- 211 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Anatomy of Humor

About this book

Humor permeates every aspect of society and has done so for thousands of years. People experience it daily through television, newspapers, literature, and contact with others. Rarely do social researchers analyze humor or try to determine what makes it such a dominating force in our lives. The types of jokes a person enjoys contribute significantly to the definition of that person as well as to the character of a given society. Arthur Asa Berger explores these and other related topics in An Anatomy of Humor. He shows how humor can range from the simple pun to complex plots in Elizabethan plays.Berger examines a number of topics ethnicity, race, gender, politics each with its own comic dimension. Laughter is beneficial to both our physical and mental health, according to Berger. He discerns a multiplicity of ironies that are intrinsic to the analysis of humor. He discovers as much complexity and ambiguity in a cartoon, such as Mickey Mouse, as he finds in an important piece of literature, such as Huckleberry Finn. An Anatomy of Humor is an intriguing and enjoyable read for people interested in humor and the impact of popular and mass culture on society. It will also be of interest to professionals in communication and psychologists concerned with the creative process.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Anatomy of Humor by Arthur Asa Berger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Movements in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

THEORETICAL CONCERNS

1

A Glossary of the Techniques of Humor: Morphology of the Joke-Tale

What sits in a tree and jumps on girls?

Jack the Grape.

What sits in a tree and jumps on boys?

Jack the Grapefruit.

Jack the Grape.

What sits in a tree and jumps on boys?

Jack the Grapefruit.

What follows is a catalogue, in alphabetical order, of the basic techniques of humor. What I will do is list as many of these techniques as I have been able to discover (in an examination and analysis of a number of different works of humor), provide examples of the technique, and explain how the technique functions. This will give us a means of taking any example of humor (created at any time, in any genre, in any medium) and showing what it is that generates the humor and provokes (often) laughter—or whatever state it is that we feel when we encounter something humorous.

Since works of humor are often incredibly complex, we will frequently find a number of different mechanisms operating at the same time, though one mechanism is often dominant. At times some of my explanations of a given technique will be fairly extended, but I have tried to be as succinct as I can possibly be in most cases.

I have used jokes (for the most part) in this glossary for two reasons. First, they are short and easy to reproduce, and second, they enable me to deal with the techniques of humor in an immediate and direct manner. But let me emphasize that I do NOT believe that telling jokes is a good way for the average person to be funny. A joke, as I understand it and as it has been traditionally defined, is a story with a punch line—that is used for comic effect. When you tell a joke you are, in essence, generally performing someone else’s material. Some people can do this very well, but many can’t. (That is why I was tempted to give this glossary a subtitle—“How To Be Funny Without Telling Jokes for Those Who Tell Jokes Without Being Funny.”) I believe it is through the use of the various techniques listed and explained in this glossary that people can create their own humor. So why use other people’s?

In certain respects this glossary is similar to Vladimir Propp’s pathbreaking book, Morphology of The Folktale. In this book Propp listed a number of what he called “functions” (actions of characters as they relate to the plot) and these “functions” are, he argued, at the heart of all narratives. They are the building blocks on which stories are constructed. I had not read Propp when I prepared my glossary, but I realized, like him, that the subject matter of a story or joke was frequently irrelevant. It was often the case that a given joke I found had different subjects. A joke in one joke book was about a minister and the same joke, in a different book, was about a professor.

If subject or theme wasn’t all important, then, I concluded, technique was and so I elicited as many techniques of humor as I could find, not asking why something was funny (we may never really know) but what was it that generated the humor. I might point out that we must always consider reversals of techniques, though I do not deal with this in the glossary. Thus, if exaggeration is one important technique, so is the negative or reverse form of this, understatement. Both involve exaggeration, but in different directions, so to speak.

In the “Jack the Grapefruit” joke there are a number of humorous techniques at work. It has an element of facetiousness about it, with a character with a bizarre name, Jack the Grape. We find the word “rape” buried in this name, so there are allusions involving sexuality. In the second part of this joke there is an allusion to Jack’s homosexuality, in which Grape is tied to “fruit,” a slang term for homosexual males. A grapefruit is not a Grapefruit. With the capital “G” a grapefruit becomes a homosexual. The form of this “joke” is a riddle—but I am not concerned, in my Glossary, with forms since I believe techniques are more basic than forms. A riddle can be turned into a standard joke (“Did you hear about this character who sits on trees and jumps on girls? His name is Jack the Grape.”) What is more important is the nonsense, the wordplay, and other techniques.

The analysis of humor (and of jokes in particular) should involve the following steps:

- breaking down the example of humor used into its main elements or components—that is, isolating the various techniques used to generate the humor;

- Rating the techniques—deciding which technique is basic and which techniques are secondary.

