- 89 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Applying Psychology in the Classroom

About this book

First Published in 1999. Each publication in this series of books is concerned with approaches to intervention with children with specific needs in mainstream schools. This book is written primarily for newly qualified primary teachers and any teachers interested in the application of psychologically based approaches in the classroom. Its orientation is eclectic, drawing on a variety of psychological theories we have found useful in our work as educational psychologists in schools.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Applying Psychology in the Classroom by Jane Leadbetter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The inclusive classroom: taking account of the individual

Introduction

Within this book each chapter attempts to address current issues which are important for practising teachers and to consider how the use of psychological knowledge can improve their practice in the classroom. In this chapter, we consider current developments in the education of children with special educational needs and in particular the move towards more inclusive education. The approach taken is itself inclusive as it considers all children as individuals, rather than focusing upon children with special needs in particular, and looks at the skills which are necessary for teachers to become more effective with every individual in their class.

Effective teaching implies a reflective approach where practitioners scrutinise all aspects of their practice and aim to continuously improve on their previous best. In this area, more than any other, the beliefs, attitudes and values of practitioners play an important part in the success of individual children and so it is important that we reflect on our own attitudes in relation to children with special needs and appropriate education for them.

Inclusive education is a term which is becoming common parlance in educational circles and yet many teachers are confused about its meaning, its relevance to them and its relationship to the integration of pupils with special educational needs. None of this is surprising, as it is a movement which has gathered pace during the 1990s and which has its roots not in theory or research findings but in beliefs around human rights and equality of access and opportunity. Inclusion is a term that can refer to any group of pupils who have been segregated or discriminated against either in terms of access to educational opportunities or equity of provision or support once in a placement. It does not just cover children with disabilities but can also refer to ethnic or religious groups who may suffer discrimination. Exclusion of children who pose severe behaviour difficulties in schools represent a growing group and attention is beginning to focus upon such children whose educational prospects are severely impaired by exclusion. In the wider context, ‘social exclusion’, which indicates a large group of children and adults who are excluded from the normal ‘walks of life’ or ‘courses of action’ is a term which is now in common use in political, social and educational circles.

In 1994, UNESCO issued the Salamanca World Statement on Special Needs Education that called for the inclusion of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools and this has been adopted as a basis for recent educational policy documents in many countries, including the United Kingdom. Policy documents such as Excellence in Schools state: Where children do have special educational needs there are strong educational, social and moral grounds for their education in mainstream schools (DfEE 1997, 34).

It is clear, therefore that this movement has strong political and international backing as well as a forceful body of advocates from the disabled community and their supporters. Mainstream classroom teachers are a key group who need to be involved in the planning and delivery of inclusive education and therefore it is important that this wider context is understood.

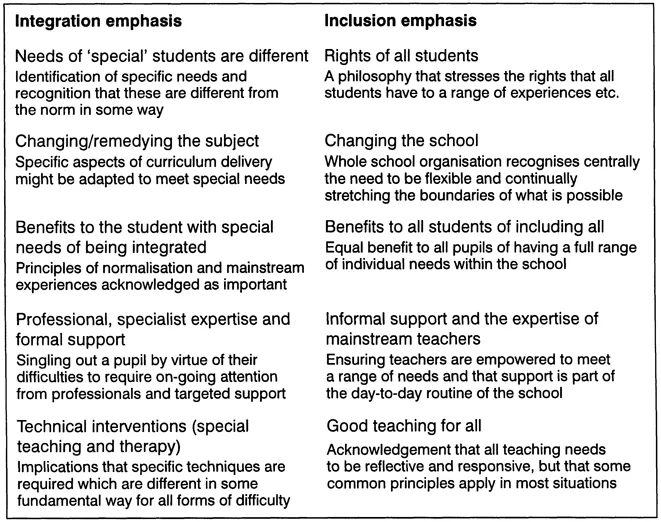

Many teachers are puzzled by the change in terminology from integration to inclusion and there are no universally agreed definitions of either term that might clarify matters. However, Walker 1995 attempts to contrast the two approaches and Figure 1.1 shows an adaptation of Walker’s model showing some of the characteristics of each approach.

Figure 1.1 Integration or inclusion

Although this figure presents some stark contrasts, it can be used as a yardstick for schools to gauge where they are in terms of their attitudes and moves towards inclusion. Alternatively, as a tool for reflection, it can help individuals to clarify their own attitudes and beliefs concerning the education of children with special needs.

Work in one local authority has sought to help schools to evaluate where they currently are in terms of inclusion and to give guidance as to how they might make more progress. It has used the notion of self-evaluation and continuous improvement and is part of a wider school improvement programme. An audit approach is used initially, completed by staff within the school. The materials, from Bonathan, Edwards and Leadbetter 1998, are included as Appendix 1.1. This is a flexible resource but is best used by staff working within the school, with an interest in special educational needs.

Psychological basis for inclusion

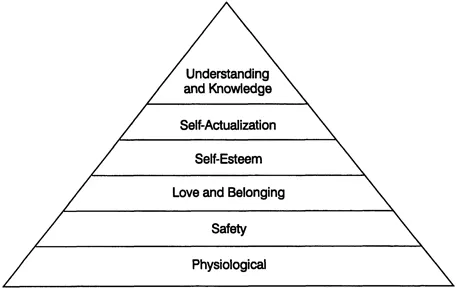

Psychology has been the driving force in contributing to our understanding of human motivation and this is addressed in more detail in other chapters in this book. However, it is important to understand the fundamental importance of basic needs when we consider the appropriateness of different forms of education. As long ago as 1943, Maslow described a hierarchy of basic human needs which he felt we all strive to meet, at ascending levels from the most basic to more sophisticated needs and it is this hierarchy, Maslow suggests, that governs our drives and motivation. He prioritised human needs into five levels, which are shown in Figure 1.2.

