![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

In 1991 we wrote a book entitled Mountain World in Danger (Nilsson and Pitt, 1991) which drew attention to the potentially damaging effects of climate change on the cryosphere, the mountain and snow regions. This book is in many senses a complement to Mountain World in Danger. The protection of the cryosphere, or any other part of the biosphere for that matter, requires protection of the atmosphere which is so deeply bound up with the other ecosystems on our planet. Such protection, even if the data are incomplete or uncertain, requires urgent precautionary action on many fronts – legal, educational, economic, political, and social. New kinds of activities and instruments are called for which will at once mobilize the necessary political will and popular will. One such new animal in the international jungle is the subject of this book, the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FC). The FC, despite an apparently conventional legalistic form, is much more than a law and maybe the most important instrument to emerge from the Earth Summit at Rio promoting (to use the buzzword) sustainable development.

1.1 Purposes

The purpose of this book is to explain in plain language what the Framework Convention on Climate Change says and how it may work amid many difficulties. The FC is an international environmental treaty signed by leaders from 155 (now 166) countries and the European Community at the Earth Summit, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992. At the time of this writing (October 1993) 36 countries had ratified the FC. When 50 countries ratify the treaty it enters into force; this should happen before the end of 1993. The FC seeks from the Parties to the Convention commitments that would limit the causes and respond to the effects of climate change as well as provide a framework that would facilitate policies. The FC is concerned with much more than the environment. The central problem of global warming reflects the energy and economic policies of all countries and affects every person. In many senses then the FC is central to the future of the planet.

This book is intended for all those who seek to understand the policy implications of the climate-change problem and to find relevant responses. It may be useful for those who are involved in implementing the FC, at whatever level, whether in government or NGOs. Though our purpose is to present the essential points rather than details, it is hoped that the guide will be useful for educating, for training, for raising public awareness, and generally for communicating the messages about climate change. As an international treaty the FC is framed in conventional language which has been further convoluted by unprecedentedly long and tortuous negotiations. The book seeks to explore and explain the meanings which lie in or behind the Articles. It is hoped that this will assist the vast majority who would not normally read a treaty or who are bemused by the maze of sometimes obscure or opaque language.

We would like to make it clear that this book is not about the scientific data which are treated elsewhere (Nilsson and Pitt, 1991), nor about the detail of policy options, nor is it a legal treatise. Rather we are concerned with the evolution and nature of the FC in a political milieu. We are particularly interested in evaluating the international interface between the FC and a variety of politico-economic forces.

1.2 Greenhouse Problems

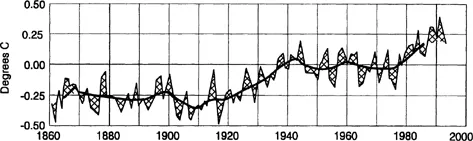

The FC has emerged as a response, at the highest international level, to what has been seen by scientists as a critical environmental problem. A strong lobby claims that never before in human history has there been a prospect of such an apparently rapid change in the planet’s climate (Figure 1.1), even if the number of critics and doubters is increasing, as more uncertain and contradictory evidence rolls in.

The planet is surrounded by an atmosphere which regulates the temperature. Naturally occurring gases shield the earth allowing in warming radiation from the sun but preventing much of the infrared reflection from escaping. However, scientists have detected an “enhanced” greenhouse effect created by additions in gas concentrations produced by humans, particularly since the industrial revolution. Not only has industrialization created a great increase in pollution leading to the acidification of soils, water, and forests, but it has also accelerated the natural warming process.

The most important greenhouse gas (about 56 percent) is CO2, mainly a byproduct of burning fossil fuels such as oil and coal. Normally absorbed in the oceans and forests, this gas has increased dramatically as the natural sinks are unable to cope and as the use of energy increases exponentially. This is not necessarily a new phenomenon. The analysis of trapped bubbles of CO2 in the ice cores has revealed that over millions of years rises in CO2 are directly associated with temperature increases.

By the early 1990s the majority of scientists working at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) agreed that a doubling of CO2 was likely to take place within 50 or 60 years and that there would be a consequent temperature rise of between 1.5°C and 4.5°C (IPCC, 1990, 1992a), assuming either “business as usual” policies or relatively mild measures such as halting deforestation, using natural gas, and encouraging energy conservation. The “doubling” effect was used to give a quantitative benchmark against which other statistics could be measured. The CO2 rise, however, would not necessarily stop at doubling. Even with minimal population growth, there are estimates that concentrations that are eight times higher than today’s might be found in 200 years with temperatures increasing 10°C or more. This regime would be as hot as any in the planet’s recent history including when practically all the ice melted and most of the world was water. Carbon dioxide represents about half of the greenhouse gases, but methane may also be a very important contributor (about 14 percent) since warming is not a simple correlation of gas prevalence and greenhouse effect. Methane emissions could increase as rapidly as population growth, since they are a product of agricultural development. As warming proceeds even more methane would be released from the melting of the permafrost and oceanic sources.

