eBook - ePub

The Academic Profession

The Professoriate in Crisis

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Academic Profession

The Professoriate in Crisis

About this book

The purpose of this series is to bring together the main currents in today's higher education and examine such crucial issues as the changing nature of education in the U.S., the considerable adjustment demanded of institutions, administrators, the faculty; the role of Catholic education; the remarkable growth of higher education in Latin America, contemporary educational concerns in Europe, and more. Among the many specific questions examined in individual articles re: Is it true that women are subtly changing the academic profession? How is power concentrated in academic organizations? How successful are Latin America's private universities? What is the correlation between higher education and employment in Spain? Is minority graduate education in the U.S. producing the desired results?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Academic Profession by Martin J. Finkelstein, Philip G. Altbach, Martin J. Finkelstein,Philip G. Altbach in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralNew Faculty as Teachers

In the midst of growing concerns for college teaching [1] we produce more and more useful advice about ways to improve instruction [8]. Yet, we know almost nothing about how (and how quickly) professors establish their teaching styles. And, it follows, we too rarely consider strategies for dealing with their teaching in its formative stages.

This article depicts the experience of new faculty as teachers over periods of one and two years and across two large campuses. It shows a surprisingly slow pattern of establishing comfort and student approval, of moving beyond defensive strategies including overpreparation of lecture content, and of looking for supports in improving teaching. The few prior efforts at observing new faculty have been enlightening but limited to smaller groups, to fewer observations, or to nonteaching activities [3, 5, 6].

The aim of this study, though, is not simply to document the teaching experiences of new faculty but to answer four related questions. First, do initial teaching patterns, adaptive and maladaptive, tend to persist? Second, what can we learn from the experiences of new faculty who master teaching quickly and enjoyably? Third, how does success in teaching correspond to prowess in areas including the establishment of collegial supports and of outputs in scholarly writing? And, fourth, how do initial teaching experiences compare at a “teaching” (comprehensive) and at a “research” (doctoral) campus?

Methods

The four cohorts of new faculty described here came from two campuses, (1) a comprehensive university with some thirty-five thousand students and about one thousand faculty and (2) a doctoral campus with some fifteen thousand students and some one thousand faculty. Both campuses hired similar numbers of new tenure-track faculty during the study years of 1985 to 1990, from fifty to seventy per year.

Cohorts

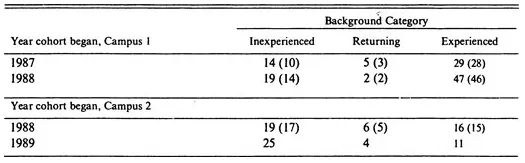

Table 1 shows the composition of the four cohorts, two of them from the former campus and two of them from the latter campus. Cohorts 2 and 3 overlapped as the author transferred his faculty development programs from the first campus to the second during 1988–89.

TABLE 1

Distribution of Background Types of Interviewees across Cohorts for Both Campuses (number of participants during second years are shown parenthetically)

At Campus 1, all but one to three new faculty per cohort volunteered for interviews conducted in their offices over successive semesters. The few individuals who did not participate were inaccessible because of their commitments off campus. At Campus 2, all but twelve to fifteen new faculty per cohort volunteered to participate in the same format of interviews. Campus 2, much less publicly committed to teaching than Campus 1, differed most obviously in the influence of department chairpeople; at Campus 2 (but never at Campus 1), five of some forty chairs advised their new faculty not to participate in a program that might interfere with research productivity.

In most other ways the two groups of new faculty were alike. They came to campus with similar levels of scholarly productivity, of teaching experience, and of doctoral credentials from prestigious universities. New faculty at both campuses also declared an interest in teaching well and in establishing themselves as visible members of their disciplines. However, newcomers at Campus 1 differed in that they expressed an interest in avoiding the pressures for publication existing at research universities such as Campus 2.

At both study campuses, a critical distinction emerged between types of new faculty. They differentiated themselves as (a) inexperienced (with less than two years beyond the doctorate, (b) returning (from careers outside academe and/or teaching), and (c) experienced (including full-time teaching at another campus).

