eBook - ePub

Class, Caste and Color

A Social and Economic History of the South African Western Cape

- 271 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume is the first general social and economic history of the Western Cape of South Africa. Until recently, this region had been largely neglected by historians because it does not occupy a central place in the national political economy. Wilmot G. James and Mary Simons argue that a great deal about modern South Africa has been shaped by the distinctive society and economy of the Western Cape. Its history also reveals striking parallels and contrasts with other regions of the African continent.The Western Cape is the only region of South Africa to have experienced slavery. In this sense, the Western Cape has historical traditions more akin to colonial slave societies of the Americas than to those of the rest of Africa. Moreover, in contrast to the rest of South Africa, a proletariat emerged in the Western Cape early in its history, at the start of the eighteenth century. There developed a much more stable and enduring system of class and labor relations. In the twentieth century, these became closely enmeshed with race and status. Racial paternalism and the close correlation between class, caste, and color have their historical roots in the Western Cape.The book is arranged thematically and explores the social and economic consequences of slavery and emancipation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Issues of economy and labor, such as economic underdevelopment in the Western Cape, the labor market, and trade-union organization in the twentieth century are examined. The authors also treat the role of the state in shaping Western Cape society. Class, Caste, and Color is not only a groundbreaking work in the study of South Africa, but provides an agenda for future researchers. It will be essential reading for historians, economists, and Africa area specialists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Class, Caste and Color by Wilmot James in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Historical Foundations

1Labour, land and livestock in the Western Cape during the eighteenth century : The Khoisan and the colonists

NIGEL PENN

At the beginning of the eighteenth century labour relations between the colonists and the Khoisan of the Western Cape were characterised by semi-cooperative symbiosis. By the end of the century however, the majority of the Khoisan in the area had been transformed into a class of wage labourers whose status was little better than that of slaves. The purpose of this chapter is to examine some of the features of Khoisan-colonial labour relations at different periods during the century and to provide details of specific relationships in order to illustrate the processes of transformation involved.

