![]()

p.1

1

THE IDEA OF EVOLUTION

The oddest thing is that you’re not quite the same person as you were a few seconds ago. You have a memory of picking up this book, and this memory has joined others held somewhere in your biology: how you came to be here today, who you are and even how to read these words.

Something must change amongst the atoms and molecules of your body for you to learn and remember these things. Learning, in other words, is transformative in a very concrete sense – it changes not just our mental world but also our biological form. Learning often accumulates so gradually and quietly that the changes go unnoticed. But some ideas are so profound they entirely alter a person’s view of themselves and what’s around them. And when that idea spreads, it can transform others until the world itself seems changed.

On 15 September 1834, the seeds of one such idea were waiting to be discovered – perhaps the biggest scientific idea of all. The theory of evolution would help us understand how the diverse abilities of species came about, including our transformative ability to learn. On this day, by a small volcanic island 200 miles off the coast of Ecuador, a rowing boat was launched from the HMS Beagle. Its occupants negotiated it along a treacherous and abrasive coastline. Eventually, the crew found a patch of black sand where their craft could avoid being scuppered. A young Charles Darwin stepped out onto San Cristobal Island, one of the Encantada, or enchanted isles (aka “The Galapagos”). These islands had been a foggy sanctuary for pirates raiding Spanish galleons and Darwin was also a treasure seeker – of a type. He was hunting specimens of local animals, but this island did not look promising. In his diary he wrote: “Nothing could be less inviting than the first appearance”. He didn’t know it then, but the treasures he was about to discover would play a critical role in solving the “mystery of mysteries”: how life evolves, and how one species can become another.

p.2

The observations and specimens that Darwin amassed would help him launch the most influential and important theory of our time. And yet, Darwin was not a qualified scientist. Like many young men of his age, he had been pursuing leisure interests while postponing a “proper job”, and he was especially fond of collecting beetles and bugs. He had dropped out of medical school and been pushed into clerical training in Cambridge in readiness for the Church – then the last resort for hopeless young men from good homes. His suitability for the Church was tainted by a dwindling faith and little interest in his studies but the consolation would be a rural parish with the time and opportunity to pursue his collecting. Fate, however, had something else in store. Cambridge led to regular contact and then friendship with a Botany professor called Henslow, with whom Darwin enjoyed many long rambles and collecting expeditions in the surrounding countryside. When Henslow turned down a trip on a survey ship called the Beagle, he suggested Darwin should go. Its captain, Fitzroy, mindful of his predecessor becoming severely depressed and shooting himself, was keen to find company for the two-year voyage ahead. The captain needed someone to eat with, someone who could engage in interesting conversation and keep his demons in check. A naturalist with the skills to collect some interesting specimens would, of course, be a bonus.

In 1836, after five years, Darwin arrived back from his voyage ecstatic to be once more at his father’s home and amongst his sisters. Never again need he feel the seasickness that had followed him around the world. Within days, however, the family welcome had given way to a whirl of social and scientific engagements. His letters from abroad, giving reports of strange animals, breath-taking geology and fascinating peoples, had whetted the appetites of the intellectual and chattering classes. News of his return was spreading. His celebrity status meant dinner invitations, and the opportunity to regale and entice possible funders with his South American tales. While society events rarely excited Darwin, he knew that networking would be vital for establishing himself as a scientist. He would need help from those with scientific credentials, and he would need money, to ensure he could catalogue, research and exhibit his specimens. Between the dinners he toured the institutions where he might be allowed to unpack and place parts of his collection: the Linnaean and British Museum, and the scientific societies. At the Zoological Society, he presented 80 mammals and 450 birds, on the condition that they were mounted properly and described. Amongst these were the famous Darwin finches, although at the time Darwin thought they probably all fed together as the same species, and had no sense they had adapted to different environmental niches. At the Society, the “Superintendent” John Gould quickly perceived he was in possession of a new group of finches containing 12 different species. The media was contacted and Darwin’s birds were set out for display. Within a few weeks, the discovery was paraded by the President of the Geological Society at a meeting where Darwin was elected onto its council. Darwin had been slow to understand he was collecting new species but, in fairness, what counts as a new species remains a subject of debate even today (see box overleaf). Now, however, this realisation stirred an all-important question in him: why is present and past life on any one spot so closely related?