The most obvious difference between the two campuses was teaching load. Campus 1 had an official load of twelve classroom hours a week (that is, four separate courses per semester). Most of its new hires received three hours of release time in year 1 on campus; thereafter, only a minority of successful applicants who demonstrated productive beginnings continued to receive reduced teaching loads. Campus 2 had a two-course (or six hours a week) load except for some humanities faculty who carried three courses. The majority of new faculty at Campus 2 in the science areas had teaching loads of one course or less for their first year or two on campus.

The key faculty under study here are the inexperienced newcomers and returning newcomers; experienced new faculty serve as comparisons. Most inexperienced and returning new faculty in this sample had minimal experience as classroom teachers during graduate school (N= 17 at Campus 1 and N = 12 at Campus 2 taught their own classes as graduate students). Fewer still reported any systematic training including teaching practica (N = 8 at Campus 1; N = 5 at Campus 2).

Interview Formats

The interview format resembles that used in prior research with new faculty by a variety of researchers [7]; copies can be obtained from the author. Each participant in this study was interviewed during successive semesters. Essentially, I asked new faculty about their experiences and plans as teachers, colleagues, and scholarly writers. These visits to new faculty, however, consisted of much more than preplanned interviewing. Interactions usually lasted one hour, often longer, always in informal fashion with prods for open-ended answers beyond responses to structured questions. Thus, except for replies to set questions, individuals chose what to emphasize and develop.

Participants were recruited by means of phone calls in which they were asked to give an hour of their time for a confidential interview about their experience as a new faculty member on campus. Where new faculty expressed ambivalence about participating, the author visited them during their posted office hours to repeat the request. This modicum of social pressure was sufficient to enlist almost all faculty who would otherwise not have participated; the result was a representative sample of individuals who volunteered and who, invariably, indicated satisfaction in having done so. As indicated above, this strategy worked except in some cases at Campus 2 where chairs (distributed across campus) had cautioned their new faculty not to participate.

A critical condition for all new faculty was the assurance that I would not relate information about the participation or answers of individuals to anyone. Administrators, who routinely asked about the involvement or responses of individual faculty, were given the kinds of generalized and/or anonymous results reported here.

My own role in this study was multifaceted and reflects my training, first as an ethologist and then as a psychotherapist; that is, I interacted with new faculty as an observer, researcher, helper, and colleague. I began initial interviews by explaining this complexity of interactive stances as part of explaining the project’s purpose. No one expressed discomfort with my multifaceted role or with the prospect of waiting to learn the results of repeated interviews in manuscripts like this one.

Results

Interview formats produced both qualitative and quantitative results. Interviewees responded to requests to rate experiences on 10-point Likert scales (for example, rate your recent comfort in the classroom), to specify experiences including teaching practices (for example, number of colleagues with whom they discussed teaching), and to elaborate on quantitative answers (for example, “how do you suppose students would describe you as a teacher?”).

Analysis of these interviews is presented in terms of successive semesters on campus. Within each semester (for example, the first semester on campus), data are presented as a conglomerate of all cohorts studied; then, contrasts are drawn between backgrounds (as inexperienced, returning, and experienced), and between campuses. Where appropriate, individualistic patterns of new faculty are described to give a sense of how new faculty (1) experienced problems and supports as teachers, (2) showed ready promise as successes or as failures at teaching, and (3) responded to opportunities for help as teachers.

First Semester

Initial contacts with new faculty at orientation workshops (before the onset of formal interviews) revealed various common concerns. Because both campuses required publication for tenure, newcomers supposed that they would feel more pressured to write than to do anything else during coming semesters; they worried that teaching would suffer in the process. No one at orientation expressed concerns about social supports; in the exuberance of meeting other new faculty, campuses seemed easy places to make friends. Moreover, new faculty just arriving on campus often reaffirmed their attraction to academe as a place where autonomy is highly valued (as in this typical comment during orientation by an inexperienced new faculty member at Campus 1):

I’m not sure that I need this sort of thing [that is the orientation day]. I have people I can rely on back at———if I need them, but I think I know what I need to do. [In response to my question about whether she would be interested in having a mentor on campus?] No, I think I am too busy for that … and I’m not sure what such a person could tell me. That’s why I decided to become a professor; I like to have good people around me but I prefer to manage on my own.

