eBook - ePub

Academic Strategy Instruction

A Special Issue of Exceptionality

- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Academic Strategy Instruction

A Special Issue of Exceptionality

About this book

This special issue, Part II in a series devoted to the topic of strategic instruction, explores the issue of traversing the research to practice abyss through the implementation of authentic and effective business development. It reminds us that "business as usual" approaches to teacher in-service programs are unlikely to produce meaningful changes in teachers' classroom practices. In addition, this issue offers strategic instructional approaches to facilitate students' learning and focuses on structuring instruction to promote self-regulated learning. Each article raises important questions about existing practices and offers innovative alternatives to improve outcomes for students and teachers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Academic Strategy Instruction by Edwin S. Ellis, Marcia L. Rock, Edwin S. Ellis,Marcia L. Rock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralEXCEPTIONALITY, 11(1), 3–23

Articles

Implementing and Sustaining Strategies Instruction: Authentic and Effective Professional Development or “Business as Usual”?

School of Education University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Bryan Independent School District Bryan, Texas

Region IV Educational Service Center Houston, Texas

Professional development that affects teacher practices and student performance does not imply simple, short-term, 1-way solutions, or “business as usual.” Professional development that is well matched to teacher needs may be acutely important in enabling in-service teachers to teach academically diverse classes that include students with learning disabilities. Thus, the authentic professional development (APD) model was created and implemented as an effective approach for providing authentic, or teacher-friendly, professional development, particularly for the use of instructional and learning strategies from the strategies instructional model (e.g., Deshler & Schumaker, 1988). Teachers in the experimental group participated in the APD model at their schools, whereas comparison teachers participated in traditional professional development at a separate location. In this article, we describe the APD model and detail the results of a quantitative and qualitative study investigating the impact of APD on teacher use, perceived student outcomes, and teacher value.

Much is known about the effectiveness of strategies instruction for improving the outcomes of students with and without disabilities (cf. other articles in this issue). This convincing database suggests that teachers should teach students how to learn as well as what to learn and should enhance rather than water down the content for students in inclusive classes. These conclusions are illustrated most powerfully through the more than 20-year history of work conducted by researchers from and collaborators with the University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning. From their work, the strategies instructional model (SIM) was initiated and led to the validation of the learning strategies curriculum (e.g., Deshler & Schumaker, 1988) as well as the content enhancement routines (e.g., Bulgren & Lenz, 1996). The learning strategies curriculum includes a number of research-validated learning strategies for students to use independently, and the content enhancement routines are instructional strategies for teachers to use in content-area classes. Together, the strategies and routines provide a strong repertoire of tools for teaching students with and without disabilities to read, write, organize, understand, remember, and express information more effectively.

The content enhancement routines are particularly well suited for implementation by content-area teachers who teach students with learning disabilities (LD) and other disabilities in inclusive classes. As with many poor-performing students, students with LD bring a number of weaknesses to classrooms and often exhibit large deficits in academic achievement (e.g., Deshler, Schumaker, Alley, Warner, & Clark, 1982). Along with their peers, particularly at the high school level, these students are confronted with content that often contains many complex ideas, is poorly organized, and taxes students’ ability to remember numerous details (e.g., Schumaker & Deshler, 1984). Given such obstacles, the fact that a large proportion of these and other at-risk adolescents drop out of school is not surprising (U.S. Department of Education, 2000).

In response to classroom demands and student needs, content enhancement routines engage teachers in (a) making planning decisions about what critical content to emphasize in teaching, (b) transforming the content into learner-friendly formats, and (c) presenting science, social studies, or other content to academically diverse groups of students in memorable ways. In short, through application of sound instructional principles and techniques, all students’ learning is enriched without sacrifice of important content, and instruction is carried out in an engaging partnership with students.

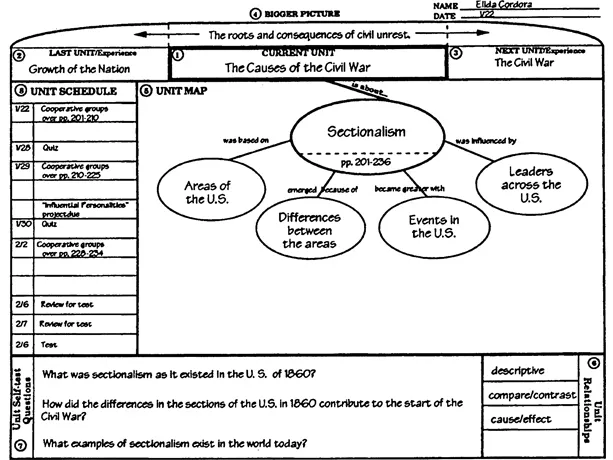

A number of content enhancement instructional strategies were developed and validated in cooperation with teachers (e.g., Bulgren, Schumaker, & Deshler, 1988, 1994) and were further translated into teacher products that are commercially available with training. One content enhancement routine is called the unit organizer routine (Boudah, Lenz, Bulgren, Schumaker, & Deshler, 2000; Lenz, Bulgren, Schumaker, Deshler, & Boudah, 1994). The unit organizer routine is used to help teachers plan for, introduce, and build a unit so that all students can (a) understand how the unit is part of larger course ideas or a sequence of units; (b) understand the gist, or central idea, of the unit through a meaningful paraphrase of the unit title; (c) see the structure or the organization of the critical unit information; (d) define the relationships associated with the critical information; (e) generate and answer questions about key unit information; (f) monitor progress and accomplishments in learning; and (g) keep the main ideas and the structure of the unit in mind as the unit content is learned. In this study, teachers and administrators chose to learn and implement the unit organizer routine. Figure 1 shows an example of the central instructional device used in this routine.

