The biggest obstacle to interpreting the history of food may be that we think we already know about it. As Chapter 1 showed, the legacies of past assumptions, ideologies, nostalgias, and reform movements have contributed to powerful narratives and images that have the ring of established truths. And these have created remarkably durable images, especially of what a farm is and how the history of food production and consumption has unfolded in different places.

The second big obstacle is that once we start thinking about it more seriously, we often realize that we actually know very little and that piecing together a better-informed sense of how we’ve ended up with our current industrialized food system is an immensely complicated task. This chapter works to chart a path between these two positions—the big unconscious assumptions and the challenge of seeing familiar foodscapes in different ways. We propose building an interpretation that keeps issues of scale front and center and that starts from a particular set of questions about environment, economy, and energy.

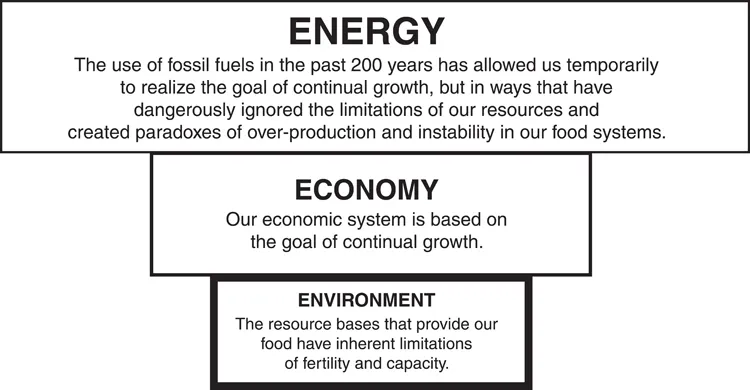

To help organize an interpretive approach, we suggest a “top line” narrative that can help to frame interpretation around those questions. This approach is keyed to the timeline in the Appendix and emphasizes the fundamental disjuncture between an economic system based on ideas about limitless growth and a set of physical resources—particularly agricultural lands and the other resource bases that provide our food—that are, by their very nature, limited. Many contemporary advocates of a less purely profit-driven model of economic life speak of a “triple bottom line” that takes into consideration social equity and environmental health as well as economic growth. We are advocating here that museum interpreters, educators, and exhibit designers should think about a similar “triple top line” when developing an interpretation of food and farming histories.

While this chapter aims to set out a useable framework for rethinking food and farm history, it also recognizes that even more than most histories, this one is very much in the process of being pieced together, in dialogue with many kinds of people listed in the previous chapter—food producers, advocates, consumers, researchers, environmentalists, policy makers—who are working to rethink our collective relationship with land, food, energy, and each other. Public historians and museum interpreters have much to offer in this process: ways of considering the available evidence about the past, an ability to frame good critical questions, and skill at moving often-fragmentary historical materials into an accessible narrative shape. But the point here is less about creating finished, authoritative knowledge than about finding ways to share our processes of inquiry with others who are grappling in real time with the same big questions. The gaps in our own knowledge and the challenges of overcoming them may actually be an asset in this case. They provide opportunities for public historians and museum interpreters not only to model skills, but also to see our work as part of a collective effort at addressing urgent social and environmental questions.

The Mainstream Narrative

Here is the outline of the big story about food that we think we know. It begins with the very long time span of human life on the planet and narrows to the U.S., particularly the northeast, the region of the U.S. where small-scale farming first “declined” and therefore where a great deal of effort has been expended to understand, defend, and revitalize it.

Humans have been around for more than 200,000 years, and for the vast majority of that time they have subsisted by hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants. The question of when, why, where, and how people began intentionally cultivating and domesticating wild species is a fundamental one for archeologists and anthropologists, and it is far from settled. But current research suggests that agriculture developed in a number of places around the world starting about 12,000 years ago and that it spread from at least ten independent centers of development, the earliest being in the Middle East, eastern China, Mesoamerica, and Polynesia.1 Although cause-and-effect relationships are difficult to pinpoint, it seems clear that farming is historically linked with expanding populations, increasingly sedentary settlement patterns, and specialized, often hierarchical social and political arrangements. More complex food systems, in other words, have long been linked with changes in the scale on which humans live.

