eBook - ePub

Native Races and Their Rulers

Sketches and Studies of Official Life and Administrative Problems in Niger

- 596 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Native Races and Their Rulers

Sketches and Studies of Official Life and Administrative Problems in Niger

About this book

An adequate account of Charles Temple's personal background and, the details of his career have been given by Dame Margery Perham in Lugard: the years of authority1; by D. J . M. Muffett in Concerning brave captains2 and by Kirk-Greene in his recently published The principles of native administration in Nigeria—selected documents 1900-1947.3 Since these works are likely to be familiar to readers of this Introduction, there seems no point in repeating them here. In this book, the author explores more with his ideas. First Published in 1968. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Native Races and Their Rulers by Charles Lindsay Temple in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & African History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTION.

THE part of the British Empire where the data on which the conclusions arrived at in the following pages were, for the most part, obtained is that known to-day as the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. The Northern areas were known when they were first taken over by the Government from the Royal Niger Company in the year 1900, and up to the end of the year 1913, as Northern Nigeria. Now, since the amalgamation of Northern with Southern Nigeria the whole area is named Nigeria. The administration is entrusted to a Governor-General with two Lieutenant-Governors, one for the Northern and one for the Southern provinces (which form the Protectorate), while for the Colony there is one Administrator.* The Head of the Government is assisted by an Executive Council and his more important acts are performed as Governor-General-in-Council. The Protectorate is divided up for administrative purposes into Provinces with a Resident in charge of each, assisted by a staff of District Commissioners. Besides these, an important part, as will be seen in the following pages, in the work of administration is played by what are termed the Native Administrations. This is more particularly the case in the Northern Provinces where each great Muslim Filane Emirate, such as Sokoto, Kano, Katsena, Zaria,Bauchi, etc., and the Emirate of Bornu (which is not Filane), forms a petty Government of its own in many respects. In the Southern Provinces there are several important Pagan units such as the Yoruba Chieftainatcs of Abeokuta, Ibadan, and Oyo, which, to a certain extent, manage their own affairs, as do the Northern Emirates.

There are the usual technical Departments, some are very large, the Railways Department for instance has a thousand miles of open lines. For the most part these are responsible to the Governor-General direct through the Central Secretariat, while some of the smaller Departments are responsible to him through the Lieutenant-Governors. There is no officer corresponding to the Colonial Secretary, or the Secretary to Government, in other Colonies, but each Lieutenant-Governor and the Administrator has his own Secretariat, making four in all, including the Central Secretariat. There is a Chief Justice with a staff of Puisne judges; an Attorney-General advises the Governor-General and each Lieutenant-Governor has a Legal Adviser. I will not go closely into the details of the administrative machinery which does not differ materially from that in other Colonies and Protectorates.

There is nowhere to be found in the Empire, I think, a territory which includes, in so comparatively small an area and population, so great a diversity of climatic conditions, and ethnographical, sociological and sectarian divisions. And yet the total area of 350,000 square miles and the population just short of twenty millions allows of each of these different areas and sections of humanity to exist on such a scale as to exhibit in a normal and natural manner the features characteristic to such conditions. Within the limits of Nigeria are to be found sections of the human race and areas of the earth’s surface typical of very nearly every class of society and of every description of climate to be found in the Empire within the tropics.

Taking the sociological and ethnological point of view first we have in the Emirate of Sokoto a good example of the effects of Islam at their best. The tenets of this creed appear to have appealed especially to the naturally haughty, reserved, and serious character of the Filane, a Semitic race allied to the Arabs and Jews, and at Sokoto and its neighbourhood we find in large numbers Muslims who carry out in the strictest manner the spirit as well as the letter of the Koran and the Commentaries. They belong to the Maliki sect for the most part. No acts of religious fanaticism have as yet occurred among the people, on the contrary they have been particularly law-abiding and have shown real loyalty to the Government on more than one occasion, but it is easy to foresee that injudicious treatment might lead to such acts among people whose religion is a really governing influence in their daily lives. As might be expected the habits of these people are strictly frugal and simple—all pomp, show, and ostentation, the wearing of fine clothes of bright colours, even the building of large houses, is considered “bad form” among them. A plain white robe, and a not too clean one at that, is considered the correct dress in these parts. A man may take a pride in the strength and beauty of his horse and the temper of his sword, all other earthly considerations are vanity. So it comes about that though they are in cast of mind oriental of the orientals, the appearance of a Sokoto crowd or town or gathering of chiefs is liable to lack the colour which we have come to look for in oriental and tropical studies. Nevertheless they fit in with their surroundings, which, for their part, have nothing tropical about them. The great sandy waterless stretches which, however, bear good crops in the rains, are for the most part, devoid of incident; the vegetation is sparse and meagre, and trees scarce and not of luxuriant growth. Further, for several months of the year a strong North East desert wind sweeps over the country. This wind, known as the Harmattan, is charged with fine particles of sand which have the effect of throwing a neutral silvery veil of mist over the landscape, producing an effect not without beauty, but quite destroying all colour.

