- 445 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published as Scientific Research, this pair of volumes constitutes a fundamental treatise on the strategy of science. Mario Bunge, one of the major figures of the century in the development of a scientific epistemology, describes and analyzes scientific philosophy, as well as discloses its philosophical presuppositions. This work may be used as a map to identify the various stages in the road to scientific knowledge.Philosophy of Science is divided into two volumes, each with two parts. Part 1 offers a preview of the scheme of science and the logical and semantical took that will be used throughout the work. The account of scientific research begins with part 2, where Bunge discusses formulating the problem to be solved, hypothesis, scientific law, and theory.The second volume opens with part 3, which deals with the application of theories to explanation, prediction, and action. This section is graced by an outstanding discussion of the philosophy of technology. Part 4 begins with measurement and experiment. It then examines risks in jumping to conclusions from data to hypotheses as well as the converse procedure.Bunge begins this mammoth work with a section entitled ""How to Use This Book."" He writes that it is intended for both independent reading and reference as well as for use in courses on scientific method and the philosophy of science. It suits a variety of purposes from introductory to advanced levels. Philosophy of Science is a versatile, informative, and useful text that will benefit professors, researchers, and students in a variety of disciplines, ranging from the behavioral and biological sciences to the physical sciences.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Philosophy of Science by Mario Bunge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy & Ethics in Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy & Ethics in SciencePart IV Testing Scientific Ideas

12. Observation

13. Measurement

14. Experiment

15. Concluding

So far we have dealt with scientific ideas and some of their applications. Henceforth we shall tackle the problem of finding out the extent to which those ideas fit facts. Since this fitness is estimated through experience, we shall study the empirical procedures whereby ideas concerning facts are checked.

Empirical operations are made in science with cognitive aims or with practical ones. Cognitively directed empirical operations are those performed in order to produce data, generate modest conjectures, or test hypotheses and theories. Practically directed empirical operations are those aiming at testing rules of procedure or concrete systems— materials, instruments, persons, organizations. In brief, empirical operations can be classed into cognitively directed or knowledge-increasing (data-gathering, hypotheses-generating, or hypotheses-testing), and practically directed or power-increasing (rules-testing or systems-testing). In the following, emphasis will be laid on cognitively directed empirical procedures.

Now the results of empirical operations aiming at advancing our knowledge are insignificant by themselves: they have to be interpreted and evaluated—i.e. some “conclusions ” must be drawn from them. In other words, if such empirical results are to become relevant to scientific ideas then certain inferences must be performed. This is why the present and last part of the book closes with a chapter devoted to the evaluation of hypotheses and theories in the light of scientific experience. In this way we close the loop that starts with facts prompting the questioning that elicit ideas requiring empirical tests.

12

Observation

The basic empirical procedure is observation. Both measurement and experiment involve observation, whereas the latter is often done without quantitative precision (i.e. without measuring) and without deliberately changing the values of certain variables (i.e. without experimenting). The object of observation is, of course, an actual fact; the outcome of an act of observation is a datum—–a singular or an existential proposition expressing some traits of the result of observing. A natural order to follow is, then: fact, observation, and datum. Our discussion will close with an examination of the function of observation in science.

12.1 Fact

Factual science is, by definition, concerned with ascertaining and understanding facts. But what is a fact or, better, what does the word ‘fact’ mean? We shall adopt the linguistic convention of calling fact whatever is the case, i.e., anything that is known or assumed—with some ground—to belong to reality. Accordingly this book and the act of reading it are facts; on the other hand the, ideas expressed in it are not facts when regarded in themselves rather than as brain processor.

Among facts we usually distinguish the following kinds: state, event, process, phenomenon, and system. A state of a thing at a given instant is the list of the properties of the thing at that time. An event, happening, or occurrence, is any change of state over a time interval. (A point event, unextended in time, is a useful construct without a real counterpart.) A flash of light, and the flashing of an idea, are events. From an epistemological point of view, events may be regarded either as the elements in terms of which we account for processes, or as the complexes which we analyze as the confluence of processes. In science, events play both roles: taken as units on a given level, they become the objects of analysis on a deeper level.

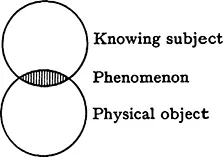

Figure 12.1 Phenomena as facts occurring in the transactions of the knower with his environment.

*Are there unanalyzable events, i.e. ultimate facts in terms of which all others must be accounted for and which could not conceivably become the object of further analysis? According to one school of thought events such as the quantum jump taking place when an atom emits a light quantum are not further analyzable. We cannot here discuss this question in detail, but as cautious philosophers we should surmise that, from our failure to analyze an event either empirically or theoretically, we are not warranted to conclude that the event itself is atomic or irreducible. The fault may lie with our tools of analysis, either empirical or conceptual—as has so often been the case along the history of science. There might be elementary, i.e. unanalyzable events, but this we may never know: we should always try to analyze them and it should always be too soon to admit our defeat.*

A process is a sequence, ordered in time, of events and such that every member of the sequence takes part in the determination of the succeeding member. Thus, usually the sequence of phone calls we receive during the week is not a process proper, but the sequence of events beginning with a phone call to our doctor and ending with the payment of his bill includes a process. If analyzed deeply enough, most events are seen to be processes. Thus, a light flash consists in the emission, by a large collection of atoms at slightly different times and at random, of wave groups that are propagated with a finite velocity. It is no easy task to trace processes in the tangle of events. A process is rarely given in experience: in science, at least, processes are mostly hypothesized. Thus, stars are not seen to evolve, but star evolution models must be imagined and then tested by recording and interpreting events such as the traces left by starlight on photographic plates.

