![]()

Part I

Music and Style in the Classical Period

![]()

1

Defining the Classical Period

There is perhaps no other period in music history that has fired the imagination more than the Classical Period. It was a time when much of our modern thought was formulated and developed, when scientific achievement finally began to break loose from the fetters of religion that had dictated its concordance with doctrine, when political rearrangements spelled the demise of the feudal order and fostered the creation of nations defined by their language and culture, and when the focus in social life, philosophy, and the arts began to revolve around the human element. There was, for the first time, belief in a progressive future for humankind, expressed in the epithet ad astra per aspera (to the stars through difficulties or challenges), indicating that human beings were to achieve a future by themselves, no matter what the cost. This, in turn, meant that the rigid class structures that had been in existence for over a millennium began to break down, aided and abetted by a renewed interest in a global perspective as another wave of exploration began to bring Europe into contact with other cultures around the world, stimulating new thoughts and concepts.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Europe still adhered to the style known as Baroque. The style of Louis XIV, with its complete authoritarian rule by the monarch and rigidly stratified social structure, was epitomized by the resplendent court at Versailles, and culture itself was based on extravagance and opulence. The political divisions were like the arts, ornate, shifting, and subject to intricate divisions of chiaroscuro (light and shadow). Empires were either monolithic, like France and England, or kaleidoscopic like the Holy Roman Empire and Italy, with alliances and noble families shifting constantly. For example, when Spanish king Carlos II, a member of the Habsburg family, died in 1700, it was his intent to pass the crown on to Philippe of Anjou, the grandson of Louis and a Bourbon. This led to the War of the Spanish Succession that lasted for a decade and a half, brought to a conclusion only because the Habsburg emperor himself passed away in 1711. A realignment of political power was deemed important to maintain balance among the realms and thus to avoid the general destruction similar to that which had marred the seventeenth century’s Thirty Years’ War. By 1740, further political changes, such as the changeover in the United Kingdom from the House of Orange to the Hanoverians in 1717, had occurred, thus weakening the power of the courts and allowing for social and political changes to happen. During the Classical Period, these changes manifested themselves in ways unimaginable in earlier times, from the American War of Independence beginning in 1776 to the chaotic French Revolution of 1789 to the rise of a popular dictator (and, later, emperor) Napoleon Bonaparte, almost a decade later. Such a political ferment has led to this being called the Age of Revolution.

The Classical Period was not, however, solely determined by political events. Rather, the concept of revolution spread across all aspects of cultural life, even as the power and prestige of the courts and church waned. The same era has been called the Age of Enlightenment due to the shift in focus away from doctrine and dogma toward a more liberal (in the literal sense of the term) attitude that encouraged new philosophical precepts, a wider range of intellectual thought, and freedom of expression. One only needs to look at the views of French philosopher Voltaire, who said, “Dare to think for yourself,” or Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who noted that “[m]an was born free, and he is everywhere in chains; those who think themselves the masters of others are indeed greater slaves than they” to understand the seismic shift in perception during this time. This, in turn, led to more humanistic philosophies by such men as Immanuel Kant, who proclaimed, “Sapere aude! ‘Have courage to use your own reason!’—that is the motto of enlightenment” in his Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Criticism of Pure Reason) of 1781, as well as the blunt statement of Johann Gottfried Herder: “The people need a master only as long as they have no understanding of their own.”1