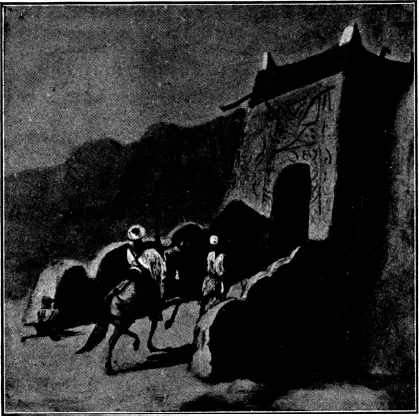

Leaving Sokoto and proceeding South, say to Kano, the characteristics of the people alter, there is more intermixture of negro blood, they are less austere, their bodies are less attenuated, they look much happier, what they lose in refinement they gain in vivacity and the picturesque. They wear bright clothes, admirably matching the colours; the more wealthy build large cool houses of sun-baked clay, but often of elaborate design. The arches which the native architects succeed in turning, without the help of drawings to act as a guide in the execution of the preconceived plan, are veritable feats of simple engineering and are often of great artistic value. Nevertheless, it is evident, from their expressions, that amongst these natives, as is always the case where Islam has spread to any appreciable extent, are many who take life extremely seriously. Throughout the Filane states to the South of Sokoto (and in Bornu where the climate is similar to that of Sokoto, but the Semitic blood is wanting), the general characteristics of, the people are similar to those in Kano. Only as you travel South there is more rude savage display and less courtly dignity, and the people get less reserved and more open in their speech. This is sometimes taken as indicating a bolder, franker habit of mind. But such is not the case: what is really indicated is a more rudimentary mode of life, thought, and greater absence of self-control.

In all the refinements of life such as polite manners, court etiquette, hospitality, and, in general, good behaviour and constraint, even to the point of suppressing all outward show of inner feelings, the Filane Emirs of the North and all their chiefs and notables and even the more well-to-do merchants had progressed before our arrival about as far as it is possible so to do. It would be hard to surpass the manners of these people, indeed the very peasants not infrequently put one on one’s mettle in matters of behaviour. Moreover, they had progressed very far in more intellectual directions, and for verbiage, niceties of language, skill in dialectics, in detecting the weak points of an argument, in making use of a technical flaw to establish a weak defence, for giving an answer which appears satisfactory at the moment but will presently be found to be no answer at all, and, in general, for concealing information and at the same time giving the listener the idea that they are conveying it, some of these men are hard to beat. Even long experience and a knowledge of the Haussa language, which they all talk, will not always save a political officer from being outwitted. Nor can it but be admitted that many possess real statecraft, courage and promptitude in action, though it is in the latter quality that they are liable to fail.

Travelling further South, leaving the area conquered before our arrival by the Filane and by the Kanuri from Bornu, we emerge from the plains and enter broken country. Sometimes, as in the case of the area to the North of the Benue river, we find large granite ranges with peaks 6,000ft. in height above the level of the sea. Here the natives are very different. Semitic blood is no longer evident and the type approaches rather towards that of the negro, but, as yet, they are not by any means pure negroes, but rather negroid. Probably the home of the Bantu race is to be found just to the North of the Benue on the Bauchi plateau, where natives very like the Basutos, with ponies which they ride barebacked over every kind of stony hilly ground, are to be found. These people successfully resisted the Muslim from the North finding refuge in their hills and the areas of forest which clothe the banks of the rivers and streams. For the most part they are extremely, almost absolutely, primitive, except in respect to their agriculture, which is excellent.

His body smeared with red clay, his hair matted and stiffened with grease; a few brass ornaments at his elbows, wrists, knees and ankles; probably a pair of iron greaves on his legs, polished like silver by the grasses as he strides along; with a necklace of bright blue or red beads and earrings of the same; a girdle with a knife hung on it, a quiver on his shoulder and a bow in his hand and with nothing at all resembling clothes on his body, unless it be a goatskin hung over his buttocks giving him the appearance of having a tail; his highly developed muscles forming a series of rippling convex curves all over his burly form, a good specimen of the natives of these parts fills in reality the frame of the ideal savage of the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- The Historical Background to Lugard’s Occupation of Northern Nigeria

- Preface to the First Edition

- Table of Contents

- Chapter I. Introduction

- Chapter II. Ponderation.—The Relations Existing Between Dominant and Dependent Races. Quo Vadis?

- Chapter III. Ponderation.—Direct versus Indirect Rule, with Special Reference to Nigerian Practice

- Chapter IV. Ponderation.—Indirect Rule and What It Means. A Plea for a Settled Policy in Nigeria

- Chapter V. Pochade.—The Resident’s Dilemma

- Chapter VI. Pochade.—The Anatomy of Lying

- Chapter VII. Pochade.—Eggs, Fowls, Guinea-Corn and Horses

- Chapter VIII. Ponderation.—Land Tenure

- Chapter IX. Ponderation.—Drink

- Chapter X. Ponderation.—Administration of Justice

- Chapter XI. Ponderation.—Direct and Indirect Taxation of Natives

- Chapter XII. Ponderation.—Missionaries, Education and Slavery

- Chapter XIII. Pochade—.A Mass of Pottery

- Chapter XIV. Parthian Arrows