p.3

Within 18 months, Darwin was married, financially independent and living off Gower Street in the centre of London. The massive task of cataloguing, describing and publishing his specimens had really only just begun, and here he was ideally placed close to the institutions and societies that could, if he kept them sweet, support his work. But he was already pondering other, more dangerous issues, ones he had to keep from his new scientific friends for fear of alienating them. Darwin’s analysis of life’s diversity on the Galapagos and its island-specific variation was confronting him with more inescapable questions, such as “Why, on these tiny islands so recently emerged from the sea, were so many beings created slightly different from their South American counterparts?” In 1837, he opened a secret notebook (the “B” notebook) and began to write his thoughts on transmutation – the changing of one species into another. According to his theory, new species were constantly being generated by evolution, rather than appearing randomly or via divine design. Darwin based his arguments on three observable facts: 1) more offspring are produced than can survive; 2) trait differences between individuals influence their ability to survive and reproduce; and 3) these trait differences are heritable. On this basis, the argument follows that trait differences favouring greater fitness are more likely to be passed on, i.e. organisms evolve by a process of natural selection (see box on pp. 6–7).

p.4

Speciation and extinction

The concept of a species is a fuzzy one. When can we say there’s enough difference between two evolving populations to claim we have two species? One widely used definition claims “speciation” has occurred when the two groups can no longer breed with each other.1 Most commonly this happens when a significant number of the population becomes physically isolated due to migration or, as may have happened in the Galapagos, their habitat becomes fragmented. Within this smaller sample, inbreeding can result in a much faster rate of inherited change.

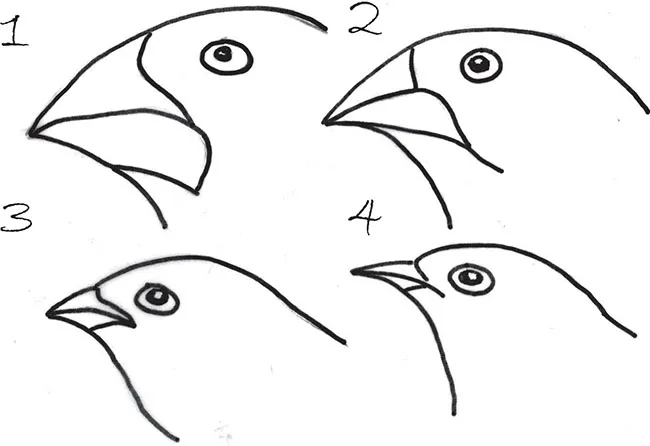

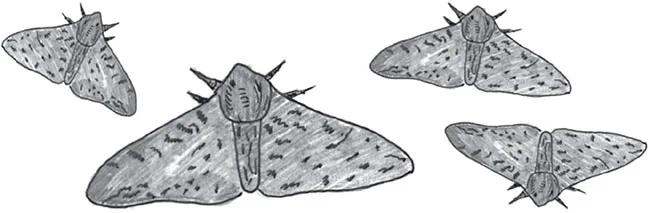

Since Darwin collected his finds on the Galapagos, small island-specific changes in its birds have been seen over just a few decades, as their environment has changed. Those birds who, simply due to random mutation, had beaks slightly more suited to the environment became naturally selected as a result.2 Over a longer time, these changes can accumulate, explaining how different finch species have evolved and come to inhabit different islands, each adapted to the food supply offered by their island. For example, in these finches that were categorised by Gould, the beaks of 1 and 2 (opposite) are ideal for crushing large, hard seeds. While 3 has a beak ideal for grasping larger insects on the ground, 4, unlike these other finches, has the ability to catch and feed on flying insects.

When you think of the natural variation within humans, it doesn’t seem so surprising that Darwin initially thought his finches were the same species. In addition to the normal variation within a species, another challenge of spotting species is that the “can only breed with each other” definition cannot apply to all life forms. It cannot, for example, apply to prokaryotes (single-celled organisms without a nucleus) since these do not reproduce sexually. These represent half the Earth’s biomass and the great majority of its “species”.

p.5

Compared with its beginning, defining the end of a species is much more straightforward. Almost all species known to have shared our planet are now extinct and it seems fair to assume that extinction is the fate of every species. Extinction occurs continuously but spikes have occurred in the background rate. The most dramatic on record was the Permian-Triassic extinction (252 Myr) when 96% of species disappeared. We are presently living (for the time being at least) through the Holocene extinction with rates 100–1000 times greater than background levels, with our own species implicated as the primary cause and global warming set to increase rates further.