Figure 1 The unit organizer.

No matter how high the quality of validated strategies or how well designed the training materials may be, other critical factors influence the implementation and sustainability of research-based strategy instruction in classrooms. Teachers often cite barriers including the inaccessibility of teacher-friendly research reports and a lack of time for reflection on such information (Fullan, 1991; Merriam, 1986). Another important reason that validated practices are uncommon or rarely implemented is the poor match between teacher needs and in-service topics or instructional formats (e.g., Boudah & Mitchell, 1998; Guskey, 1986; Joyce & Showers, 1995). Even the most well-intentioned teacher in-service plans that district administrators make at the beginning of the school year often result in few classroom changes when such plans are operationalized without significant teacher engagement throughout a long-term change process, involvement of key change agents, and essential time and money. As a result, many teachers typically acquire strategies and materials for classroom use by simply walking down the school hall and asking for ideas or activity suggestions from a colleague (Kaestle, 1993).

Furthermore, researchers (Boudah, Logan, & Greenwood, 2001) working on research- to-practice projects, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs, concluded that development, implementation, and sustainability of research-based practices in special education require the following: (a) an up-front commitment by researchers and teachers, as well as an ongoing, honest relationship; (b) intensive work by researchers and teachers; (c) extensive, sustained effort; (d) building-level (although not necessarily district-level) administrative support; (e) the involvement of key individuals; and (f) financial resources and teacher recognition. These researchers’ “lessons learned” were similar to those that Schumm and Vaughn (1995) suggested.

Therefore, a critical need exists for increased and improved professional development that has an impact on teacher implementation and sustainability of validated strategies, particularly for addressing the needs of academically diverse classes that include students considered at risk for failure and mainstreamed students with LD. The purpose of this project was threefold: to develop and implement a successful alternative in-service professional development model for teachers, to facilitate the use of research-based instructional strategies in classroom practice by using the model, and to measure the impact on teacher performance and satisfaction as well as student academic outcomes.

Authentic Professional Development Model

The authentic professional development (APD) model was initially developed to provide an effective professional development approach for teachers, particularly for implementing instructional and learning strategies from the SIM. The APD model was based on four principles that were translated into a set of specific staff development activities used to address instructional challenges in academically diverse classrooms. According to the APD model, authentic and effective professional development is characterized by (a) quality instruction for adult learners, (b) teacher empowerment, (c) well-matched needs and activities, and (d) sustainable improvements in instruction.

First, the APD model is characterized by the element of quality instruction for adult learners. Adult learners require clear objectives, explicit instruction of theory and skill procedures, observation of demonstrations of practice, individual practice, and feedback so that they can learn effectively and incorporate new skills (Loucks-Horsley et al., 1987; National Partnership for Excellence and Accountability in Teaching [NPEAT], 2000).

Second, the APD model includes teachers as active participants in setting the agenda for the change process, which thereby empowers them to change instructional practices (Hunsaker & Johnston, 1992; Snyder, Bolin, & Zumwalt, 1992). Hence, according to Meyerson (1993), “an educational innovation will be successful when it is viewed by teachers as introspective evolution rather than dictated revolution” (p. 165).

Third, staff development processes and activities must match the needs of stakeholders. All training is aimed at current, relevant problems and issues that teachers are facing within the classes that they teach (Bradley & West, 1994). By addressing real instructional problems in actual classroom settings, the staff development process itself, as well as the instructional strategies implemented, becomes educationally realistic, valid, and useful (Fullan, 1991).

Fourth, by incorporating specific and individualized teacher follow-up, the instructional changes are likely to be more sustainable. Collegial support and follow-up are conducted by knowledgeable colleagues, who provide coaching to teachers as they implement and refine instructional interventions (e.g., Fullan & Hargreaves, 1996; Joyce & Showers, 1995).

Setting and Participants

This study occurred in a school district in the U.S. South-Southwest. The 350-square-mile district serves more than 28,000 students and is growing at a rate of 5% annually. The district employs more than 2,000 professional staff members who serve a diverse student population residing in rural areas as well as in planned communities. In recent years, the district has increased its emphasis on including students with disabilities in general education classes for instructional services. Concurrently, the State Education Agency also reduced the number of staff development days to 1.5 per year. Teachers must attain additional staff development by using personal time.

This study comprised two parts: an experimental (quantitative) part and a model evaluation (qualitative) part. The experimental part of the study involved 57 teachers who participated in one of two forms of staff development training on the same instructional str...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Preface

- Articles