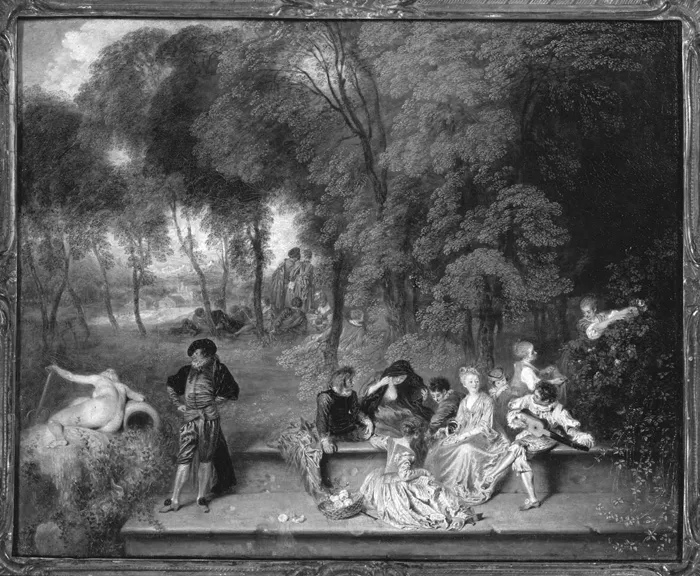

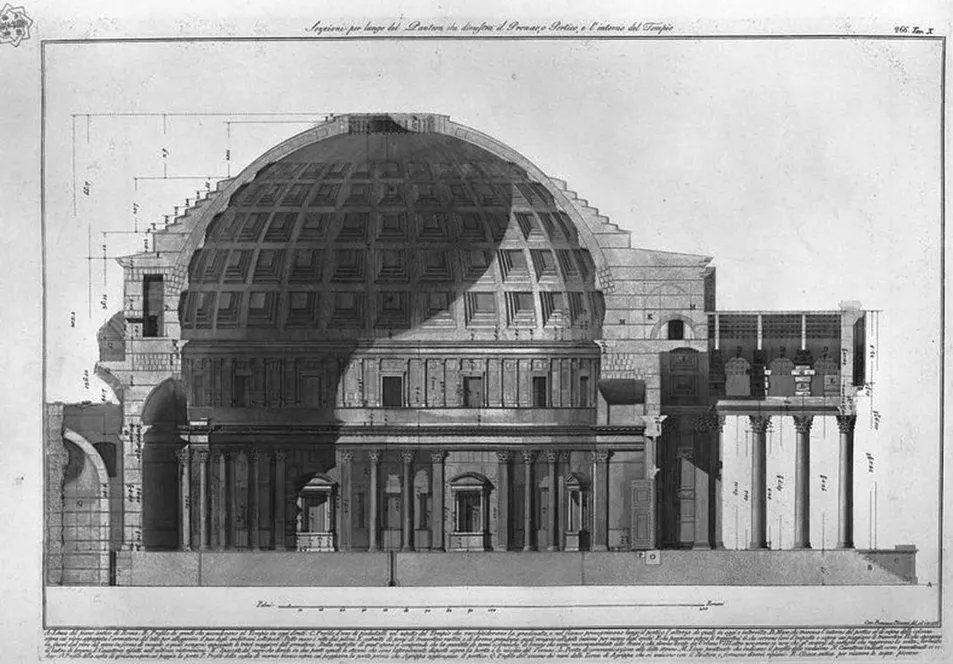

One can find the same sort of intellectual creativity in the arts during this time. The often voluptuous and extravagant art forms of the Baroque shifted to more humanist subjects. In painting, the pictures of Jean-Antoine Watteau were harbingers of this new, more realistic age by depicting convivial domestic scenes, such as his painting The Pleasures of Love from 1716 (Figure 1.1). Portraits of people and places replace the penchant for allegorical and religious-inspired works. French artist Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun depicted her subjects with an eye toward fashion and elegance, while her British colleagues, Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds, both sought to portray their portraits with a human intimacy. Elsewhere, Italian artists such as Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) broadened their scope to depict conventional scenes of places; he, in particular, painted the city of Venice enumerable times from different perspectives so that one almost seems to view the places as if one were actually there (Figure 1.2). In architecture, a renewed study of the works of ancient Rome and Greece provided a foundation for the creation of structures that were without the gaudiness and opulence of palaces like Versailles, opting instead for Classical symmetry and beauty. For example, this sketch of the famed Pantheon in Rome by Giovanni Battista Piranesi is precise and without fantasy (Figure 1.3). Not all artists of the Classical Period were stuck on realistic portrayals, however. Swiss artist Henry Fuseli explored the darker side of humanity, producing nightmarish pictures that blended humans and supernatural beings, such as The Nightmare, in which a demon squats on top of a supine woman, a vision that is both horrific and erotic at the same time (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.1 Jean-Antoine Watteau, The Pleasures of Love (1719)

In the literature of the Classical Period, developments in style paralleled those in music. The range and depth of the works in all fields, from drama (which often contained incidental music) to novels, was

