- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

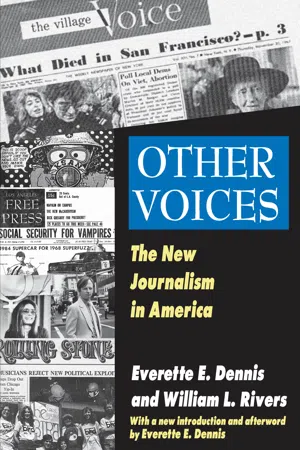

About this book

Conflicting journalistic voices that were raised in the past have become such a jumble that merely identifying them is difficult. Dennis and Rivers define, categorize, present, and examine the voices that contributed to what became known as "the new media" environment in the 1970s. This new journalism came about as a result of dissatisfaction with existing values and standards of the early 1960s style of journalism.The authors are comprehensive in their concerns, as reflected in the national scope presented. They cover developments in the major cities, on both coasts, in the Middle West and South in every major region of the United States. Most of the research required travel and interviews; all of it required reading almost endlessly and watching the video productions of journalists who built the structure of alternative television. Dennis and Rivers offer a representative view of forms and media, as well as the people who fashioned the new orientation.The authors claim that the wrangling over objective and interpretative reporting misses the main point, which is that neither is in close touch with reality. The best objective report may cover all surfaces of an event, the best interpretative report may explain all its meanings, but both are bloodless, a world away from the experience. Color, flavor, atmosphere, the ultimate human meaning all these, the new journalists contend, are far beyond the reach of traditional models of journalism. This is one of the central reasons for the emergence of different forms and practices in our time. This volume will help younger scholars understand the sources of quasi-journalistic practices extant today, including blogging and electronic-only publications.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Other Voices by Everette Dennis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Coalescing of Forces

…the First Amendment presupposed that right conclusions are more likely to be gathered out of a multitude of tongues than through any kind of authoritative selection.

—Judge Learned Hand,

in United States v. Associated Press

in United States v. Associated Press

In a time when old values are crumbling, when the miracle of advancing technology is suddenly seen to create as many problems as it solves, when disorder, turmoil, and violence become hallmarks of a nation—in such a time it cannot be surprising that the mass media, which are central to modern society, should feel the shock waves of change. It is not a mere coincidence that during the American upheaval of the last decade we begin to hear of something called the new journalism. It had vague beginnings in earlier times, but the turbulence of the 1960s gave it impetus. Like that turbulence, the new journalism is complicated, a wild mixture of styles, forms, and purposes that defies simple definitions so completely that it can be summarized only in the most general way: dissatisfaction with existing standards and values.

This book is being written to push beyond this generalization, to analyze a force that has already made a place for itself, a force that may alter journalism profoundly. To do so properly, we must admit and even emphasize that the new journalism is a misnomer. Critics are fond of pointing out that there is nothing very new about it. And, certainly one can find antecedents. The underground press, for example, may be considered a twentieth-century recurrence of the political pamphleteering in the Colonial period. Advocacy journalism is at least similar to the personal journalism of the last century. Alternative journalism may be little more than muckraking in new dress. The pollsters have been taking surveys for decades. Wasn’t Daniel Defoe writing the new nonfiction? And so on.

But to focus endless arguments on the validity of a term when the force it symbolizes is demonstrably real and important is semantic quibbling of an especially misleading kind. We use the term because it has caught on and become familiar. The important matter is that the several forms and practices of the new journalism, misnomer or not, have coalesced at this point in time. It is quite remarkable, after all, that practices centuries old in some cases and decades old in others should suddenly appear together today, be developed along new lines, force a place for themselves, and threaten a structure of reporting that only recently seemed strong and durable.

The chief question now is not to decide whether the new journalism has been given the right name but to define it properly and try to judge its impact. To make that clear, it is essential to sketch conventional practices.

Until the 1930s the average reporter wrote a formula. He tried to fashion a clear, concise, straight news story, starting with the who, what, when, where, and why of an event and proceeding toward the end by placing factual details in descending order of interest and importance—a device that enabled readers to grasp the essentials immediately and editors to cut stories from the bottom up. His job was to try to hold a mirror up to an event and show its surface. Explaining why it had occurred and what should be done about it were the missions of the editorial writers and the columnists. A few reporters, primarily those overseas and in Washington, had been given license to interpret the news and explain and clarify complex events. But almost everyone else was limited to straight news reporting.

