![]()

PART I

AFRICA CASE STUDIES

![]()

| 1 |

| VALUING TIME SPENT COLLECTING WATER IN A KENYAN TOWN1 |

| Hugo van Zyl, Thomas Store and Anthony Leiman2 |

| ______________________ |

WATER COLLECTION

The state of water provision services in a community can have a significant effect on the quality of life of the inhabitants. Many people in developing countries (and particularly women) spend a significant portion of their day hauling water from sources to their homes. Enhanced access to environment-improving services such as water provision can yield substantial benefits in the form of productive time saved.

Different options for improved water delivery services such as yard taps, handpumps, and standposts result in varying amounts of time saved because they cut out the need to haul water from more distant sources. The choice of system does however involve a trade-off between increased costs and the benefits of time saved. Attaching a value to the time that people spend collecting water thus indicates the economic benefits of improved access to water services, which can then be compared with the estimated costs of such services, to assist decision-making on appropriate service provision.

DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY

Objectives and Focus

This chapter reviews a study by Whittington et al (1990a), which attempted to value the time that people spend collecting water, using as an example a small town in Kenya.

The Inter-American Development Bank had assumed that time savings should be valued at 50 per cent of the market wage rate for unskilled labour in the local economy. Although they had no empirical basis for this, estimates of the value of time from studies of people's travel mode choices in developing countries had indicated that people typically value travel time savings at less than their market wage rate (Bruzelius, 1979; Yucel, 1975). The relevance of these findings to time savings from improved water access was unknown though, hence the need to determine the value of time spent collecting water, and in so doing test the Inter-American Development Bank's assumption.

Responding to this deficiency, the study presented two methods of estimating the value of the time spent hauling water based on revealed willingness to pay. The study illustrated the application of these two methods in Ukunda — a small town of 5000 inhabitants, situated 40 kilometres south of Mombasa, in Kenya. The following water sources are available to the residents of Ukunda:

•A pipeline which runs through the town, and which has only 15 private connections;

•Licensed water kiosks which sell water directly to the people; or water vendors who buy water from the kiosks and then deliver it from house to house.

•Six open wells and five handpumps that can be used free of charge by anyone.

Methodology

Both of the methods used in the study were based on discrete choice theory and the aim of both was to estimate values based on the prefer-ences revealed by individuals through their choice of water service. The data were used in a discrete choice theory framework to determine upper and lower bound estimates of the value of time spent collecting water.3 Given discrete choices, utility (satisfaction) functions for individuals were formulated, based on their revealed preferences (in this case revealed by their actions in purchasing water and their answers to a questionnaire). The utility derived from using the three different water sources was expressed as a function of the attributes of each source.

In the first part of the study the following attributes (which varied between sources) were assumed to determine utility: the price of the water, its collection time per litre and its taste. A simplifying assumption is made for the purposes of the calculations, and taste is left out as a determinant of utility, leaving only price and collection time. The household's utility per unit of water can then be obtained.

In the first part of the study the analysis uses discrete choice theory. This works directly with the utility functions instead of through demand functions, which would have been the case if continuous choice theory had been used. The conceptual framework suggested by discrete choice theory is as follows:

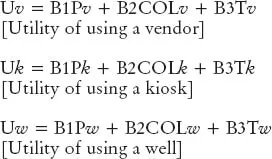

Among J exclusive alternatives (in this case, water sources), household h will choose alternative j over alternative i if and only if:

Since each of the three water source alternatives differs in the three source attributes (P = price; COL = collection time per litre; T = taste), the additive utility of each of the three water sources is given by:

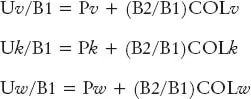

The Bs are parameter values of the indirect utility functions representing the household's preferences. For the purposes of the calculations, the influence of taste is ignored and the assumption is made that the household's choice of source is based solely on collection time and cash price. Dividing the indirect utility functions by B1 gives the household's utility per unit of water:

The Coefficient (B2/B1) is the value of time spent carrying water. Assuming that the alternative with the highest utility (in this case meaning the alternative with the lowest total price per litre including collection costs) will be chosen, with the upper and lower bounds for the value of time spent being calculated as follows:

Household chooses a kiosk:

This implies that Uk > Uv and Uk > Uw which yields an upper bound of (Pv - Pk)/COLk and a lower bound of Pk/(COLw - COLk).

Household chooses a vendor:

This approach reveals two lower bounds of (Pv — Pk)/COLk and Pk/COLw. If the household's value of time were less than the higher of these two lower bounds, it would rationally switch to either the kiosk or open well.

Household chooses an open well:

This approach yields two upper bounds of Pv/COLw and Pk/(COLw - COLk). If the household's value of time exceeds the lower of these two upper bounds, it would have an incentive to switch to either a kiosk or avendor.

The second part of the study is based on a random utility theory approach, which incorporates household characteristics as well as the source characteristics that were used in the first part of the study. Some inconsistencies in observed behaviour are inevitable, and these are assumed captured by a random term which is added to the systematic term in the household's random utility function so that:

where V is the systematic term and E is the random term yielding the following utility function for household h choosing water source i:

where

| TIME | = Collection time per day including travel time, queue time, and fill time (expected to have a negative influence on choosing a source); |

| CASH | = Total amount of money paid for collecting water per day, ie, the cash price times the amount of water consumed per day (expected to have a negative influence on choosing a source); |

| TASTE = | Household's perception of the taste of water from open wells — equalled to one if the taste is poor, zero otherwise (expected to have a negative influence o... |