sufficient scale or severity to require mental health services, regardless of which country they reside in (Tarren-Sweeney, 2008a). Children in care also endure poorer physical health, higher prevalence of learning and language difficulties, and poorer educational outcomes than other children (Crawford, 2006). More than 30 surveys in North America, Europe, and Australia have reported that children and young people placed in statutory (i.e. out-of-home) alternative care experience much higher levels and rates of mental health difficulties than do children at large (Oswald, Heil, & Goldbeck, 2010; Pecora, White, Jackson, & Wiggins, 2009). These survey estimates are mainly derived from standard caregiver-report rating scales – primarily the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001), and the Rutter Scales (Elander & Rutter, 1996). This is largely accounted for by pre-care exposure to maltreatment, emotional deprivation, and disrupted attachments (Rutter, 2000). Indeed, the scale and complexity of their mental health difficulties is unparalleled among populations defined by family history and legal status rather than psychological development. Although rates vary a little by survey and location, between 35% and 50% of children in care have clinical-level mental health difficulties, and another 15% to 25% have difficulties approaching clinical significance. The scale of their mental health difficul-ties more closely resembles that of clinic-referred children than of children at large.

Rates for different types of alternative care

Although there is considerable variation in care systems, most western jurisdictions shifted emphasis from non-family residential care to foster care through the late 20th century, and more recently to kinship care. The latter trend is partly driven in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada by concern for the identity and well-being of large and disproportionate numbers of indigenous children in care.

Residential care

The small proportion of children placed in residential care have much higher average levels of mental health difficulties and higher rates of mental disorders (Hukkanen, Sourander, Bergroth, & Piha, 1999; Meltzer, Corbin, Gatward, Goodman, & Ford, 2003). This is because residential care is largely reserved for children whose behavioural and social relationship difficulties make family-based care less sustainable – typically following a sequence of placement disruptions. This differentiation is less evident in countries that have retained large residential care systems, such as France (where half of children in care are placed in residential group homes). A recent French survey of adolescents in residential care (N = 183) found that 49% had one or more mental disorders – 2.5 to 3.5 times the rate among French children at large (Bronsard et al., 2011). This is lower than that reported in systems where much smaller proportions of young people are placed in residential care, and is more consistent with estimated rates of disorder for children and youth in foster care.

Kinship care

Conversely, among children residing in family-based statutory care, those placed with kin have lower rates of clinical-level difficulties than those placed with unrelated foster families (Delfabbro, 2016; Holtan, Ronning, Handegård, & Sourander, 2005; Vanschoonlandt, Vanderfaeillie, Van Holen, De Maeyer, & Andries, 2012). The reasons for this are unclear. All other things being equal, children clearly stand to benefit from being raised within their extended biological families. However, these findings are also likely to be partly accounted for by selection effects – whereby children with fewer difficulties are more likely to be sustained in kinship placements. Among the participants of my longitudinal Children in Care Study, many more had transferred from kinship placements to foster placements than in the opposite direction.

Adoption from care

Two recent studies in the United Kingdom measured surprisingly high levels of mental health difficulties among population samples of children adopted from care – comparable to that experienced by children who remain in foster care (DeJong, Hodges, & Malik, 2016; Selwyn, Wijedasa, & Meakings, 2014). These findings confirm the need for post-adoption support services and dispel the notion that children in statutory care who are selected for adoption have fewer psychological and developmental difficulties than those remaining in long-term foster care.

What types and patterns of mental health difficulties are observed among children in alternative care?

More is known about the scale and prevalence of mental health difficulties experienced by children and young people in various forms of alternative care than of the nature, patterns, and complexity of those difficulties. This is largely because most available research data were obtained as outcome measures in studies addressing non-clinical research questions. More than 30 such studies have measured children’s mental health outcomes using standard parent-report survey rating scales, notably the CBCL and the SDQ. These surveys have established that children in alternative care have very high rates of externalizing, internalizing, and attentional difficulties, and proportionately low prosocial behaviour. Diagnostic surveys have also estimated a high prevalence of conduct disorder (17%–45%), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (10%–30%), depression (4%–36%), post traumatic stress disorder (40%–50%), and generalized anxiety disorder (4%–26%) among mixed samples of children and young people in foster and residential care (Blower, Addo, Hodgson, Lamington, & Towlson, 2004 Dubner & Motta, 1999; Famularo & Augustyn, 1996; McCann, Wilson, & Dunn, 1996; McMillen et al., 2005; Stein, Rae-Grant, Ackland, & Avison, 1994). A recent population survey estimated the following rates of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (4th edition; DSM-IV) mental disorders among a sample of 279 6-to 12-year-old Norwegian children: any disorder = 50.9%; emotional disorders = 24.0%; attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder = 19.0%; behavioural disorders = 21.5%; and reactive attachment disorder = 19.4% (Lehmann, Havik, Havik, & Heiervang, 2013).

In recent decades, the mental health of children in alternative care has tended to be framed in terms of the problems measured in population surveys by the CBCL and SDQ, specifically aggression, inattention, and emotional problems – while relationship and trauma-related difficulties have been overlooked. These under-researched problems include attachment-related difficulties, anxiety and dissociative responses to trauma, age-inappropriate sexual behaviour, and self-harm. Yet this was not always so. Early accounts of children in institutional care emphasized their disturbed relationship styles, accompanied by aggressive behaviour, low empathy, and hyperactivity (Wolkind & Rushton, 1994). This was variously described as “affectionless psychopathy” (Bender & Yarnell, 1941), “the affect hungry child” (Levy, 1937), and “institutional syndrome” (Goldfarb, 1949). More recently, research on the problems of Romanian adoptees has revived an interest in the nature of attachment difficulties and inattention/hyperactivity among infants raised in residential care (Kreppner et al., 2001; O’Connor, Bredenkamp, Rutter, & the English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team, 1999).

The Assessment Checklist measures were developed by the author to measure these under-researched mental health difficul-ties. The remainder of this chapter describes the types and patterns of mental health...