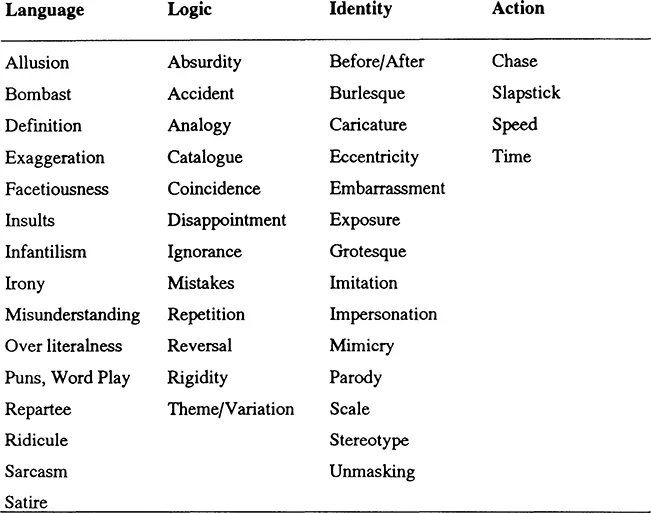

This is based on the assumption that humor has a process aspect to it which can be separated into various parts and analyzed. Any example of humor “shields” various techniques that generate the humor, and something is funny or humorous, in the final analysis, not because of the subject matter or theme but because of the techniques employed by whomever created the humor. There are four basic categories under which all my techniques of humor can be subsumed:

- Language. The humor is verbal.

- Logic. The humor is ideational.

- Identity. The humor is existential.

- Action. The humor is physical or nonverbal.

These categories are useful in that they give us a sense of what kind of humor is being produced, but the techniques are the essential matter to consider in analyzing humor. (Almost all of the techniques described in this glossary are functional, but some, such as Burlesque, are really classificatory and are included so as to provide the reader with a sense of how certain techniques of humor relate to one another. In the Burlesque section, for example, it is the techniques listed under this catch-all technique, that are functional.)

While I’m not perfectly satisfied with the list of techniques that is to follow (and the jokes and other humor used to exemplify each technique), the glossary does offer us an opportunity to understand the mechanisms at work in humor—and, by implication, to use these techniques to generate our own humor, should we desire to do so. That is why I have given this chapter the subtitle “Morphology of the Joke-Tale.” It is an allusion to Propp but it is also a good description of what I have done.

Categories and Techniques of Humor

These techniques were elicited by making a content analysis of all kinds of humor in various media and are, as classification schemes should be, comprehensive and mutually exclusive. I’ve not been able to find other techniques of humor to add to my list. The focus on techniques means that I treat certain topics, such as parody, as a technique rather than a form or a genre. I have done so because I think that recognizing techniques is more important than using traditional categories.

Absurdity, Confusion, and Nonsense (logic)

Didn’t I meet you in Buffalo?

No, I never was in Buffalo.

Neither was I. Must have been two other fellows.

Why do elephants paint their toenails red?

So they can hide in cherry trees.

Have you even seen an elephant in a cherry tree?

No.

It must work, then.

What is it that hangs on the wall in bathrooms and one can dry one’s hands on?

A towel.

No! A herring.

But for goodness sakes, a herring doesn’t hang on a wall.

You can hang one there if you want to.

But who would dry his hands on a herring?

You don’t have to ...

Absurdity and its related forms—confusion and nonsense—seems to be relatively simple, but it is not . . . and its effects may be quite complicated, as Freud pointed out in his discussion of nonsense humor. Absurdity works by making light of the “demands” of logic and rationality as we traditionally know them. This absurdity doesn’t necessarily take the form of silliness (though in many children’s jokes it does) but may be an example of a relatively sophisticated philosophical position.

If life is absurd, as many existentialists suggest, then the humor of absurdity can be seen as a means towards realism: an understanding of humanity’s predicament and our possibilities in an irrational universe. This explains why the plays of Beckett and Ionesco (and others) fascinate us and speak to us in such a profound manner.

In the Buffalo joke, our sense of order and intelligibility are played with. There are two tricks played upon us. First, the man who claimed to have met a person in Buffalo reveals that he had never been there. But if that was all there was to the joke it would be relatively flat. The last phrase, “it must have been two other fellows,” pushes the joke into the absurd.

The second joke plays with logic and reasoning processes. It is asserted that elephants paint their toenails red so they can hide in cherry trees. When it is confirmed that elephants have never been seen hiding in cherry trees, this is taken as proof of the assertion. Our attention is redirected from the ridiculous nature of the proposition to its seeming truthfulness.

The third joke deals with our sense of possibility and probability. It is unlikely that one would dry one’s hands in a bathroom (or anywhere) with a herring hanging on the wall, but is possible or conceivable that one might wish to do so. The last line, “you don’t have to,” turns the humor back on the reasonable person; he becomes foolish by virtue of his good sense on normality.