But it would be another two decades before this idea was published. Why the delay? After all, you could argue the idea wasn’t that new. In ancient Greece, philosophers had already disputed how easily and fluidly such transmutation might occur. Aristotle had suggested all living forms were variations on a defined set of fixed possibilities or “ideas”. By the eighteenth century, notions of a fixed cosmic order had mostly vanished from scientific thinking about the physical world, but the living world was closer to the divine. Biology in Darwin’s day still clung to notions of fixed natural types, created as part of some supernatural plan. This dominant notion of intelligent design had resisted suggestions by thinkers such as Lamarck that species might transmute. These “free-thinkers” included Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus who, as a man of the Enlightenment, was contemptuous of the idea that God, rather than Nature, created the species. Erasmus was a renowned physician, lover of liberty, supporter of women’s education and staunch opponent of slavery. But his family found many of his views concerning, since his unorthodoxy had gone further. Erasmus enjoyed writing erotic verse and prescribed sex for hypochondria, while his beliefs about evolution proposed “the strongest and most active animal should propagate the species, which should thence become improved”. (That may explain why, in addition to the dozen children with his wives, he also had two with his children’s governess.) In Darwin’s family, evolutionary thinking was already associated with irreligious and immoral thoughts and behaviour – all threats to the status quo of respectable society. While Darwin remained uninterested in religion, his wife was devout in her faith and anxious about his ideas. Her anxiety worried him greatly.

p.6

Natural selection

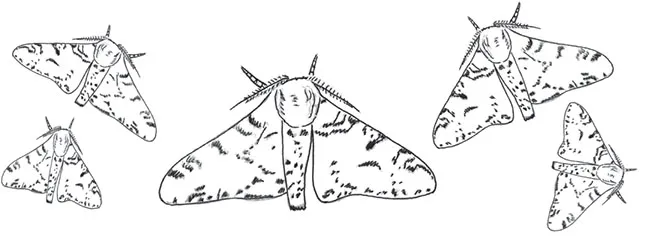

Though evolution tends to be slow and gradual, dramatic changes in the environment can bring about change more rapidly. The most famously observed example of Natural Selection is the pepper moth. Before 1811, only light-coloured pepper moths were known in the UK.

However, by 1848, at the end of the Industrial Revolution, a drastic increase in the dark-coloured variety was recorded around the industrial city of Manchester, where trees were often covered with soot. The Clean Air Act in the 1950s was followed by a decline in the number of dark relative to lighter-coloured pepper moths.3

Evolutionary theory prompted the idea that a light colour was more effective camouflage for these moths in a clean environment and a dark colour was a better way to survive predators when the environment became polluted.4,5 Those moths whose colour was better fitted to their background survived and reproduced in greater numbers, and so that colour became predominant in the population. Understanding pepper moths from an evolutionary perspective helps us appreciate, understand and explore how they are “fitted” to their environment. It prompted further experiments that have confirmed the importance of colour for an individual moth’s survival6 and further questions about the genetics of moth colour.

Darwin knew that the damage potential for grand ideas about the origin of species extended well beyond his family. He was aware that evolutionary ideas can be exploited by both left- and right-wing politicians, much as they continue to be today. Since returning home, the gathering tumult in England was providing a lesson in the dangers. The Rev. Thomas Malthus had suggested that any population size, if unchecked, would grow exponentially and outpace the food supply. Darwin had made a similar observation in the natural world, i.e. that more offspring are produced than can normally survive. Malthus, however, made his own interpretation of this for policy – and had begun reflecting on what options should be implemented for checking population growth. He proposed not only that moral restraints should be encouraged (e.g. sexual abstinence), but also that those suffering poverty and other circumstances he regarded as “defects” should not be allowed to reproduce. He promoted these policies as the available options to disease, starvation and war. On this basis, the poor did not need charity since this might expand their numbers; instead, they just needed control and discipline. Buoyed by Malthusian principles, the “New Poor Law” meant no more outdoor charity. Either the poor competed with everyone else or they would find themselves in the new workhouses that were springing up everywhere. Those outraged by inequities such as this “punishment of the poor” came together in a nation-wide protest movement (the Chartists) to support a people’s charter. Riots ensued, soldiers were called out and some demonstrators were shot. One incident hemmed the Darwin family into their London home as troops charged crowds a few yards from their door.

p.7

A few days after those troop charges, in 1842, Darwin, along with his wife and children, retreated to a new and somewhat desolate home in the Kentish North Downs – far away from the chaos, unrest and noise of a restless London. This would be where Darwin could study and develop his theory in the solitude he now loved. Gone were the sounds of the Chartist riots in the streets below, but the thought of “coming out” with his ideas was still not attractive. He was no longer the naïve young man who had boarded the Beagle to pursue his hobby and avoid a job in the Church. If not picked up by Malthusians, his ideas might be adored by revolutionaries seek...