By the midpoint of the first semester, when interviews were well underway, two surprising realities had set in. First, a lack of collegial support and of intellectual stimulation dominated complaints. Second, investments in lecture preparation dominated workweeks. Writing and other things that “could wait” were put aside until new faculty had time and energy left over from teaching.

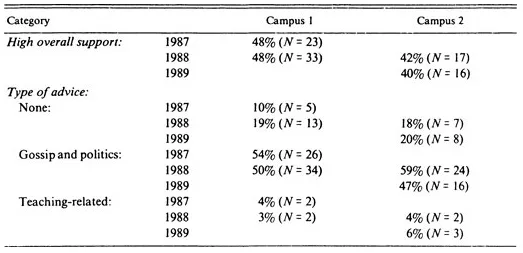

Collegial support. One specification of new faculty’s experience can be seen in analyses of reported collegial help in terms of advice about teaching (see table 2). Three results stand out. First, general levels of collegial support evidenced as advice were anything but universal; senior faculty were unlikely to say much beyond initial small talk. Second, most of what they did say that could have been credited as informative and supportive tended to be far more gossipy than new faculty would have preferred. And third, of all the kinds of advice and support, counsel about teaching was least often reported (table 2). This comment from an inexperienced newcomer at Campus 1 was normative:

No, no one has said much about teaching. Mostly, I’ve been warned about colleagues to avoid. A lot of it is gossip and complaining. I can only think of two specific things that have been said about teaching here. One is how bad the students are … about how unprepared and unmotivated they are. The other one, that maybe two people mentioned, was a warning about the need to set clear rules and punishments on the first day of class. All in all, I’m pretty disappointed with the help I’ve gotten.

TABLE 2

Percentage of New Faculty Reporting High Overall Levels and Specific Kinds of Collegial Support in Terms of Advice Offered by Senior Colleagues

This inattention to teaching surprised new faculty at both campuses. Inexperienced and returning faculty were not confident that they knew how to teach (although their senior colleagues seemed to assume that they did). Almost all new faculty felt that they should have gotten more concrete help such as syllabi from courses that preceded theirs. And, the majority of new faculty at both campuses reported that they had not been given appropriate strategies for coping with difficult students, especially those who disrupted classes or who might complain to departmental chairs. (At each campus, rumors spread quickly about new faculty who suffered embarrassment and other punishments as a result of such complaints).

Another way of documenting inattention to teaching can be seen in a single datum: Less than 5 percent of new faculty in their first semesters at either campus could identify any sort of social network for discussing teaching. Moreover, no new faculty were in departments where colleagues met occasionally to discuss teaching (in ways akin to departmental discussions about, say, the scholarly literature).

These questions about support produced another surprise. At both campuses, nurturance was no greater for inexperienced and returning faculty than for experienced newcomers, despite the seemingly greater need of the former. At Campus 2, curiously, experienced new faculty reported receiving by far the most useful advice and encouragement; this was part of a general pattern where already accomplished professors were welcomed by their new colleagues.

When I asked new faculty about what sort of help they needed most as teachers, the answer was nearly universal: they imagined that the hardest tasks would be learning the appropriate level of lecture difficulty for students. The follow-up question, about how senior faculty could provide such help, produced a hint about why new faculty were passive in soliciting assistance. That is, new faculty could not imagine how anything short of direct classroom experience could provide the answer they needed.

Another question asked for specific plans to coteach. New faculty’s plans (12 percent and 20 percent intentions to coteach for the two cohorts at Campus 1; 8 percent and 4 percent at Campus 2) and the results of those plan...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Volume Introduction

- I. Historical Context

- II. The Structure of Academic Careers

- III. Academic Culture and Socialization

- IV. Rewards and the Academic Marketplace

- V. Faculty at Work Teaching, Research, and Service

- Acknkowledgments