We all seem to need to impose our sense of logic and order on the world, and when we come across situations or instances where our logic doesn’t work, we react by being puzzled and, in certain cases, amused.

Accident (logic)

“Ladies and Gentlemen, The President of the United States ... Hoobert Heever.”

Newspaper Headlines:

Thugs Eat/ Then Rob Proprieter

Officer Convicted Of Accepting Bride

Advertisement:

Sheer stockings—designed for dressy wear, but so serviceable that many women wear nothing else.

In my classification system I have distinguished among three seemingly similar yet different ways or producing humor: Accidents, Mistakes (or Errors), and Coincidences. The first of these methods is demonstrated by the material reproduced above. It stems from things like slips of the tongue (fluffs), letters left off or improperly placed in headlines (typos), inadvertent and ambiguous constructions of sentences, etc.

An accident is different from a mistake or an error. A mistake stems from ignorance or imprudence while an accident is essentially a matter of chance. A coincidence involves a chance correspondence of some kind, that generally leads to some embarrassment, but need not involve error. We find accidents humorous as long as they are not serious and do not generate strong anxiety.

Allusions (language)

A Lieutenant was given two weeks leave to go on his honeymoon. At the end of his leave he wired his commanding officer: “It’s wonderful here. Request another week’s extension of leave.” He received the following reply. “It’s wonderful anywhere. Return immediately. “

A troupe of actors come into a county to perform a number of plays by Shakespeare. The Sheriff of the county tells them that they cannot advertise the plays they will be presenting. The director of the troupe puts a sign up at the theatre and everyone knows what plays will be shown.

- Wet

- Dry

- Miscarriage

- 3”

- 6”

- 9”

What were the plays?

- Midsummer’s Night’s Dream

- Twelfth Night

- Love’s Labor Lost

- Much Ado About Nothing

- As You Like It

- The Taming of the Shrew

Allusions are the bread and butter of everyday humor and are very much tied to social and political matters as well as situations which have a sexual dimension (and sometimes, of course, to both). It is, in fact, the allusiveness of much of our humor that makes it such a useful and important means of getting at a given society’s interests and preoccupations. In some cases, such as well publicized scandals, etc. just the mention of a person’s name is enough to evoke laughter. There is an element, here, of an unsuccessful attempt, on the part of the person involved in the scandal, to escape from embarrassment.

The joke about the Lieutenant is based on the conventional joy of sexual relations. The humor in the joke revolves around a misunderstood allusion. We must assume that the honeymooning officer meant by “it” the pleasure of life in general when he said “it.” But this “it” was interpreted (with good reason, one might add) by the commander to mean “sexual intercourse.” Since one of the comic joys of civilized life seems to involve interfering with people’s sexual lives and denying them their pleasures, there seems to be an element of spite in the joke.

Allusions are tied to mistakes, errors, gaffes, stupid things people say and do that become known, for one reason or another. They are tied to information that people have. The allusion is a cue which enables us to recall, once again, these mistakes, etc. The event that is alluded to must not be terribly serious or important. If it were, the allusion would not generate humor but, instead, something like pain or anxiety. Thus, our allusions often deal with sexual matters, personality traits, behavioral characteristics, and other matters which may be embarrassing but not painful. We are recalling material that was seen as humorous once and enjoying it once again or we are interpreting things in ways that will generate humor by embarrassing others.

The joke about the Shakespearean plays is a kind of riddle that involves tying the names of plays to various sexual phenomena: wet dreams, being unable to perform sexually, the size of penises, etc. The humor is based on allusions of a sexually disguised nature and stems from seeing connections between a signifier and a play that can be connected to that signifier. Part of the humor also stems from the ability to connect all of the plays to sexuality.

Allusions are consensual forms of humor, then. The allusion tells us what we can legitimately poke fun at and also tells ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1 Theoretical Concerns

- 1 A Glossary of the Techniques of Humor: Morphology of the Joke-Tale

- 2 Anatomy of a Joke

- Part 2 Applications

- 3 The Telephone Pole with the Braided Armpits: Ethnic and Racial Jokes and American Society

- 4 “On Me You Can’t Count”: An Interpretation of a Jewish Joke with Relevance to the Jewish Question

- 5 Jewish Fools

- 6 Mickey Mouse and Krazy Kat: Of Mice and Men

- 7 Comics and Popular Culture

- 8 Mark Russell in Buffalo

- 9 A Cool Million

- 10 Twelfth Night

- 11 Huckleberry Finn as a Novel of the Absurd

- 12 Healing with Humor

- 13 Comedy and Creation

- Bibliography

- Names Index

- Subject Index

- Jokes and Humorous Texts Index