![]()

Part 1

The Reading Process

Part I consists of a single chapter, namely, chapter 1, “Introduction to the Reading Process: A Definition of Reading.” This chapter describes reading as developing a representation or mental model of text by relating what is on the page to one’s own fund of knowledge or experience. The closer the representation of the reader is to the mental representation of the writer when he put his ideas into print, the better the reader will comprehend what the writer intended, and the better the communication between writer and reader will be. Chapter 1 further describes reading as a synthesis of word recognition and comprehension. Reading involves the recognition of printed stimuli, but the development of meaning or comprehension is the essence of reading. Reading is about meaning. Chapter 1 also introduces the discussion of reading as a sensory process, as a high-level thinking process, and as a language, a psycholinguistic, and a communication process. It examines both the phonological and direct visual access routes to meaning, and the role of the semantic and syntactic contexts in the construction of meaning. It discusses the surface and deep structure of reading and affirms that the interactive model explains reading better than do either the top-down or bottom-up models singly.

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to the Reading Process:

A Definition of Reading

I. | Introduction |

II. | Reading as Interpretation of Experience |

III. | Reading as Interpretation of Graphic Symbols |

IV. | The Word Identification Process |

V. | The Comprehension or Decoding Process A. Smith’s View of Comprehension B. Levels of Comprehension |

VI. | The Surface and Deep Structure of Language |

VII. | Additional Characteristics of Reading A. Reading as a High-Level Thinking Process B. Reading as a Language and Psycholinguistic Process |

VIII. | The Semantic and Syntactic Context in Reading A. Semantic Processing B. Syntactic Processing |

IX. | Models of Reading: Bottom-up, Top-Down, Interactive A. Bottom-up Models B. Top-Down Models C. The Interactive Model |

X. | The Phonological and the Direct Visual Access Routes to Meaning A. Subvocalization B. Prelexical Phonological Recoding C. Direct Visual Access D. Postlexical Phonological Recoding |

XI. | Summary |

Chapter 1

Introduction to the Reading Process:

A Definition of Reading

Chapter 1 examines important issues in reading: What is reading? What is the role of word recognition and comprehension? What are the surface and deep structure in reading? To what extent is reading a thinking process? What are the implications of defining reading as a language, a psycholinguistic, and a communication process? Is reading only a psycholinguistic guessing game or is it something more? What are the roles of the semantic and syntactic contexts? What model, the bottom-up, the top-down, or the interactive, best explains what happens in reading? And, is access to meaning achieved through a process of direct visual access (i.e., going directly from the printed word to meaning), a process of phonological recoding (i.e., going from the printed word to sounding of the word and then to meaning), or both? We first examine definitions of reading.

Definitions of reading are generally divided into two major types: (a) those that equate reading with interpretation of experience generally, and (b) those that restrict the definition to the interpretation of graphic symbols. The first is a broader category and encompasses the second; most reading definitions are related to one or both. Let us consider more closely some of the definitions which make up these categories.

Reading as Interpretation of Experience

With the first type of reading definition, in which reading is equated with the interpretation of experience generally, we might speak of reading pictures, reading faces, or reading the weather. We read a squeaking door, a clap of thunder, a barking dog, or another’s facial expressions. The golfer reads the putting greens, the detective reads clues, the geologist reads rocks, the astronomer reads stars, the doctor reads the symptoms of illness, and the reading teacher reads the symptoms of reading disability.

The definition of reading that came out of the Claremont College Reading Conference fits this first category. In the Conference’s Eleventh Yearbook, Spencer (1946) wrote, “In the broadest sense, reading is the process of interpreting sense stimuli…. Reading is performed whenever one experiences sensory stimulation” (p. 19). Benjamin Franklin in 1733 in Poor Richard’s Almanac had such a definition in mind when he wrote: “Read much, but not too many books” An important implication of the definition of reading as interpretation of experience is that pupils must be readers of experience before they can become readers of graphic symbols. They must first be readers of the world. Pupils cannot read symbols without having had those experiences that give the symbol meaning. This last implication will interest us more at a later point in this text.

Reading as Interpretation of Graphic Symbols

Turn now to the second type of definition of reading, that which equates reading with the interpretation of graphic symbols. Most definitions of reading given in professional textbooks are of this second type. Writers have furnished us with multiple descriptions of reading, often with varying nuances and emphases. They have described reading as involving the comprehension and interpretation of the symbols on the page (Harris – Sipay, 1975, 1985); as a complex interaction of cognitive and linguistic processes with which readers construct a meaningful representation of the writer’s message (Barnitz, 1986); or as giving significance intended by the writer to the graphic symbols by relating them to what the reader already knows (Anderson, Hiebert, Scott, & Wilkerson, 1985; Dechant, 1964, 1970, 1982; Duffy & Roehler, 1986).

Reading is also described as the reconstruction of the message encoded graphically by the writer; as constructing meaning from print (Gillett & Temple, 1986); as making sense of written language (Gillett & Temple, 1986); and as a process of information search or information processing. It is described as an interactive process involving both the reader’s previous fund of knowledge and the words in the text; it is a process of putting the reader in contact and in communication with the ideas of the writer which are cued by the written or printed symbols; it is a process of building a representation or a mental model of text (Perfetti, 1985). In this text reading means building a representation of text by relating what is on the page to one’s own fund of experience. When the reader’s representation of text essentially approximates that of the writer, genuine reading occurs.

The Word Identification Process

Reading is additionally described as a synthesis or integration of word identification and comprehension, in which the absence of either makes true reading impossible.

