Dating Buildings and Landscapes with Tree-Ring Analysis

An Introduction with Case Studies

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Dating Buildings and Landscapes with Tree-Ring Analysis

An Introduction with Case Studies

About this book

This book presents guidance, theory, methodologies, and case studies for analyzing tree rings to accurately date and interpret historic buildings and landscapes.

Written by two long-time practitioners in the field of dendrochronology, the research is grounded in the fieldwork data of approximately 200 structures and landscapes. By scientifically analyzing the tree rings of historic timbers, preservationists can obtain valuable information about construction dates, interpret the evolution of landscapes and buildings over time, identify species and provenance, and gain insight into the species matrix of local forests. Authors Darrin L. Rubino and Christopher Baas demonstrate, through full-color illustrated case studies and methodologies, how this information can be used to interpret the history of buildings and landscapes and assist preservation decision-making.

Over 1,000 samples obtained from more than 40 buildings, including high style houses, vernacular log houses, and timber frame barns, are reported. This book will be particularly relevant for students, instructors, and professional readers interested in historic preservation, cultural landscapes, museum studies, archaeology, and dendrochronology globally.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Can you date my building

1.1 Introduction

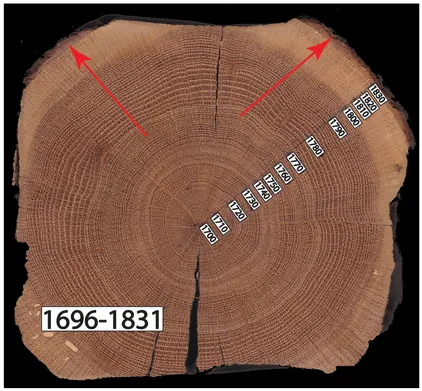

Cross section of a white oak beam from a southern Indiana log house. The tree rings in this timber were dated from 1696 to 1831; tree rings can be identified by the alternating light and dark woody tissue. Note that not all of the rings have the same width. The variation in ring size is related to the growth conditions experienced by a tree in a given year. Depending on the amount of resources available for growth, such as light or water, trees will produce larger or smaller rings. Tree rings, therefore, record what a tree experienced while it was growing. Since the last ring in this timber is next to the bark (arrow), we can determine that the tree was felled in 1831 and subsequently was used for construction.

Source: Authors.

1.2 An overview: can you date my building?

1.2.1 Buildings and landscapes

1.2.2 Understanding how trees grow

1.2.3 Basics of tree-ring science

1.2.4 Obtaining a construction date

- Presence of bark or wane. In order to give an accurate construction date to a building, it is necessary to determine when the trees used to erect it died. Determining a death or felling date of a tree requires assigning a calendar date to the last year it formed a ring. This is the ring adjacent to the bark (Figure 1.1) or a ring associated with wane (the outermost ring if the bark has been removed or sloughed off. Wane is identified by noting a smooth, rounded outer surface on a log that is free of tool marks (Figure 1.2). When multiple timbers from a structure have the same or similar death dates we can determine the construction date of a building. If none of the accessible timbers of a building have bark or wane, calendar dates can still be assigned to the tree rings in the timbers, but an exact construction date cannot be determined (Figure 1.3).

Floor joists from a southeastern Indiana barn. These ash floor joists (arrows) exhibit wane, a smooth outer surface with no bark present. If the outermost ring in these joists can be dated, the felling or death date of the tree can be determined. When several timbers from throughout a building have the same or comparable death date, one can determine a construction date for a building.

Source: Authors.