With the advent of the New Deal, the old forms suddenly seemed inadequate. Washington correspondents of the time say they can fix on the exact moment when the old journalism failed utterly—the day in 1933 when the United States went off the gold standard. They appealed to the White House for help in reporting that baffling change, and a Federal Government economist was sent over to clarify the new facts of economic life. They tried to explain what he explained, without much success. Despite the failure, the correspondents had committed themselves to explanatory journalism, an abrupt departure from the superficialities of who-what-when-where-why reporting.

The increasing complexity of public affairs made it difficult to confine reporting to the straitjacket of unelaborated fact. Relaying exactly what a government official said was often misleading: even facts didn’t speak the truth. Moreover, reporters discovered that they were in effect running errands for the establishment and enshrining the status quo; the sources of news releases, press conferences, and official statements were usually men with position and power. Somewhat hesitantly, reporters like Paul Anderson and Marquis Childs of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and, a bit later, James Reston of the New York Times began to build the interpretative reporting structure that made its way back to city rooms everywhere.

The trend was fiercely debated. In the early sixties it split the top level of the great Louisville Courier-Journal. Editor Barry Bingham argued: “The need for interpretative reporting becomes more insistent week by week.” At the same time, executive editor James Pope attacked the interpreters, maintaining that “by definition, interpretation is subjective and means to ‘translate, elucidate, construe … in the light of individual belief or interest….’ Interpretation is the bright dream of the saintly seers who expound and construe in the midst of the news.” To Pope and others, interpretative reporters were simply abandoning objective journalism. But the Courier-Journal has become an excellent interpretative newspaper.

Lester Markel, the able and acid retired Sunday editor of the New York Times, who was the most insistent advocate of interpretation, argued several years ago in the Saturday Review that no form of reporting could really be defined as “objective”:

The reporter, the most objective reporter, collects fifty facts. Out of the fifty he selects twelve to include in his story (there is such a thing as space limitation). Thus he discards thirty-eight. This is Judgment Number One.

Then the reporter or editor decides which of the facts shall be the first paragraph of the story, thus emphasizing one fact above the other eleven. This is Judgment Number Two.

Then the editor decides whether the story shall be placed on Page One or Page Twelve; on Page One it will command many times the attention it would on Page Twelve. This is Judgment Number Three.

This so-called factual presentation is thus subjected to three judgments, all of them most humanly and most ungodly made.

Such arguments and the findings of behavioral scientists seem to have persuaded nearly everyone that humans cannot be objective in the machine-like sense. Most of the proponents of objectivity now argue that it is a goal worth striving for even if it is not quite attainable.

The proponents of interpretation are right in arguing that mere facts must be placed in a context that gives them meaning. The reporter who explains facts and clarifies the meaning of events serves us well. Those who favor interpretation are also right in holding that a reporter can interpret the news—or analyze it—without becoming an advocate. One test is whether the writing is slanted in such a way that we can determine the reporter’s personal views. The best example of journalistic balance is provided by Richard Strout, who writes admirable interpretative news for the Christian Science Monitor that does not even hint at his own leanings, and who writes equally admirable opinion pieces—suitably labeled by the Monitor’s “Opinion and Commentary” heading—often on the same topics.

The root of the matter is made clear by James Carey of the University of Illinois, one of the most thoughtful professors of communication, who points out: “There must be greater stylistic freedom among modern journalists and a more fluid definition of news if only because the pace of social change continually presses the journalist into situations for which the conventional styles and conventional news definitions disable both perception and communication.”

Proponents of objective reporting, on the other hand, are right in arguing that few reporters are capable of interpreting complex events, either because they do not know how to explain, clarify, and analyze without advocating, or because they know too little about the subjects they are reporting to do more than present the surface of an event. Even seasoned reporters can differ sharply, as the Progressive made clear by quoting these sentences from two of the best Washington correspondents, both published January 31, 1971:

To be blunt about it, almost nobody believes President Nixon’s budget except the high officials who put it together—and it’s probable that even some of them have their doubts.—Hobart Rowen, “Credibility Is Lacking in Nixon Budget,” the Washington Post.