The doubling of CO2 and the associated temperature rise could produce major effects. As the ice melts and thermal expansion increases in the oceans, sea levels could rise drowning low islands and coastal areas including major cities. Hydrological systems would be disrupted as rainfall patterns change. Drought and floods would become common, the latter increased by the prevalence of huge storms in the more unstable, warmer air. The dryness would accentuate the decline of forests, which act as major sinks mopping up CO2 and the greenhouse gases. Regions of water deficit would lead to declines in agricultural productivity (Parry et al., 1988); indeed vast tracts of the planet are already too dry for cultivation without irrigation. The fauna and flora are particularly threatened in several fragile ecosystems, including islands, mountains, the cryosphere, coastal areas, wetlands, and forests.

Some of the pollutants – the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – contributing to greenhouse gases have also created holes in the greenhouse cover through depletion of high level ozone. The ozone layer protects the earth from particularly dangerous radiation which may affect the sustainability of life processes. Human health, the productivity of agriculture, and the effectiveness of important greenhouse sinks including oceanic phytoplankton may all be adversely affected by these atmospheric changes. A vicious cycle of global warming in the lower atmosphere may trigger major ozone destruction above (Nature, 1992, Vol. 360, No. 6401).

There are also fears that at some point the changes in temperature would introduce sudden catastrophes. The melting and breakup of the West Antarctica ice sheet could cause sudden rises in sea level as happened in the rapid breakup of the ice sheets 10,000 years ago. New interactions between hot and cold air and water could suddenly shift precipitation belts or change ocean currents.

Feedback cooling effects may also pose problems. For example, the emissions themselves and the warmer instabilities they engender, as well as volcanic eruptions, produce an increase in cloud cover which tends to damp down temperature rises. Sudden cold snaps and snowstorms have had disastrous effects especially on agriculture in North America in recent years. Moreover, clouds may be so impregnated with acidity and toxic substances that precipitation poisons soils, watercourses, and forests. Recent evidence (Nature 15 July 1993) from ice cores shows cold snaps in the last great interglacial over 100,000 years ago. These snaps flipped on for short periods perhaps because of ocean current switches.

There are many uncertainties (WWF, 1992). Knowledge is incomplete about the links in the enhanced greenhouse chain and therefore about future projections. There are two types of uncertainty: first, imperfect information about the science of the physical processes; second, difficulties in predicting future trends in the global economy (population growth, GNP, technological developments, etc.). The scientific uncertainty relates to the conversion and coupling of emission rates concentrations, climate changes and impacts, both regionally and globally. Given the huge effort by scientists and the improvement in computer resources this situation should improve, and the present rather broad estimate band of a 1.5°C–4.5°C temperature rise with doubling of CO2 should narrow. Despite problems with the evidence, the consensus is that precautionary measures are needed.

1.3 Solutions

If there is a measure of agreement on the need to tackle the problem, the means to counteract warming are much more contentious. Here the complex feedback effects and great uncertainties interact with different points of view on appropriate levels of energy use, degrees of intervention, and whether the rate of increase of CO2 should be slowed down by abatement, restricting emissions, encouraging conservation, alternative energy sources, greater efficiency, etc.

Three possible strategies can be identified, even if not mutually exclusive, each involving a different level of intervention. The least interventionist strategy is “passive adaptation” (as discussed in WWF, 1992, among others). Here no explicit action on the greenhouse problem is taken and society simply adapts to changes as they occur, unless and until the scientific uncertainties are narrowed. This strategy presumes that changes will occur (as historically) slow enough to allow adaptations such as migration, switching resources to protect against sea-level rises, and so on. Since there is great uncertainty, the “passive” argument implies that it may hardly be worth huge expenses to protect against possible risk (Pearce in OECD, 1991).

Some scenarios, however, predict more rapid, and even catastrophic changes. Even with a huge 75 percent cut in emissions, CO2 concentrations would stay much the same up to the year 2100. Passive adaptation does permit individuals or countries to make choices and is therefore favored by market-oriented economists and mercantilist politicians alike. The problem is that, although self-interested actions may sometimes be more effective than laws or education, there is no certainty that such actions will be well guided and have a cumulative benefit for the global environment or society. A more cogent reply to the passive argument is that if nothing is done the costs will rise astronomically and that environmental action to reduce pollution has other benefits such as decreasing wasteful use of energy, resources, and so on.