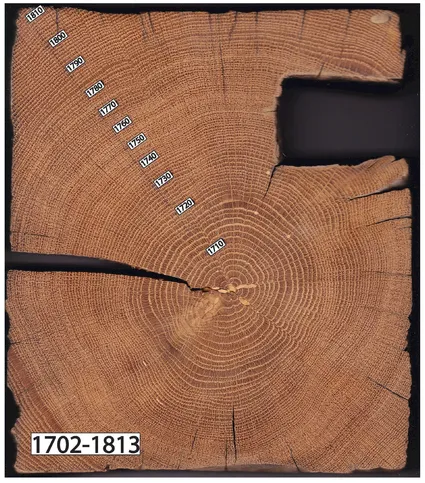

Cross section of a white oak post from a log house. This timber was made by removing woody tissue from a fallen tree so that a square shape was achieved. This timber has no bark or wane, and it is not possible to determine how many rings were removed when it was squared. Therefore, the exact year of felling cannot be determined. The outermost ring in this sample is 1813 so we know this timber was put into service at some undeterminable year after 1813. The structure from which it was taken was built sometime after this date.

Source: Authors.

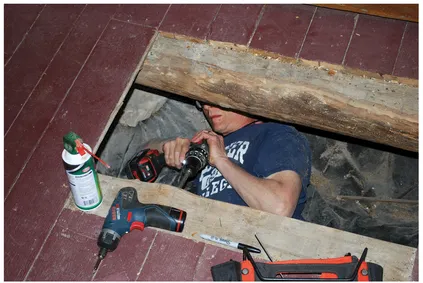

- Timber accessibility. Dating historically erected buildings requires extraction of wood samples from timbers from throughout a structure. In some structures, such as barns, sampling is fairly straightforward, because the timbers are readily accessible. Buildings such as houses and churches pose sampling problems because construction timbers are covered with plaster or other wall finishes, and access to structural timbers is not possible without causing major damage. In these buildings, we rely on sampling in crawlspaces, cellars, and attics (Figure 1.4). During renovations we have had great success in accessing timbers for dating (Figure 1.4; see also the Huxford House in Chapter 10, the Wyneken House in Chapter 8, and Musée de Venoge in Chapter 9).

To provide accurate construction dates for a building, samples from timbers must be obtained for analysis. Top: Sampling in buildings with finished walls is often done in cellars or crawlspaces, since the floor joists of the ground floor are usually accessible. Bottom: During renovation, samples are easily extracted, since wall coverings have been removed. During the renovation of Eleutherian College (Chapter 9), all of the baseboards (white boards in the foreground) were removed from the plastered walls. We were able to access and sample a large number of timbers without causing damage to finished walls. The vertical wooden timbers (center) are wall studs.

Source: Authors.

- Multiple samples are needed. Determination of a building’s construction date requires more than dating a single timber. Historical buildings have stood for extended periods of time (approximately two-century maximum where we work, but much, much longer in other parts of the world such as Europe and Asia). During this time, the fabric of buildings is routinely altered, and renovations and additions are made (see the Fauntleroy House, Chapter 11). New timbers are added to repair damaged timbers due to rot and insect damage (see Delphi’s Canal Park, Chapter 8). Additionally, buildings are often erected fully or in part with recycled timbers (see the Thiebaud and Posey...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgments

- Conventions

- 1 Can you date my building: an introduction to tree-ring analysis for dating buildings and landscapes

- 2 Understanding cultural landscapes and historic buildings: frameworks for interpreting and communicating tree-ring analysis

- 3 Botany for the dendrochronologist

- 4 Tree-ring basics for the historian, archaeologist, and preservationist

- 5 Tree-ring analysis methods for the field, woodshop, and lab

- 6 Archival and scholarly sources for interpreting tree-ring analysis

- 7 Reporting the results of tree-ring analysis

- 8 Enhancing interpretation: case studies for open air and house museums

- 9 Case studies: dating and interpreting diverse cultural landscapes

- 10 Chronicling landscape evolution using tree-ring analysis

- 11 New Harmony, Indiana: tree-ring analysis of a communal and utopian landscape

- 12 Innovation to obsolescence: tree-ring analysis of a regional barn type

- 13 Unique applications of tree-ring data

- 14 Active inquiry: dating a 19th-century log house using historical documents and tree-ring science

- Index