A phenomenon is an event or a process such as it appears to some human subject: it is a perceptible fact, a sensible occurrence or chain of occurrences. Rage is not a phenomenon except for the subject suffering a fit of rage; but some of the bodily events accompanying a fit of rage—some acts of behavior—are phenomena. Facts can be in the external world but phenomena are always, so to speak, in the intersection of the external world with a cognitive subject (Fig. 12.1.) There can be no phenomena or appearances without a sensible subject placing itself in an adequate observation position. One and the same event (objective fact) may appear differently to different observers, and this even if they are equipped with the same observation devices (see Sec. 6.5). This is one reason why the fundamental laws of science do not refer to phenomena but to nets of objective facts. The usage of ‘phenomenon’, though, is not consistent: in the scientific literature ‘phenomenon’ is often taken as a synonym of ‘fact’—just as in ordinary language ‘fact’ is often mistaken for ‘truth’.

(An old philosophical question is, of course, whether we have access to anything non phenomenal, i.e. that does not present itself to our sensibility. If only the strictly empirical approach is allowed, then obviously phenomena alone are pronounced knowable: this is the thesis of phenomenalism. If, on the other hand, thinking is allowed to play a role in knowledge in addition to feeling, seeing, smelling, touching, and so on, then a more ambitious epistemology can be tried, one assuming reality—including experiential reality—to be knowable if only in part and gradually: this is the thesis of the various kinds of realism. According to phenomenalism, the aim of science is to collect, describe, and economically systematize phenomena without inventing diaphenomenal or transobservational objects. Realism, by contrast, holds that experience is not an ultimate but should be accounted for in terms of a much wider but indirectly knowable world: the set of all existents. For realism, experience is a kind of fact: every single experience is an event happening in the knowing subject, which is in turn regarded as a concrete system—but one having expectations and a bag of knowledge that both distort and enrich his experiences. Accordingly, realism will stimulate the invention of theories going beyond the systematization of experiential items and requiring consequently ingenious test procedures. We have seen at various points, especially in Secs. 5.9, 8.4, and 8.5, that science both presupposes a realistic epistemology and gradually fulfils its program.)

Finally we shall call entities, or physical things, concrete systems— to distinguish them from conceptual systems such as theories. A light wave is a concrete thing and so is a human community, but a theory of either is a conceptual system. The word ‘system’ is more neutral than ‘thing’, which in most cases denotes a system endowed with mass and perhaps tactually perceptible; we find it natural to speak of a force field as a system, but we would be reluctant to call it a thing. By calling all existents “concrete systems” we tacitly commit ourselves— in tune with a growing suspicion in all scientific quarters—that there are no simple, structureless entities. This is a programmatic hypothesis found fertile in the past, because it has stimulated the search for complexities hidden under simple appearances. Let us be clear, then, that by adopting the convention that the protagonists of events be called concrete systems, we make an ontological hypothesis that transcends the scope of the special sciences.

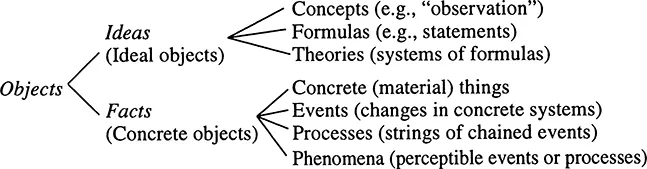

Events and processes are what happens to, in, or among concrete systems. (We disregard the metaphysical doctrine that things are just sets of events, for having no foot on science.) Events, processes, phenomena, and concrete systems are, then, facts; or rather, we shall count them in the extension of the concept of fact. Facts are, in turn, a kind of object. Object is, indeed, whatever is or may become a subject of thought or action. Things and their properties are objects; again, concepts and their combinations (e.g., propositions) are objects, but of a different kind: they are often called ideal objects. Facts, the concern of factual science, are objects of a different kind: they may be termed concrete objects. In brief,

What about physical properties, such as weight, and relations, such as subordination? Shall they be counted as material objects or as ideal objects? If we do the former we shall be forced to conclude that properties and relations can exist by themselves, apart from concrete things and their changes (events and processes); also, that there could exist concrete things destitute of every property. Either view is at variance with science, which is concerned with finding out the properties of concrete things and the relations among them—and, on a higher level of abstraction, with investigating the relations among properties and relations as well. If, on the other hand, we count properties and relations as ideal objects, then we are led to hypothesize that concrete objects have ideal components—the “forms” of ancient hylemorphism. And, being ideal, such properties and relations would not bear empirical examination, which would render factual science unempirical.

What are then physical properties and relations if they can be classed neither as material nor as ideal objects? The simplest solution is to declare them nonexistent. But then we would have again things without properties and events without mutual relationships—and consequently we would be at a loss to account for our success in finding laws. There seems to be no way out but this: there are no properties and relations apart from things and their changes. What do exist are certain things with properties and relations. Property-less entities would be unknowable, hence the hypothesis of their existence is untestable; and disembodied properties and relations are unknown: moreover, every factual theory refers to concrete things and th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Part III—Applying Scientific Ideas

- Part 4 IV—Testing Scientific Ideas

- Afterword

- Author Index

- Subject Index