By the Middle Ages, 700 or 800 years ago, the dominant form of subsistence in Europe consisted of mixed-crop cultivation and animal husbandry within a generally feudal system of land ownership, a model that diffused around the world as Europeans began to build colonial empires after the sixteenth century. Just as important, ideas about this kind of agricultural society—the link between individual land ownership and political power, the notion of the natural world as a resource to be exploited by human ingenuity, an emphasis on intensive productivity and a particular kind of work-discipline, and a kinship system that gendered farmers and landholders as male and passed along land through the male line—spread with European colonialism. In sometimes-contradictory ways, those ideas contributed to the building of settler societies like those in North America. Settlers’ aspirations toward land ownership sometimes helped fuel anti-colonial and democratic movements, while the monopoly on landholding by males of European descent helped suppress other models of agriculture and subsistence, particularly those of indigenous and enslaved people who had long practiced a flexible and effective mix of hunting, gathering, farming, and food preservation tailored to their particular environments and climates. In the pre-Contact era, agriculture was embraced unevenly by different indigenous groups, but even where it was widespread and sophisticated, it was widely misunderstood by colonizers because its cyclical, seasonal, lineage-based patterns of settlement and occupation were so radically different from that of the Europeans.

By the start of the nineteenth century, the main components of today’s dominant agricultural system were becoming established in much of North America and certainly in the northeastern U.S.: northern-European-style farming within an economic system increasingly driven by market-oriented considerations and pushed by the new tools, desires, and expectations of industrialism. Colonial American farmers were never as fully self-sufficient as our nostalgic images of them have sometimes led us to believe.2 But until the early nineteenth century, farmers’ decision-making about crops and prices was shaped far more by immediate and local factors (like weather and personal relationships) than by what more distant markets would bear. By the time more commercial markets began to come to the fore in the early nineteenth century, however, agriculture was already a maturing rather than an expanding sector in the northeast. Small-scale, locally or regionally oriented farming seemed slow and unproductive by comparison with the heightened efficiency and economic opportunity of industrial production, prompting many younger people to go into industry, seek larger farms along the advancing western frontier, or at the very least embrace the logic and methods of the new industrial economy (Figure 3.1).3

The familiar narrative about older farming areas in the American northeast is that they fell into decline once farmers moved west to larger, more fertile farms. The case of New England gives us a useful way to see this dominant narrative in action. The taken-for-granted history of New England is that its soils are generally poor and rocky, which led ambitious farmers to move, often after tapping out the limited fertility of their original farms and leaving behind an iconic landscape of old stone walls running through the newer-growth forest that has reclaimed formerly cleared hillsides. This familiar story isn’t entirely untrue—New England did lose farmland and farmers over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—but it’s not entirely true, either. The region’s soils are mixed, but acre for acre, its farms are actually among the most productive in the country—just on a smaller scale.4 In fact, New England’s overall farm production actually increased right through the nineteenth century, not peaking until 1910.5 But a closer reading of the historical record shows that farmers in the region have continued to farm productively and worked to maintain the fertility of their land as best they could. Starting about 200 years ago, though, they were doing it within an economy that increasingly demanded more productivity and seemed to provide the tools to achieve it.

Westward expansion and increasing industrialization and productivity make up, to a very large extent, the familiar mainstream story that is told about the American food system. That story is interwoven with the history of farm policy, which will be explored in Chapter 4, and it helped create the nostalgia for older, smaller-scale kinds of farming that we have already seen as a contributing factor to the ways in which agriculture tends to be presented at historic sites. Farms got larger and more specialized; management of food production became more scientific and interlinked with large-scale markets; yields were increased through new technologies and human-made “inputs”; canals, railroads, and finally trucks and airplanes helped expand food markets and networks of distribution as the age of muscle power gave way to steam and then to the petroleum that dominates not only transportation but many aspects of how we live—and eat—today. In the Cold War decades of the mid-twentieth century, this cluster of methods went global, giving rise to what has been termed the “Green Revolution.” For humanitarian, economic, and geopolitical reasons, many non-industrialized countries adopted the technologies of high-input industrialized farming, exponentially increasing yields and helping establish a framework for the globalized food markets that exist today.