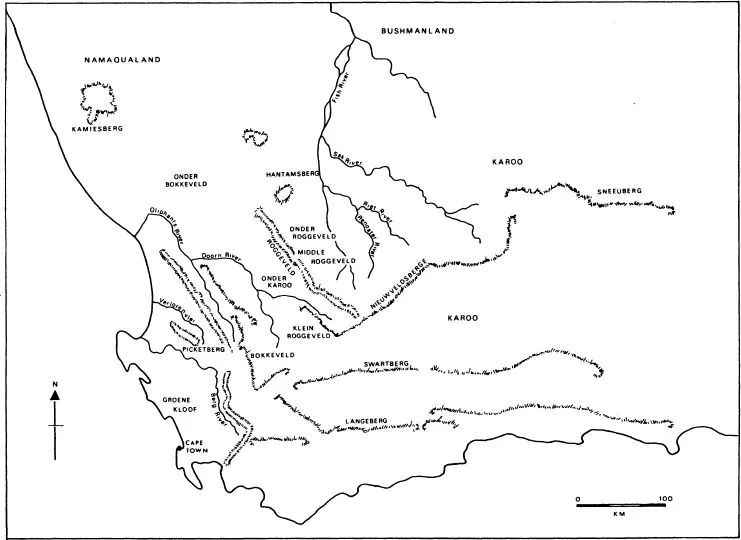

Broadly speaking, there are three major chronological divisions into which the eighteenth-century Western Cape may be divided: 1700–1740, 1740–1770, and 1770-C.1800. Each of these periods had certain distinctive features which influenced labour relations between colonists and Khoisan in different ways. It will be necessary to outline their characteristics in greater detail, but before doing so, it should be noted that this chapter makes a distinction between the south-western Cape and the Western Cape. It takes as its area of study the regions north of Paarl and south of Namaqualand, east of the Atlantic Ocean and west of the Roggeveld. This region, the present-day Western Cape, was for much of the eighteenth century the northern frontier zone of the Cape Colony and, as such, its labour history is intricately connected with frontier history. It should not therefore be regarded as a static, geographical area with precise boundaries, but rather as a zone of interaction whose boundaries were, until 1770, being constantly redefined by processes of colonial expansion.1 After 1770 a combination of military and environmental constraints prevented further colonial expansion north-east of the Roggeveld. Expansion to the north of the Olifants River and the Bokkeveld Mountains had been checked, though not altogether halted, by environmental considerations after 1750, and a few Trekboers had established themselves in Namaqualand by the 1750s. Namaqualand was, however, a distant, distinct and isolated part of the eighteenth-century Cape, being more truly north-western than western and, as such, outside the scope of this chapter.

What distinguished the Western Cape from the south-western Cape during the eighteenth century was that in the former region pastoral production was the dominant economic activity, whereas mixed agricultural production predominated in the latter region. This was partly due to climatic reasons, since the south-western Cape was better watered, but also due to the proximity or distance of the Cape Town market. The further away from Cape Town a farmer was, the more difficult and uneconomical it became to transport agricultural produce to market. Though meat could walk to market, and though there was a market for meat at Cape Town, one of the most powerful attractions of pastoral production was that a pastoralist could expect to attain a high degree of self-sufficiency for an initially low capital outlay.2 By issuing grazing licences north of the Berg River in the Land of Waveren (Tulbagh basin) in 1700, the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) initiated a new phase in colonial expansion since the growing population of whites now had prospects for an independent livelihood in the Cape interior. The shift to pastoralism meant that the system of land allocation in the Western Cape differed from that of the south-western Cape. Since pastoralists needed extensive areas of land which, if need be, they could vacate once the grazing deteriorated, the loan-farm system was adopted. Land was rented from the government rather than bought, as was the case with the freehold farms of the south-western Cape.

The consequence of this system of land allocation was that it encouraged the rapid dispersal of free burghers into the interior which, in turn, had incalculable effects on the economic, social and political development of both their own and the Khoisan societies. Not only did the Khoisan lose their livestock and land to the colonists, but they were also absorbed into colonial society as labourers. In this respect too, the Western Cape differed from the south-western Cape, for in the latter region slavery was the preferred form of labour. By the 1720s there were very few Khoisan to be found within a distance of fifty to sixty (Dutch) miles of Cape Town3 and it is to the Western Cape that we should turn if we wish to study the development of colonial attitudes towards the indigenous inhabitants.

There are thus a number of reasons why the eighteenth-century Western Cape was of great historical significance, and there is a very real sense in which the labour relations that evolved there may be regarded as being prototypical of subsequent South African racial attitudes. Whilst considerable attention has been given to the south-western Cape and the Eastern frontier, the Northern and Western Cape hinterland have, as far as historical research is concerned, slumbered in the ‘long quietude of the eighteenth century’.4 This neglect has been partly the result of contemporary perceptions: if the area is a backwater today, what must it have been like in the eighteenth century? The truth is that it was the crucible from which emerged many of the subsequent processes of South African history: details of the reactions which took place within it are therefore vital to an understanding of our past.

1700–1740

Before 1740 the major processes in operation in the Western Cape were those which are associated with an ‘open frontier’: that is, there was competition for the productive forces of land, livestock and labour.5 By 1740 this competition had been resolved, in favour of the white colonists, in an important sub-region of the Western Cape, namely the area west of the Bokkeveld and south of the Olifants and Doom rivers. After the successful conquest of this area and the crushing of Khoisan resistance, the colonists were able to continue their expansion in a north-easterly direction, across the Tanqua Karoo (or Onder-Karoo) to the Roggeveld. This advance had the effect of opening the frontier in the hinterland whilst it began to close west of the Bokkeveld. In this section however, we are concerned with the earliest period of the open frontier in the Western Cape.