From the figure it can be seen that ‘belonging’ is a very basic human need occurring once physiological needs and safety needs are fulfilled. This is something we can all

Figure 1.2 A hierarchy of needs

Based on A. H. Maslow, ‘A theory of human motivation’, Psychol. Rev., 50, 370-396 (1943)

Based on A. H. Maslow, ‘A theory of human motivation’, Psychol. Rev., 50, 370-396 (1943)

recognise from experiences in childhood and often in later life. The need to feel part of a group, not ‘different’ in some way is important for all of us. Therefore, segregation or separation from peers can have a profound effect on children. Continuing this argument, for all children to belong to their neighbourhood communities and schools they need to be included from the start. For most pre-school children this can occur but often decisions are made at school age which set the path for a child’s educational future.

Inclusion, as Micheline Mason, a disability rights spokesperson, points out, is not something that can be done to us. It is something we have to participate in for it to be real (Pugh and Macrae 1995). This word participation is important as it implies activity, rather than passivity and meaningful experiences rather than token placements, either at a locational, social or functional level.

Although it is acknowledged that for inclusion to work well there needs to be support at all levels from the Local Education Authority through to whole-school policy level and including the parent and pupil, in many cases, it is the class teacher who is the prime mover in designing the learning environment and learning programmes for a range of children with a huge variety of needs within the classroom. This chapter will therefore move on to address some of these difficulties and consider approaches that have been found to be successful in promoting inclusion.

Taking account of the individual

The National Curriculum provides a framework for teachers to plan and deliver the curriculum across each school year but it does far more than this. It provides yardsticks against which children’s attainments can be measured and alongside this, means by which their rates of progress can be monitored. We are therefore all working within an educational environment where information is available and indeed required of us; this can be seen as a daunting administrative task or as an essential tool for planning our teaching and delivery – more likely for most teachers it is a bit of both!

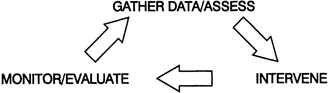

Using a simple cyclical model, various phases can be implemented in order to provide effective teaching for the pupil. A model as shown in Figure 1.3 includes all essential elements.

Figure 1.3 Model for using information

Alongside National Curriculum information, which is available for all children, there will be children with special educational needs who are identified on the school’s special needs register at one of the Code of Practice DfEE 1994 stages. Therefore, this means that there has been some measure of concern expressed, ranging from an early class teacher observation that the child seems to be experiencing a measure of difficulty in a particular subject area, to a child with a statement of their special educational needs who has a major disability and has individual support allocated specifically for them. For each child with special needs, more specific assessment and planning will need to be undertaken.

Chapter 2 looks at optimal learning environments for children, taking a broad perspective, and examines ways of improving the classroom environment for all children. Likewise this chapter, focusing as it does upon the individual, also has wider implications for all pupils. Good teaching practice, however and wherever it occurs is equally applicable for all children, whether or not they have special educational needs. A skilled teacher will be able to run a successful classroom using generally applicable routines, methods and techniques but will also be able to take account of individual needs within this setting. How then, can this be done?

Information gathering

It should be an increasingly rare event for a pupil to arrive in a class with no information about them available to the teacher. National Curriculum and SEN records should be transferred with the pupil in order that programmes can recommence at the point where they were left. However, inevitably, there may be some chasing of information, particularly from services or agencies who have been involved with children and families and who may not know that the children have moved. Therefore, either via the Special Needs Coordinator (SENCO) or the head teacher, it is vital that the class teacher, obtains all available information.

This is not the only source of information that a teacher can access. Where appropriate and possible, taking some time to talk to the pupil in depth can reveal not only their interests and some background information, but information about their linguistic skills, their previous schooling, programmes and levels of support. We will turn to involving pupils in their own learning later in Chapter 5, but using them as an information source is often neglected.

Alongside this, both formal and informal contact with families is vital in terms of obtaining information about such matters as:

- what has worked well in the past and what has not met with success both at home and at school;

- the family’s hopes for the placement;

- the level of support which is likely to be available within the home.

Remember that this can take place at the information gathering stage. By treating parental information in a serious and professional manner you are more likely to enlist the parents’ support at the intervention stage.

Assimilating and analysing the information

Often when we are confronted by a new problem situation, even though there are resources and information available (a new pupil might arrive with a bulging file and support on hand) it sometimes seems impossible to know where to begin to work with the pupil. Some time spent analysing the wealth of information and different viewpoints, using some of the suggestions outlined above, is time well spent. If the class teacher is able to do this in a collaborative manner with a supportive and informed colleague e.g. the SENCO, so much the better.

By using a simple listing technique to identify all the apparent difficulties and then using a hypothesis-testing approach, considering all the possible reasons or causes for a particular concern, a way forward can usually be found. Miller (1991, p. 197) gives an example of a boy of eight whose behaviour in class is described as disruptive and restless. He offers 13 different hypotheses or possibilities to account for the boy’s behaviour; some at a physiological or neurological level, others from a developmental or cognitive point of view and yet others from a social angle. Any of these possible explanations could have been used as the basis of a plan of action.

When there are a number of competing concerns, it can be difficult to decide which one to work on. A problem solving approach, see Leadbetter and Leadbetter (1993, p. 74), offers a way forward and within this, asking a series of questions in order to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The inclusive classroom: taking account of the individual

- Chapter 2 Understanding the learning environment

- Chapter 3 Managing the social dynamics of the classroom

- Chapter 4 De-stressing children in the classroom

- Chapter 5 Exploring pupil motivation and promoting effective learning in the classroom

- Chapter 6 Conclusions: using psychology as a basis for action

- Appendices

- References