Another alternative is to reduce emissions and enhance sinks. The sinks that absorb the CO2 can be improved, e.g., by reducing deforestation and promoting reforestation. Complex fiscal and legal mechanisms have been proposed including carbon taxes and emission trading. There has been great debate about the targets for such policies and the level of emission cuts. Achieving high levels is difficult not least because of the long life expectancy of some existing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Although there is a fear that high targets would restrict economic growth, a strong case has been made that there would be benefits from renewable energies in the short term as well as long term. A third option is “active” adaptation, by preparing flood defenses, relocating communities, investing in climate-resistant crops, etc. Adaptation has the advantage of being cheaper than emission reduction and more effective than doing nothing.

Developing countries are particularly concerned that abatement efforts could damage development prospects. Total greenhouse emissions from the South are about one-half those of the North, and fossil CO2 emissions from the South are only a quarter of the North’s, though they are growing rapidly. In 1988, the North consumed three-quarters of all energy though having only one-quarter of the population; overall per capita consumption was 10 times that of Southern Hemisphere countries, and in extreme cases 40 times or more. Schemes for a trade in emissions and taxes have been proposed whereby developing countries may still achieve development targets by selling off their proportional rights in energy consumption. But the total situation of the South must be taken into account. Alongside, or underlying, the climatic changes are social, economic, and political crises. The United Nations has produced figures that the absolute poor number over 1 billion, perhaps a quarter of the world’s population, and the numbers are increasing. These are people deprived of even the minimal standards of health, nutrition, education, and life opportunities. The environmental crisis, especially desertification, adds significantly to the pressures on the poor and makes more likely devastating wars where nations compete for ever-scarcer resources, particularly water (Homer-Dixon et al., 1993). The poor nations have very few resources to devote to economic development or to mitigate climate-change effects.

Control of sources has been thoroughly discussed but the same cannot be said for the opposite side of the coin – sink enhancement. The media have focused on tropical deforestation, although recent evidence shows that deforestation in other regions may be equally significant. One recent IIASA study (Shvidenko et al., 1993) has described the poor state of the Siberian forests, which may sequester as much as half of the Amazon load. While stopping deforestation and promoting better forest management may be necessary, it is not sufficient. There are estimates that an area the size of Western Europe may need to be planted to provide an adequate global sink; a project of this size would surely require a mass planting movement like Roosevelt’s depression years’ tree army, which had more men under orders than the military army during World War II.

1.4 The Role of the Framework Convention

Although all the scientific evidence has not been collected or evaluated nor all the contentious policy issues resolved, a majority of expert opinion has convinced political leaders that there is an urgent need for precautionary action to prevent a future climate-change crisis and to mitigate its effects. The FC has been a major element in the response in the international community. The FC (see full text in the Annex) is a unique document. The FC was distilled from a huge mass of complex data and at the same time was the product of negotiations among virtually all the nations of the world, a process which also involved NGOs. Although the focus was on climate change, the issue was no less than the future of energy itself. Thus the FC may become a central instrument for the economic, political, social, and ecological developments for the planet, though there have been important criticisms – especially that the FC is too vague and lacks adequate targets.

Those who champion the FC argue that, because the energy problematique is extremely complex and there are many different interpretations, demands, and political pressures, the FC lays out only a broad framework. Because the object of negotiations was to reach a consensus and not to be unduly delayed, if not derailed, by conflicts, the FC reflects the common minimum level of agreement. Nonetheless the FC establishes parameters within which energy policies must be formulated but is at the same time flexible enough to accommodate more restrictions should the need arise. The FC is both a legally binding treaty on nations and an educational instrument through which the most important scientific messages about climate change are transmitted.

Last, and by no means least, the FC opens the way for climate aid and intense international cooperation. The contributions required from the North, from the South, and from countries in transition to a market economy are quite different. Therefore, not only must policies articulate global ecological imperatives, but they must also reflect development inequities and sociocultural differences. In other words, the South requires more access to energy (especially electrification) to be lifted from poverty, and will require additional transfers of resources and technology to ensure that this energy is as environmentally friendly as possible.

1.5 International Law and the Environment

The FC is part of a new thrust in international law concerned with the environment. Traditionally international law has been concerned with negotiations between sovereign states. Because climate change has a global impact and because there are, in the complex modern world, many power holders, the FC must provide a framework not only for states but also for multinational corporations (who now control more wealth than nations) and many other nongovernmental organizations. The new international law not only provides a structure in which to hold negotiations. It also creates obligations for the multifarious power holders and a means of holding them into account. Cameron (1993) has written that laws, like the FC, are “ideals” whose purpose “is to guide, exhort, obligate and persuade human behavior towards protection ... that is altered and adjusted by political morality at any particular time in history.” Thus instruments like the FC directly affect individua...