![]()

one

Teacher learning

The building blocks

Phil will never forget his first driving lesson. His instructor, Len, was a reassuring figure: calm, soft-spoken and never in a rush. Len’s car was an old Renault with super soft suspension and a faint smell of lemon air freshener.

Stepping through the driver’s door into that seat was an odd experience. Everything felt familiar after the seventeen years Phil had spent as a passenger, and yet everything was also very new. First there was the physical closeness of all the controls, the three pedals, the wheel and gear stick. But then there was the sensation of just looking at the road from a new perspective, clutching the keys in his hand with a sense of anticipation.

Phil remembers Len looking at him and smiling: ‘We won’t go far unless you put the key in the ignition, you know.’ Okay, so this was actually happening!

Len asked Phil to push the accelerator slightly to get a feel for it, then to press the clutch and move into first gear. He explained biting point, asking Phil to gently release the clutch and gently press the accelerator. Obviously, Phil immediately stalled.

Len chuckled and told him not to worry. On the second go he managed it, and then released the hand brake. Excitement and horror – they were moving!

Suddenly, instructions were coming faster. Look in the rear mirror, look in the side mirror, use the indicator, move your foot to the brake, change gear, look over your shoulder, keep both hands on the steering wheel, be aware of that car. Everything started happening at once. Everything was unfamiliar. Phil felt overwhelmed with all the jobs and forgot the clutch. They stalled.

Thump.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Len, ‘you’ll get familiar. Let’s try again.’

***

Phil’s first driving lesson is a great reminder of what a new teacher is going through. Every teacher has spent many years in a classroom before they begin the job, but never as the person in charge. Things are both familiar and unfamiliar. Everyone brings baggage from their schooldays, but also must come to terms with being in charge of thirty children or young adults, smoothly directing the lesson, watching the timing, giving feedback, constantly scanning the room, maintaining self-awareness, operating electronic systems, locating and distributing books, and so many other things.

The fact that we can be both experienced and inexperienced at the same time is just one of the reasons that teacher learning is a complex process.

A model of learning and remembering

What’s actually going on when you learn something new? Sweller (1988)1 suggested that learning is a process of changing what’s stored in your long-term memory. It involves gradually moving along a scale from novice to expert.

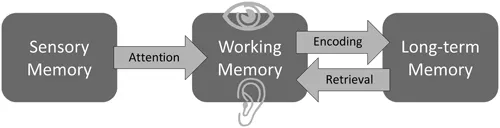

Let’s use a very simplified model of the learning process, based on the work of Atkinson and Shiffrin (1968)2 and Baddeley and Hitch (1974)3 (see Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 A simplified model of memory and learning.

In this model we’ve got a few key elements.

Sensory memory is a super short-term memory. It maintains an impression of everything you have just heard, seen, tasted, smelled or felt.

Attention is the process of focusing on certain sensations that are in the sensory memory. If you think about the little finger on your right hand then you will be aware of what it is touching, how warm it is, whether it feels uncomfortable or not.

Up until you thought about it, you probably hadn’t been aware of those sensations. But it is possible to deliberately direct your attention, thereby ignoring other sensations.

Attention is not always deliberately directed. If you step on a sharp stone, then you suddenly become aware of your feet. If you are working on a piece of writing, then you can sometimes become distracted by perceived hunger, thirst, tiredness, threat, etc. – i.e. the sorts of things that we’ve evolved to pay attention to in order to help us survive.

In that first driving lesson, Len was helping direct attention to the most relevant and important sensations around him.

In the development of teaching, we want to help teachers stay focused on the most relevant sensations and information to avoid confusion and distraction.

Working memory is where we temporarily store sensations or ideas – it’s like a temporary jotting pad. It has very limited capacity; we can only store a few elements at once. However, there are thought to be two distinct channels within working memory: the first is sounds and words, the second is images and shapes. The two channels work in parallel. We can learn more when the information coming into both channels is complementary. We refer to this in Chapter Six when exploring effective delivery of expertise.

Even though working memory is very limited, we often ‘cheat’ the limits by remembering a block of information as a single chunk. E.g. the word ‘moon’ doesn’t require four spaces, one for each letter, M – O – O – N, as we are able to quickly match the pattern of the word to our long-term memory of the word ‘moon’ and just keep the memory of the whole word in working memory.

The more knowledge and memories we hold in our heads, the more we can take complex sensations and chunk them, ‘cheating’ our normal limits and enabling us to progress to more complex overall thinking and increase our general fluency.

However, where we don’t have enough experience or knowledge then we cannot chunk, and our working memory can be overloaded. This is what the inexperienced driver experiences during that first driving lesson – they are unable to group together lots of familiar sensations as ‘driving’ as nothing is familiar. It’s impossible to hold everything in their working memory at the same time.

In teacher development we often see situations where teachers’ working memory is overloaded: when attempting to operate a new, unfamiliar piece of software during a challenging class; or when a beginner teacher attempts to combine classroom management with explanation and questioning.

Encoding is the process of turning short-term memories into long-term ones. Not all memories are encoded equally. The strength of the memory can be affected by many factors, including:

■ which sensations or ideas seem more relevant to the task at hand;

■ the intensity of our emotion at the time; and

■ how hard we’ve worked at making meaning.

Interestingly, an explicit intention to try and learn something appears to have no impact on how effectively we encode it. What matters is the process of thinking used, the environment around us and where we are focusing our attention.

A series of driving lessons accompanied by regular practice should encode the sensations and experiences of driving into long-term memory.

In working with inexperienced teachers, we want them to encode a huge amount of knowledge and skill while engaging in the stressful activity of directing a whole class of students. They are naturally drawn to pay attention to the things that are most important to them, but these are not necessarily the stimuli that would be most important to an expert.

Experienced teachers sometimes must interrupt their automatic process of making sense of what they are seeing or else they end up encoding the familiar and filtering out the unfamiliar. This is what makes learning something unfamiliar so difficult – new ideas get harder to assimilate and existing thinking becomes increasingly entrenched. We also need to repeatedly encounter new or improved ideas so that they can be at least as strongly encoded as old habits and thinking. This is probably one of the reasons that effective teacher development almost always requires a sustained cycle of encountering ideas – one encounter appears to be unlikely to encode a suitably strong new pattern of thinking.

Retrieval is the process of accessing memories from long-term memory. It is mainly a pattern-matching process where the contents of working memory are matched against long-term memories to find a best fit.

Interestingly, remembering something strengthens and modifies the original memory. For example, if you retrieve your memory of oranges while also thinking about an unpleasant taste, then the original memory of oranges is now modified to be more associated with an unpleasant taste. Similarly, if a teacher on repeating a successful lesson finds that it now goes wrong, that teacher may then make negative associations with that content or class.

Each time you practise driving a car, you are retrieving the memory of the various sensations and tasks. Repeated practice means repeated retrieval, and this means stronger memories.

The way that retrieval works is a challenge when a teacher is trying to change the way they think about something. Every time the old, out-dated memory is triggered, it can be strengthened. It’s hard to embed new ways of thinking, and hard to change old ones.

The implications

We can use this model to help understand that learning is a continuum. It is very different to engage in a task when we have very few relevant memories than to engage in that same task when we have many relevant memories. More knowledge of, and experience in, a task allows us to move from being a novice to gaining greater expertise, although there is really no limit to this level of expertise – you can pretty much always become more expert.

Someone with more expertise …

… will be familiar with most of the situations or problems they face in a particular domain. For example, an expert quadratic equation-solver will recognise the vast majorit...