![]()

CHAPTER 1

Sterilization of Apparatus and Culture Media

I. INTRODUCTION

Pure culture techniques are used for isolation, identification and multiplication of plant pathogens, for increasing inoculum, and for studying their biology and physiology. All require sterile conditions. Sterilization of apparatus and working areas involves the inactivation or physical elimination of all living cells and infective agents from the environment. It does not include the destruction or elimination of constitutive enzymes, metabolic by-products, or removal of dead cells.

Sterilization is achieved by exposing materials to lethal agents which may be chemical, physical, or ionic in nature or, in the case of liquids, physical elimination of cells or infective agents from the medium. Selection of a method depends on the desired efficiency, its applicability, toxicity, ease of use, availability and cost, and effect on the properties of the object to be sterilized. Several publications review the theoretical aspects of sterilization methods.1, 2, 3, 4 The methods commonly used for sterilization are gas, heat, and in the case of liquids, ultrafiltration.

II. HEAT STERILIZATION

Heat is the most reliable method for sterilization when the material to be sterilized is not modified by high temperature. High temperature can be attained by using either dry or moist heat. The mechanisms of cell destruction by heat were reviewed.5 The chief mechanism of death is oxidation or coagulation of proteins.6

A. DRY HEAT

Dry heat is used for the sterilization of glassware, metal instruments, certain plastics, and heat-stable compounds. The action of dry heat is an oxidation process resulting from heat conduction from the contaminated object and not from the hot air surrounding it. Thus, the entire object must be heated to a temperature for a sufficient length of time to destroy contaminants. Dry heat requires higher temperatures for longer duration than moist heat for sterilization because heat conduction by the former is slower than the latter. Many bacteria in a desiccated vegetative state or as spores can survive dry heat at high temperatures.

Hot air ovens equipped with a thermostat and heated either by electricity or burning gas are used for dry heat sterilization. Heating of objects is by radiation from the oven walls, and unless equipped with a fan to circulate the air within the chamber, heating of objects is uneven, especially if the heat source is in the oven base. To determine whether or not a uniform temperature occurs throughout the load, thermometers should be placed at different sites within the chamber.

The time required for sterilization is inversely proportional to temperature. Commonly used time per temperature regimes are 1 hr at 180°C, 2 hr at 170°C, 4 hr at 140°C, or 12 to 16 hr at 120°C. Exposure time is counted from when objects to be sterilized have reached the desired temperature inside the oven. The air in the oven heats faster than the objects to be sterilized; therefore, the duration of the heat treatment should be increased by 1.0 to 1.5 hr over suggested time allowing the objects to reach the sterilizing temperature.

Glassware should be completely dry before placing in a hot air oven since wet glassware may break. Objects, such as glass culture plates, should be placed in sealable metal or other heat-resistant containers to prevent recontamination during cooling, transport, or storage. The objects can be wrapped in heavy paper if metallic containers are not available. However, paper may leave organic residue and become brittle and charred. Dry heat sterilization using paper should be done at low temperatures and for longer times than if metal containers are used. Calibrated glassware should not be sterilized with dry heat since the expansion and contraction can cause changes in the graduations. Objects with tight-fitting joints or plugs should be separated during hot air sterilization; otherwise, they may break.

Sterilization chambers whether using dry or wet heat, should be loaded in such a way as to provide ample space between items allowing for air circulation and to avoid breakage. Containers plugged with cotton, plastic, or rubber stoppers should be sterilized at lower temperatures for longer times. Slip-on metal caps can be substituted for cotton for culture tubes. Rubber-stoppered or screw-cap bottles, flasks, or culture tubes should be sterilized with moist heat.

After sterilization, the oven and its contents should be allowed to reach ambient temperature before opening to prevent breakage and recontamination by cool air rushing into the chamber. Sterilized material may remain in the oven until used or stored in a dry area free of air currents, but should be used within a short time and not stored for long periods.

B. MOIST HEAT

Moist heat is usually provided by saturated steam under pressure in an autoclave or pressure cooker, and is the most reliable method of sterilization for most materials. It is not suitable for materials damaged by moisture or high temperature, or culture media containing compounds hydrolyzed or reactive with other ingredients at high temperature. Moist heat has advantages over dry heat in that conduction is rapid and the temperature required for sterilization is lower and the duration of exposure is shorter. Materials to be sterilized should be in contact with the saturated steam for the recommended time and temperature.

