- 382 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

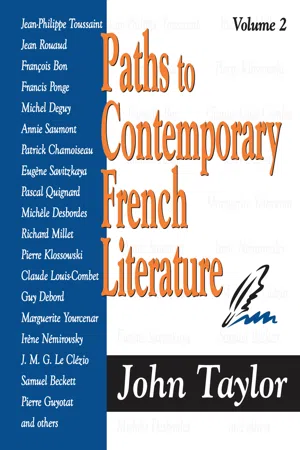

The first volume of Paths to Contemporary French Literature offered a critical panorama of over fifty French writers and poets. With this second volume, John Taylor an American writer and critic who has lived in France for the past thirty years continues this ambitious and critically acclaimed project.Praised for his independence, curiosity, intimate knowledge of European literature, and his sharp reader's eye, John Taylor is a writer-critic who is naturally skeptical of literary fashions, overnight reputations, and readymade academic categories. Charting the paths that have lead to the most serious and stimulating contemporary French writing, he casts light on several neglected postwar French authors, all the while highlighting genuine mentors and invigorating newcomers. Some names (Patrick Chamoiseau, Pascal Quignard, Jean-Philippe Toussaint, Jean Rouaud, Francis Ponge, Aime Cesaire, Marguerite Yourcenar, J. M. G. Le Clezio) may be familiar to the discriminating and inquisitive American reader, but their work is incisively re-evaluated here. The book also includes a moving remembrance of Nathalie Sarraute, and an evocation of the author's meetings with Julien Gracq Other writers in this second volume are equally deserving authors whose work is highly respected by their peers in France yet little known in English-speaking countries. Taylor's pioneering elucidations in this respect are particularly valuable.This second volume also examines a number of non-French, originally non-French-speaking writers (such as Gherasim Luca, Petr Kral, Armen Lubin, Venus Ghoura-Khata, Piotr Rawicz, as well as Samuel Beckett) who chose French as their literary idiom. Taylor is in a perfect position to understand their motivations, struggles, and goals. In a day and age when so little is known in English-speaking countries about foreign literature, and when so little is translated, the two volumes of Paths to Contemporary French Literature are absorb

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paths to Contemporary French Literature by John Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

The Voice behind the Prose

Remembering Nathalie Sarraute

When I returned from the Saturday fruit market a message was blinking on my answering machine. I pushed the stiff button and almost as soon heard an elderly female voice slowly but firmly pronounce the words: “C’est Nathalie Sarraute.” She explained that she had read my review of the recent Gallimard “Pléiade” edition of her Oeuvres complètes (an essay published in the Times Literary Supplement on April 25, 1997), and that she was wondering whether I ever came to Paris. (I live in central-western France, about two hundred miles from the capital—an hour-and-a-half train ride.) “I would be happy to meet you,” she added. “Perhaps you could come for a visit some afternoon.” Before leaving her telephone number and hanging up, she remarked mischievously: “Of course, I don’t agree with everything you wrote. We can talk about that!”

After hesitating several minutes, all the while examining my date book and recalling the concluding arguments of my article (in which I had suggested that personal sources might underlie her notoriously indeterminate “characters,” often designated by mere “he’s” and “she’s,” and especially that her fiction might represent a paradoxical quest for selfhood), I called back and was greeted by a charming almost-ninety-seven-year-old. (Sarraute was born, as Natalia Tcherniak, on July 18, 1900, in Ivanovo, Russia.) She was always delighted, she confessed, to be read by the British. When I pointed out that I was actually an American, in fact originally from l’Amérique profonde—Iowa—she laughed and claimed not to be disappointed. She had traveled often in the States, having been invited by various universities, and had met with students at New York University as late as 1995. “My lifelong goal has been to speak English like the Queen,” she chuckled, perhaps ironically, and she recalled how she had studied chemistry and history at Oxford in 1920–21, just after obtaining from the Sorbonne the equivalent of a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature. “Just now, in the new book I am working on,” she continued, “there is a French expression that, I am sure, will give my English translator fits. I’ll show it to you when you come.”

* * *

Ten days later, at four in the afternoon, I rang the doorbell at her first-floor apartment in a large building located at No. 12, avenue Pierre 1er de Serbie, a busy avenue taking off from the place d’Iéna—one of the wealthiest, most stolid residential districts of the city. The Guimet Museum, devoted to Oriental art, stands on the place d’Iéna; and not far away lies the Goethe Institut, the German cultural center. In Paris these days, one usually hears several sturdy locks turning before a door is opened; and often there is a chain blocking the door until the inhabitant can peek out and see who is knocking. No such protective devices for Nathalie Sarraute. The wooden door swung open forth-rightly, and there she was, the just-slightly-bent-over author of The Age of Suspicion, standing in the hallway, smiling, and holding out a friendly hand for me to shake.