Figure 1.2 Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal), Piazza San Marco Venezia (ca. 1723–1724)

significant. One could find raw and satirical works, such as Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels of 1720 (or his rather more pointed pamphlet “A Modest Proposal” of 1729 in which he advocates cannibalism of the Irish), or more refined comedies, such as La putta onorata (The Honorable Maiden) by Italian playwright Carlo Goldoni, many of which derive from the time-honored commedia dell’arte. Both Voltaire and Rousseau wrote plays, and both tragedy and comedy were continuously written, published, and performed in eighteenth-century France. One of the more controversial playwrights was Pierre Auguste Caron de Beaumarchais, whose trilogy Le Barbier de Séville, Le Mariage de Figaro, and La Mère coupable (The Barber of Seville, The Marriage of Figaro, The Guilty Mother, respectively) was censored as insulting to the nobility. Yet, the first two works were transformed into popular operas, the first by Giovanni Paisiello and the second by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The closest parallel to the development of musical style, however, could be seen in German-speaking lands. The so-called Enlightenment style of Johann Christoph Gottsched, a professor at Leipzig University and a literary power, featured static plots and was often an adaptation of French Baroque models. He also produced theoretical works on German poetry (1730) and drama (1740–1745), which he intended would be seen as the models for a national literature. Unfortunately, he was seen as overly pedantic, and by 1748, with the emergence of his student Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a more emotional and dramatic style of literature known as Empfindsamkeit, his style of literature quickly vanished.2 Lessing’s most important works began with the play Miss Sara Sampson in 1755, which was regarded as a bourgeois tragedy by his contemporaries. His colleague in Hamburg, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, took the style further by promoting the plays of William Shakespeare in translation and producing his own epic Messias (1748–1773) in imitation of John Milton’s epic Paradise Lost. Here, the musical connection was more direct; Klopstock was a friend of composer Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach in Hamburg and often collaborated with him.

Figure 1.3 Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Interior Sketch of the Pantheon in Rome (1790)

Perhaps the most radical change in literature came in 1774 with the publication of the novel Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (The Sorrows of the Young Werther) by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in which a young psychotic man is completely ruled by his own passions and forms a fatal attachment to a married woman (Figure 1.5). This heralded the introduction of a new style of literature, known as Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress), in which extreme passions predominate. This style, whose name was taken from a turgid tragedy by Maximilian Klinger by the same name,3 featured unrestrained human emotions, extremes of temperament, dark imagery, and hopeless disaster. As with Empfindsamkeit, the models were the works of Shakespeare and an alleged “Celtic bard” named Ossian, the content of which featured dark and brooding nature and violent primitive emotions of the characters.4 Although the literary Sturm und Drang was short-lived—the final work by Friedrich von Schiller was the 1784 Die Räuber (The Robbers)—it nonetheless set the stage for the Gothic horrors and supernatural literature of the Romantic Period of the nineteenth century. The most representative work by Goethe, however, was his play Faust that was begun about the same time as Werther but not published in its final version until 1808. The story, which fascinated Romantics throughout the nineteenth century, involves a professor who sells his soul to the devil (Mephistopheles) in order to regain his youth for a time. It is a clear representative of the more modern and expansive drama that both Goethe and Schiller embraced in the middle of the 1780s, known as Weimar Classicism. Here, authors sought to merge the various eighteenth-century literary styles into a more humanistic form, incorporating the human emotions (and occasional passion) of the Empfindsamkeit and Sturm und Drang with the higher poetic speech of the Enlightenment. Goethe himself noted that it owed much to what can be termed “neoclassicism,” that is, the reinvention of the dramaturgy of classical Rome and Greece but with the addition of modern aesthetics, structure, and content. Other authors who adhered to this movement included Christoph Martin Wieland, who as will be shown was one of the major figures in the development of Classical Period German dramatic opera.

Figure 1.4 Henry Fuseli (Johann Heinrich Fussli) The Nightmare (oil on canvas, 1781)

Finally, a word needs to be said about the Classical Period as the age of discovery. With the focus on human creativity and humanism came a renewed interest in scientific achievement. From 1730 to 1800 Europe was in the throes of a wave of scientific advances, once the restrictions on it were lifted. A few should be mentioned here. First, there were a number of attempts at flight, the first since the radical ideas of Leonardo da Vinci several centuries earlier. While the airplane (and glider) lay in the future, the concept of lighter-than-air belonged to the Montgolfiére brothers Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne. While at work as paper manufacturers, they noticed that heat made the paper rise and, by 1783, had flown a balloon in Paris for almost ten kilometers (Figure 1.6). Second, in 1781 Scottish inventor James Watt created the first reliable steam engine, producing power to operate machinery and functioning as the precursor to the Industrial Revolution of the following century. Third, Edward Jenner discovered in 1797 that an inoculation could prevent one of the scourges of Europe, smallpox, beginning the path toward disease vaccines. Finally, astronomer and scientist Frederick William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus in 1781, the first outside the six known in antiquity, by bu...