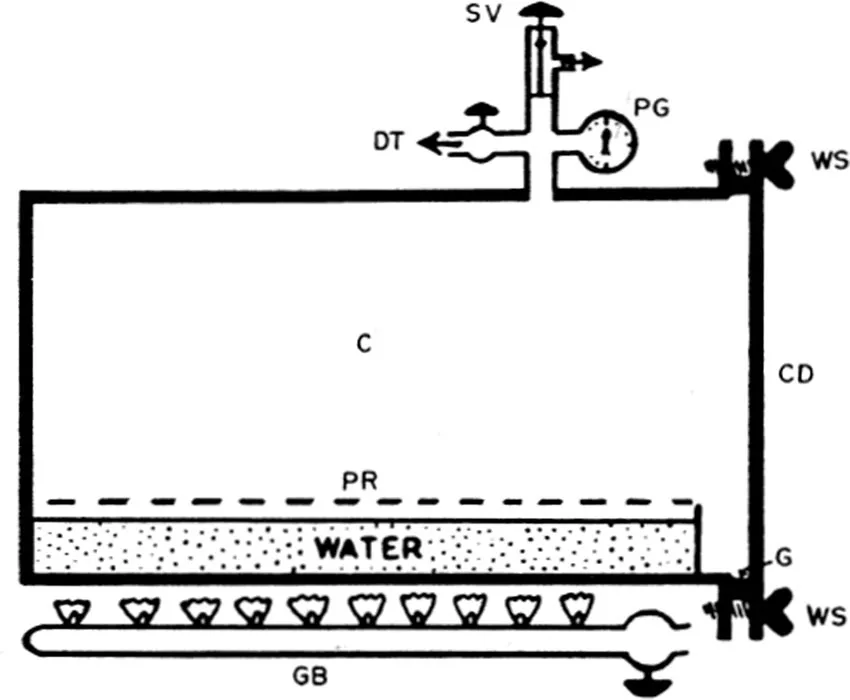

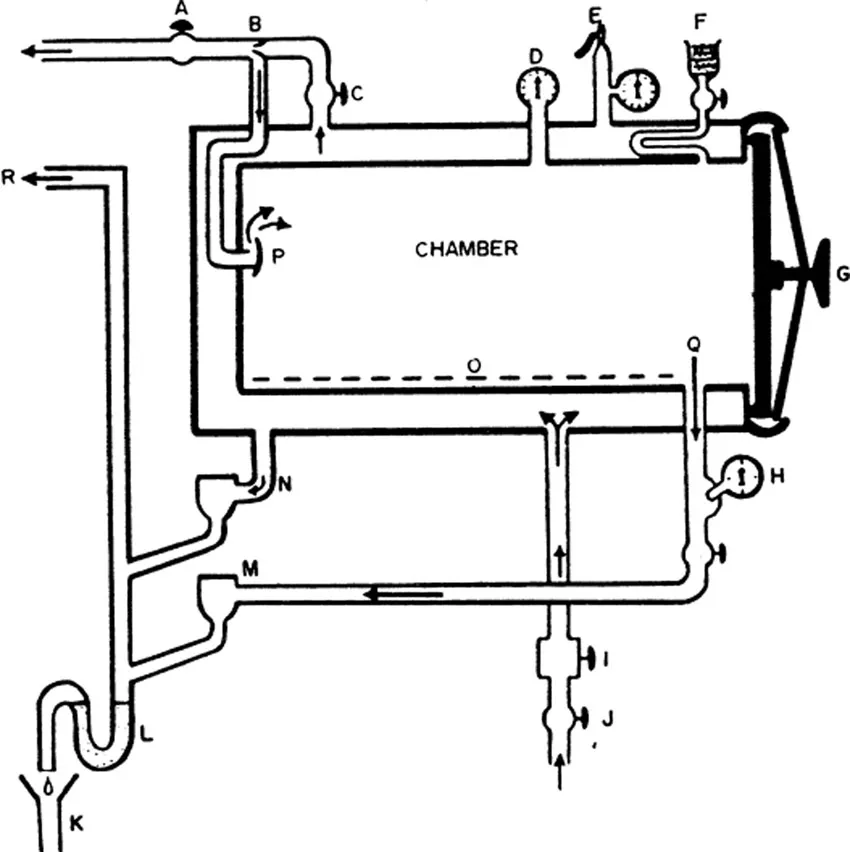

The process is usually carried out in an autoclave7 or a kitchen-type pressure cooker equipped with pressure gauges, thermometer, automatic pressure control valves, and exhaust valves. Autoclaves may be nonjacketed (Figure 1-1) or jacketed (Figure 1-2). In jacketed types, the duration for heating is less than in the nonjacketed types, moisture does not condense on objects, and the steam is “dry”, i.e., it does not contain particulate water.

Steam is supplied either from a central source or is generated within the autoclave (or pressure cooker) by electric or gas heating. Pressure cookers and autoclaves are available in a variety of sizes and models (follow operationing instructions provided by the manufacturer).