The overall movement toward higher productivity and longer-distance food systems is also intercut with countless examples of people resisting the logic of large-scale, market-driven agriculture. But over time, the “alternatives” have repeatedly failed to carry the day. In the U.S., as elsewhere, indigenous groups have fought largely unsuccessful battles to hold onto their foraging, hunting, and farming territories. Nineteenth and early twentieth century agricultural “improvers” and reformers advocated for small farmers to adopt new scientific methods and approaches, without recognizing how these were already changing the rules of the game so that farming on a small scale was less and less viable. Activism and political movements sparked by farmer resistance, perhaps most notably in the “Populist” fervor of the late nineteenth century, have tended to founder on the big question of whether capitalism needs to be rejected or merely reformed. In the South, both white champions of small-scale agriculture and black farmers struggling to stay on the land were ultimately undone by markets and policies—including price supports for commodity agriculture and soil-conservation measures that reclaimed “submarginal” land from farming—favoring more industrialized production. Small-scale foodways have often been relegated to the status of curiosities, encountered by mainstream diners only at cultural festivals or urban ethnic restaurants. Seemingly radical ideas from the early twentieth century, like the “organic” approach proposed by Sir Albert Howard, actually drew on deep peasant farming traditions from Europe, Asia, and elsewhere, but these remained on the fringes until the more comprehensive environmentalism and neo-agrarianism of the 1960s and 1970s. Even now that it has been more widely embraced, the logic of industrialism and capitalist markets has made itself felt: the mainstreaming of organic food has been dubbed “big organic” by critics who see it as merely a somewhat kinder, gentler version of industrialized commodity farming.6

By the turn of the twenty-first century, the dominant system seemed to have become “too big to fail.” It is supported on every side by policy, infrastructure, the advertising industry, learned habits of convenience and mobility, and a long history of efforts to provide safe, abundant, and affordable food for all. The story that we know is essentially a winners’ version: technological improvements and efficiencies trumped less-effective methods, creating winners and losers along the path to a modern, reliable food system (Figure 3.2).

A Counter-Narrative

Today’s food movement may represent the most extensive moment yet of questioning the “too big to fail” and “get big or get out” logic of that system. The contemporary movement draws on earlier critiques and alternatives but also on an ever-greater body of evidence about the environmental, social, and economic costs of industrialism, especially how the greenhouse gases it pumps into the earth’s atmosphere are destabilizing the global climate. Our massive, heavily capitalized and subsidized, technologically sophisticated food system—hugely dependent on fossil fuels and responsible for enormous amounts of greenhouse gas emission—may have become too big to survive rather than too big to fail, threatening our survival rather than ensuring it.7 This brings us back to the shift in viewpoint that is the starting point for this book. We are proposing that public historical interpretation of food and farming should be based in a counter-history of agriculture that can speak directly to the impulses and questions of audiences who are recognizing those problems and seeing food as one important way to start addressing them.

This counter-history retells the familiar story of agricultural expansion and technological progress from a different angle. This is not just the historian’s usual response of “Well, it’s actually more complicated than that.” Rather, it places the whole narrative on a different foundation and questions the consequences of many aspects of modernity, industrialism, capitalism, and fossil fuel use. Questioning them does not mean discounting them entirely or denying that they have produced many advantages for humans, but it lets us see these big contexts more clearly and avoid the trap of assuming they are inevitable and unchangeable. It takes a longer view of short-term gains and asks about their longer-term consequences. And it calls attention to the expansive impulses at the heart of the modern world and the way those impulses have been linked with ever more sophisticated technologies and ever more ambitious projects (like “ending hunger” and “feeding the world”).

The counter-narrative helps uncouple farming from ideas about both progress and civilization, on the one hand, and purity and naturalness, on the other, that have historically been attached to it, and have proven to be powerful—and deeply contradictory—in Western imaginations. It calls into question not just the dominant model of food production but the whole human-centric way of understanding the non-human world it is built on. It upends the hierarchy that puts people at the top of the food chain, with mammals a little lower, cold-blooded animals and plants lower yet, and micro-organisms barely present in the model except as problems to be eradicated. And it exposes the very uneven ways in which the benefits of industrial agriculture have been and continue to be distributed, even within well-meaning attempts to address those inequities.

The counter-narrative also presents food production as a much more collaborative venture among humans and other species, in which visible and charismatic creatures like draft horses and baby lambs are much less central than pollinators or the microbial beings that enable soil fertility as well as processes like digestion and fermentation. From this perspective, the scientific agriculture of the past two centuries is not so much a triumph of human inventiveness as a sudden loss of knowledge about how to assi...