The movement of colonial pastoralists, or Trekboers, into the Western Cape initiated competition between them and the Khoisan for land, grazing and water resources. To a large extent the history of the period 1700 to 1740 is simply an account of the processes whereby the Khoi were stripped of their livestock and denied access to grazing and water resources - unless they were prepared to work for the colonists. Such a process was not, however, instantaneous, nor did it proceed unresisted. The history of this resistance has been described elsewhere.6 It is necessary though to discuss the forces which drove some Khoisan to work for the colonists whilst others fled or resisted them.

The Khoisan societies of the Western Cape had already been seriously weakened by their earlier contacts with Dutch settlers in the seventeenth century.7 Warfare, cattle theft and enforced bartering had been visited upon them by the VOC for half a century before 1700. After 1700 their plight became worse since the Company opened the cattle trade with the Khoi to the colonists at the same time as it opened the Land of Waveren to white settlement. This suited the settlers, as it enabled them to build up their own flocks and herds, but it was disastrous for the Khoi. The methods by which the colonists increased their livestock holdings ranged from barter to outright robbery, but given the well-attested reluctance of the Khoi to part with their livestock, it is likely that robbery was the usual method employed. When Johannes Starrenberg, the landdrost of Stellenbosch, visited Verlore Vlei in 1705 with the intention of bartering trek-oxen from the local Khoi, he found that their cattle were few in number and mainly cows.

I asked them [the Khoi] how it happened that they had so little cattle, seeing that the Hon. Company had never bartered with them, whereas they informed me: that a certain Freeman, generally called Dronke Gerrit, was come to their kraal a few years previously, accompanied by others, and without any parley fired on it from all sides, chased out the Hottentots, set fire to their huts, and took away all their cattle, without their knowing for what reason since they had never harmed any of the Dutch. By this they lost everything they had, and were compelled to betake themselves to the Dutch living further out, and there steal cattle again, and if they could get anything, rob their own compatriots; and with these cattle they then ran off into the mountains and feasted on them until it was all finished, and then getting more, several times succeeding in this, from which they still have a few beasts today.8

Doubtless Dronke Gerrit was not the only colonist engaged in accumulating livestock before 1705. The figures for the increase in the livestock holdings of the colonists in general are instructive. In the eight years before the opening of the trade, their herds had grown by 3 712 and their flocks by 5 449; in the first years of free trade the corresponding figures for growth were 8 871 and 35 562.9 Intimations of the violence spawned by the opening of the trade reached the authorities as early as 1702 when the trade was temporarily banned and an enquiry was ordered into the number of trading expeditions which had taken place. The ban was however lifted in 1704.10 By 1705 the Khoi population of the Western Cape had been so badly affected by the open cattle trade that in a twelve day journey between the Berg River and the site of present-day Klawer, Starrenberg found only two homesteads which, though they contained twelve captains, had very little cattle. Starrenberg noted:

I have realised with regret how the whole country has been spoilt by the recent freedom of bartering, and the atrocities committed by the vagabonds…and so from men who sustained themselves quietly by cattle-breeding, living in peace and contentment divided under their chiefs and kraals, they have nearly all become Bushmen, hunters and brigands, dispersed everywhere between and in the mountains.11

Starrenberg's observations are of great interest for they draw attention not only to the processes by which the Khoi were becoming San, but also to the sparse population of the area. It is unlikely that the Western Cape had ever had a large population. Because of the mountainous nature of much of the terrain, the pre-colonial Khoi would have confined themselves to the plains around the Piketberg, the v/eis of the Sandveld and the valleys of the Olifants and Doom rivers. The evidence suggests that the area between the Berg River and Namaqualand was a sort of no-man's-land between the powerful Khoi groups of the south-western Cape and the Namaqua. The Guriqua, who were the permanent pastoralists of the area in pre-colonial times, emerge from the records as being a weak and motley amalgam of strandlopers (beachcombers), hunter-gatherers and offshoots from their more powerful Khoi neighbours.12 The Namaqua appear to have been the strongest of these in the seventeenth century and were encountered by the Dutch south of the Olifants River in 1661. It seems that they were accustomed to entering the region in summer or during droughts, but seldom ventured south of the Kamiesberg once they became aware of what contact with the colony entailed.13 There are occasional references in the records to Khoi kraals along the Olifants River and in the Bokkeveld and Roggeveld mountains. It is however clear that this presence was diluted by groups of people whom the colonists called ‘Bushmen’ - even though some of these groups kept livestock and were not simply hunter-gatherers.14