In general, then, insofar as decisions and judgments made at this stage are important, this budget appears to receive fairly high marks for credibility.—Edwin L. Dale, Jr., “The Budget Gap—Nixon Receives an A for Credibility,” the New York Times.

How facts can be variously interpreted was also demonstrated when the Stanford University News Bureau released information on gifts to the university for the 1970-71 fiscal year.

The university-published Campus Report headed its story: HIGHEST NUMBER OF DONORS IN STANFORD HISTORY.

The San Francisco Chronicle headline said: STANFORD AGAIN RAISES $29 MILLION IN GIFTS.

The neighboring Palto Alto Times story was headed: DONATIONS TO STANFORD LOWEST IN FOUR YEARS.

The student-published Stanford Daily announced: ALUMNI DONATIONS DECLINE: BIG DROP FROM FOUNDATIONS.

These headlines accurately reflected the stories they surmounted—which were also accurate. Stanford did have more donors than ever (as the Campus Report said), it did raise more than $29 million for the fourth consecutive year (Chronicle), donations were the lowest in the past four years (Times), and the total was lower than in 1969-70 and it included less foundation money (Daily). As proponents of objective reporting contend, a positive or negative stance can make all the difference.

But to many a new journalist, all the wrangling over objective and interpretative reporting misses the main point, which is that neither is in close touch with reality. The best objective report may cover all the surfaces of an event, the best interpretative report may explain all its meanings, but both are bloodless, a world away from the experience. Color, flavor, atmosphere, the ultimate human meaning—all these, the new journalists contend, are far beyond the reach of conventional journalism. This is one of the central reasons for the emergence of different forms and practices, but there are others. What they are can be analyzed best in the context of the forms, practices, and media that make up the new journalism:

- new nonfiction

- alternative journalism

- journalism reviews

- advocacy journalism

- counterculture journalism

- alternative broadcasting

- precision journalism

Reportage: The New Nonfiction

More than any other element of the new journalism, new nonfiction places its central focus on style. Tom Wolfe, who is one of the leading practitioners as well as the most dedicated promoter of the new journalism, has written: “The first time I realized there was something new going on in journalism was one day in 1962 when I picked up a copy of Esquire and read an article by Gay Talese entitled ‘Joe Louis—The King as a Middle-Aged Man!’ It wasn’t like a magazine article at all. It was like a short story. It began with a scene, an intimate confrontation between Louis and his third wife:

“Hi, sweetheart!” Joe Louis called to his wife, spotting her waiting for him at the Los Angeles airport.

She smiled, walked toward him, and was about to stretch up on her toes and kiss him—but suddenly stopped.

“Joe,” she snapped, “where’s your tie?”

“Aw, sweetie,” Joe Louis said, shrugging. “I stayed out all night in New York and didn’t have time.”

“All night!” she cut in. “Where you’re out here with me all you do is sleep, sleep, sleep.”

“Sweetie,” Joe Louis said with a tired grin, “I’m an ole man.”

“Yes,” she agreed, “but when you go to New York you try to be young again.”

Says Wolfe, “The story went on like that, scene after scene, building up a picture of an ex-sports hero now fifty years old.

“I couldn’t believe this stuff. How did this guy Talese ever get in on all this intimate byplay in the latter-day life of Joe Louis? He piped it. That was it. He faked the quotes, goddamn it—which was precisely the cry of self-defense that many literati would sound over the next five years as New Journalism began to shake up the literary status structure.

“Talese hadn’t piped it, of course. He was there all the time, and that was the simple secret of that.”1

Talese, a former New York Times feature writer who now devotes most of his time to writing books, cautions those who deceptively regard the new journalism as fiction: “It is, or should be, as reliable as the most r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- Preface

- 1 A Coalescing of Forces

- 2 The New Nonfiction: Brain Candy and Beyond

- 3 The Modern Muckrakers: Alternatives in Traditional Markets

- 4 Guarding the Guardians: The Journalism Reviews

- 5 The Advocates

- 6 Covering the Counterculture

- 7 Alternative Broadcasting

- 8 Precision Journalism

- 9 The Future of the New Journalism

- Afterword

- Annotated Bibliography

- Index