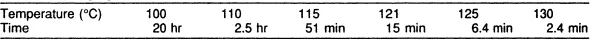

The temperature and length of time for sterilization with steam are different from that of dry heat. Thiel et al.8 calculated the time required for sterilization at temperatures ranging from 100 to 130°C (Table 1). For most purposes 15 min at 121°C or 30 min at 115°C are suggested. If the level of contamination is low, then 10 min at 121°C or 20 min at 115°C can be used. These temperatures are attained at 1.1 kg/cm2 or 0.7 kg/cm2, respectively.

Figure 1-1. Schematic diagram of a simple horizontal nonjacketed autoclave: C, chamber; PR, perforated tray; GB, gas burner; G, gasket; WS, wing screw, CD, chamber door; PG, pressure gauge; SV, adjustable safety valve; DT, chamber discharge tap. (From Cruickshank, R., Handbook of Bacteriology: A Guide to the Laboratory Diagnosis and Control of Infection, E. & S. Livingston, Edinburgh, 1960. With permission.)

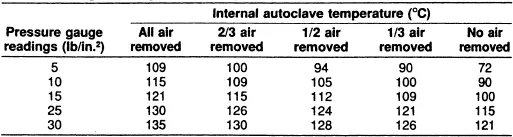

All of the air must be removed from within the chamber before closing the exhaust valve. The effect of air removal on temperature is summarized (Table 2). Sterilization begins after the load has reached the desired temperature. The preheating times required for various liquid volumes are 2 min for loosely packed culture tubes containing 10 ml; 5 min if tightly packed; 5 min for flasks or bottles containing 100 ml plugged with cotton or loosely screwed caps loosely packed; 10 to 15 min for 500 ml, 15 to 20 min for 11; and 20 to 25 min for 21. If flasks or bottles are stacked or layered, the preheating time should be increased 5 to 10 min. It is not desirable to autoclave large and small volumes at the same time because of the different preheating and autoclaving times. Empty or dry containers should be loosely stoppered and placed horizontally to allow for the movement of air and steam; sterilization requires 35 min at 121°C.2,3

Culture media are altered by heat treatment. The effect may be harmful or beneficial, but no medium should be exposed to more heat than necessary. The medium pH usually is changed by 0.2 to 0.4 units; carbohydrates are partially hydrolyzed and the nature of proteins may be changed. Glucose and amino acids may react to form compounds inhibitory to microorganisms.9, 10, 11 Excessive autoclaving partially hydrolyzes agar-agar, which can inhibit microbial growth.12

Acidified agar does not gel properly when autoclaved, thus, acidification is done after autoclaving. Additives, such as antibiotics, hormones, vitamins, and other compounds may be destroyed by heating and therefore should be sterilized by filtration or other means and added after autoclaving the medium. (Remember that when liquids are mixed a dilution factor must be considered.)

Figure 1-2. Schematic diagram of a steam jacketed autoclave with automatic gravity discharge of air and condensate, and system for drying by vacuum and intake of filtered air: A, chamber discharge and vacuum valve; B, venturi tube; C, steam to chamber valve; D, chamber pressure gauge; E, jacket safety valve and pressure gauge; F, air intake and filter; G, chamber door, H, thermometer; I, pressure regulator; J, steam supply valve; K, drain; L, vapor trap, M, chamber steam trap; N, jacket steam trap; O, perforated tray; P, baffle; Q, discharge channel; R, discharge to atmosphere. (From Cruickshank, R., Handbook of Bacteriology: A Guide to the Laboratory Diagnosis and Control of Infection, E. & S. Livingstone, Edinburgh, 1960. With permission.)

Table 1. Theoretically Calculated Time Required for Sterilization at Steam Temperatures Ranging from 100 to 130°C8

Table 2. Effect of Amount of Air Removed from the Autoclave at Various Pressure Gauge Readings on the Temperature Attained in the Autoclave6

Certain precautions must be taken when using an autoclave or pressure cooker. All vents, exhaust values, and safety valves as well as the chamber should be kept clean. Use nonabsorbent cotton for plugs, which should be loose enough to allow for access of steam and air exhaust during decompression. If the volume of liquids is critical, screw-cap containers may be used or a compensation of 3 to 5% water loss should be made. If screw-cap containers are used, treatment time may have to be increased 5 min over cotton-plugged containers. Always check the effect of heat on an object or material to be autoclaved before beginning the process. Containers should be no more than one- half to two-thirds full. All air should be replaced before closing the exhaust valve. Exhaust of steam after autoclaving should be slow to prevent blowing of stoppers and boiling of liquids.

C. FLAME STERILIZATION

Flame sterilization is used for metal objects, such as transfer needles and tips of forceps, and glass objects, such as the lips of flasks and culture tubes, microscope slides and cover slips, and the surface of certain plastics. The object to be sterilized is held at a 45° angle in the upper portion of a flame from a bunsen burner or alcohol lamp. Tempered metal can be heated to “red hot” and remains sterile as long...