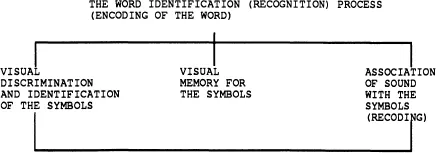

In reading, the obvious need is that the words on the page be identified and recognized by the reader. Reading begins as a sensory process and as a word identification process. Word identification or encoding of the printed word involves three basic processes (see Figure 1–1): visual discrimination and identification of the symbols; visual memory for the symbols; and, generally recoding, pronunciation of the symbols, or association of sound with the symbols.

Figure 1–1. The word identification (recognition) process (encoding of the word)

The purpose of all communication is the sharing of meanings; the purpose of all reading is comprehension of meanings. But it is the symbols or words that must carry the burden of meaning between the communicators. The written symbols are the writer’s tools for awakening meaning in the reader. Communication through writing and its reciprocal, reading, requires such a sign system. Without the graphic input there can be no reading. Good readers often are such because they are capable of rapid and accurate word recognition. They have automatized the word identification skills. They have committed thousands of words to their sight or recognition vocabulary and can recognize them instantly with minimum language cues.

It is obviously important that readers make a visual discrimination of the symbol, whether it be car, ςνωθι ςαυτον, or phlogiston, and that they visually discriminate one symbol from the next. Readers must identify the graphic symbols or develop a percept of the graphic stimulus. They need to be able to process the visual array of letters and words. Beginning readers in particular need to learn to perceive the significant contrastive features, those elements of the visual configuration that distinguish one letter from another letter or one word from another.

Matching of letters and words is not enough. The task readers face is not one of looking for words that match. They must be able to see the difference in words. They need to discover the critical differences between two letters or two words, between a given word and any other word. They need to learn what the distinctive features of written language are.

Unfortunately, visual discrimination of the symbols alone is generally not enough for beginning readers to go to meaning. Such readers commonly need to be able to see that cat represents /kǎt/, and that ςνωθι ςαυτον represents /gnōthē soutǔn/. They benefit when they can move from the graphic code (which they see) to the sound code (which they have already learned), when they can associate sound with the printed symbol, and when they can recode from the graphic to the spoken code. Reading, thus, for some readers is not simply visual discrimination of the symbols. It often includes the ability to recode. Both aspects are generally significant elements of the reading process, especially in the learning-to-read process. Indeed, a major goal of word-identification teaching is to help children develop a code that permits them to move quickly and easily from the written to the spoken code; in other words, to see why cat represents /kǎt/, and why cent represents /sěnt/.

A common model for reading is based on reconstructing a spoken message from a printed text and making the same meaning responses to the printed text that one would to the spoken message. Bannatyne (1973) noted that visual symbols (the graphemes) represents sounds (the phonemes), not concepts or meanings. The printed word is a code for the auditory/vocal language. According to Bannatyne, only the sounds strung together in auditory/vocal words and sentences represent meaning.

Thus, for many teachers, the most natural way for teaching young children to read has been to go through the spoken word. The teacher says to the child: “Look at this word. This word is /kǎt/.” The spoken word is the familiar stimulus, while the written word is the novel stimulus. Gradually, with repeated associations between the written and the spoken word, the child brings to the written word the same meaning he previously attached to the spoken word.

Undoubtedly, beginning, and even mature, reading often includes recoding. Reading comprehension is clearly related to the ability to pronounce (recode) the printed words. Poor readers tend to have poor recoding skills. They make more than twice the number of oral reading errors per 100 words that good readers do. The beginning reader recodes more frequently than the fluent reader. The question of whether or not all readers characteristically recode to gain access to meaning will concern us later in the chapter. Our answer will be different for beginning and for fluent readers.

The Comprehension or Decoding Process

We have already noted that the central purpose or sine qua non of all reading is the comprehension of meaning. Reading is thus more than word identification. If reading were simply a word-identification or word-naming process, children would be good readers when they could identify the word immediately at sight or when they could recode or name the printed symbols or words. Reading is more than the ability to identify or to pronounce the words on the printed page, or to go from the graphic to the spoken code. It is more than giving the visual configuration a name. This is recoding, but is not decoding. Decoding requires the reader to reconstruct the message encoded graphically by the writer. Decoding occurs only when meaning is associated with the written symbols and only when the meaning that the writer wanted to share with the reader has been received.

It is not enough to put one’s own stamp of meaning on the words. The reader must follow the thought of the writer (Goodman et al., 1987; Langman, 1960). Comprehension occurs only when the reader’s construction or representation of text agrees substantially with the writer’s representation or his intended message. Only then does true communication via reading take place.

Hittelman and Hittelman (1983) note that “reading is the process of reconstructing from printed patterns the ideas and information intended by the author” (p. 4). In a later text (1988), Hittelman says: “Reading entails both reconstructing an author’s message and constructing one’s own meaning using the print on the page. A reader’s reconstruction of the ideas and information intended by an author is somewhat like a listener’s reconstruction of ideas from a speaker’s combinations of sounds” (p. 2). In the same text Hittelman notes that “Reading comprehension is partly the reconstruction of an author’s intended meaning” (p. 416).

Reading is not simply a matter of communicating signs or symbols, letters or words. It is concerned with the communication of meaning. Thus Gephart (1970) remarks, that reading refers to an interaction by which meaning encoded in visual stimuli by an author becomes meaning in the mind of the reader.

Obviously, reading of graphic symbols consists of two processes: the visual process involved...