As the colonists consolidated their hold over the land, its grazing and resources, the chances of the Khoisan leading an independent existence diminished. One response to this situation was resistance, but increasingly, and for a variety of reasons, Khoisan began to enter the service of the Trekboers. Those who had lost their means of subsistence naturally had compelling reasons to become servants. Some Khoi, however, who had managed to retain livestock decided that they would benefit from the protection that an armed and mounted Trekboer could provide them against predators and the many stock thieves of the frontier zone. In exchange for this protection, or as a condition for their continued access to water and grazing, they began to perform labour services for the Dutch. By grazing and caring for the flocks and herds of their protectors, frequently alongside the remnants of their own flocks and herds, the Khoi did much to prolong their existence. We should note that apart from the demands for livestock by the Company and free burghers, there were large groups of escaped slaves, deserters and people who were described simply as ‘vagabonds’ who roamed the frontier zone of the Western Cape at this time, all of whom were a threat to Khoi livestock.15 Different groups of Khoisan did not scruple to steal the livestock of more fortunate Khoi, and in such circumstances it paid to have the protection of the local colonists. For instance in 1730, when some of the Khoi who worked on the farm of Hendrik Eksteen at Saldanha Bay had their cattle stolen from them by Khoisan, a commando of Company men recovered their livestock.16

The contracts which the Khoisan and the colonists entered into were not formalised in writing - a fact which had two important consequences. In the first place there is very little written evidence of such contracts, and in the second place, being oral, they were frequently broken by the parties involved. It was only when employers or employees saw fit to complain to the authorities about a breach of contract that the terms of service were reco...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction by Wilmot G. James and Mary Simons

- List of editors and contributors

- Part One: Historical Foundations

- Chapter 1. Labour, land and livestock in the Western Cape during the eighteenth century by Nigel Penn

- Chapter 2. The family and slavery at the Cape, 1680-1808 by Robert Shell

- Chapter 3. Adjusting to emancipation: Freed slaves and farmers in mid-nineteenth-century South-Western Cape by Nigel Worden

- Chapter 4. Structure and culture in pre-industrial Cape Town: A survey of knowledge and ignorance by Robert Ross

- Chapter 5. A “special tradition of multi-racialism”? Segregation in Cape Town in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by Vivian Bickford-Smith

- Chapter 6. Aspects of the rise of Afrikaner capital and Afrikaner nationalism in the Western Cape, 1870-1915 by Hermann Giliomee

- Part Two: Economy and Labour

- Chapter 7. The underdevelopment of the Western Cape, 1850-1900 by Alan Mabin

- Chapter 8. Artisans and trade unions in the Cape Town building industry, 1900-1924 by Pieter van Duin

- Chapter 9. Wolseley’s great strike by Richard Goode

- Chapter 10. The General Workers’ Union, 1973-1986 by Johann Maree

- Part Three: Politics and Society

- Chapter 11. Ideology and urban planning: Blueprints of a garrison city by Don Pinnock

- Chapter 12. Administrative politics and the coloured labour preference policy during the 1960s by Richard Humphries

- Chapter 13. Non-collaboration in the Western Cape by Neville Alexander 180

- Chapter 14. Local government restructuring in Greater Cape Town by Alison Todes, Vanessa Watson and Peter Wilkinson

- Chapter 15. ‘Action, comrades, action!’: The politics of youth-student resistance in the Western Cape, 1985 by Colin Bundy

- References

- Index