She ushered me into a book-lined parlor, had me sit down in an armchair facing a backless single-bed-like banquette covered with cushions, and asked me what I would like to drink. It was a hot day. I had taken a long métro ride from the Montparnasse station, changing lines once, which obliged me to make my way through the crowds filling the stuffy corridors of the Trocadéro station. “Anything will be fine,” I replied, “a glass of water would be perfect.” “Oh no,” she grinned, looking up at me through the thick lenses of her glasses. “You need one of my Bloody Marys. I hope you won’t mind if I have the glass of water—because of my age.”

As I was opening, at her request, a new bottle of some special Russian vodka that she had managed to procure, she invoked our common “immigrant” status. This surprised me, all the more so since she insisted on her “un-Frenchness.” I had been living in France since 1977, a long Gallicizing stretch of time, but Sarraute had first come to France at the age of two, some ninety-five years beforehand. She was thereafter raised bilingually, in French and Russian, while living principally, but not exclusively, in Paris. A few months now and then were spent in Saint Petersburg or Ivanovo, as well as in Switzerland, where she was tutored in German, a language that she perfected while studying history and sociology at the University of Berlin in 1921–1922. It struck me firmly that afternoon, as it still strikes me today (some four months since her death in October, 1999), that Sarraute’s bilingualism and biculturalism represent something fundamental that we should keep in mind when we are reading her fiction, so dependant—especially in her final long period of creativity, which began in the mid-1960s and during which she also wrote six plays—on minute analyses of everyday conversation. Her Russian origins are too often neglected by critics, despite several scenes devoted to her perpetual uprootedness in Enfance (1983; translated into English as Childhood), an unusually structured “autobiography” significantly often arranged into a dialogue between the octogenarian author and “herself” as a child—though the “identity” of her true conversation partner remains debatable, as do of course the fluctuating “identities” of all her, as the years go by, increasingly disembodied fictional voices. In any event, as well as (uncharacteristically) relating enigmatic childhood anecdotes, Sarraute typically conveys the ways in which certain words and phrases “hurt her.” Or perhaps, following her lead, we should dispense with the direct object and say, intransitively: “the ways in which certain words and phrases hurt.” Yet is hurting possible without a definite agent and a clear-cut victim or “patient” (taking this latter term in its etymological sense)? Sarraute’s phenomenology presupposes this unsettling intransitivity, at least partly, in any case to an extent far exceeding our traditional understanding of interrelational emotional causality.

Opening the pages of the Pléiade edition to the detailed biographical summary, one is immediately impressed by a tragic familial fact also related to biculturalism: Sarraute’s father, the ingenious chemist Ilya Tcherniak, and her mother, the popular Russian writer “N. Vikhrovski” (the pen name of Pauline Chatounowski), divorced when Natalia was only two years old. This event immediately brought the girl to Paris, where her mother remarried. By the next year, Natalia—become Nathalie—was attending pre-school on the rue des Feuillantines, at the edge of the Latin Quarter, not far from Luxembourg Gardens.

It should therefore not be surprising, at least to readers who have learned a few foreign languages, that many memorable pages of Childhood, and elsewhere, turn an extremely meticulous ear to pronunciation, such as to Sarraute’s father’s Russian “r” (audible when he was speaking French, a language that he had otherwise mastered) or to the way the girl’s tongue, lips and teeth move differently when she says the French word “soleil” as opposed to its Russian cog-nate, ‘“solntze.” Certain foreign phrases, for example the German “Nein, das tust du nicht” (“No, that you won’t do”), likewise puzzle the child. In Ouvrez (about which more below), an entire dialogue is devoted to the essentially school-learned, grammatically correct, yet occasionally unpronounced phonetic liaison between a word ending in a consonant and a subsequent word beginning with a vowel. Sarraute bases her gently sarcastic sketch on the simplest French phrase, “c’est” (“it’s”), juxtaposing it with a first-name, “Antonin.” Comic variants result from the different pronunciations of the two words together: “Cé Antonin,” “Cé Tantonin.” Another sketch investigates the hidden implications involved in strictly pronouncing “tu n’as qu’à . . .” (“you only need to. . .”), or, on the contrary, in appealing to colloquial sloppiness: “t’as qu’à,” “taka,” “taa . . . ka . . .” In L’Usage de la parole (1980; The Use of Speech), Sarraute devotes a compelling, implicitly candid essay to Chekhov’s dying words, spoken not in his mother tongue but rather in German: “Ich sterbe,” literally “I am dying.”

All languages, and thus notably French, are inherently “foreign” for Sarraute, by which I mean that the author of the unambiguously entitled Vous les entendez? (1972; Do You Hear Them?) and “Disent les imbéciles” (1976; “Fools Say”) concentrates on every syllable, every phoneme, of an expression, testing and retesting it from all angles until those rapid, precise, “invisible actions” that we sense inside us—those “pre-linguistic movements” that Sarraute calls “tropisms”—become perceptible, palpable. (In the life sciences, a tropism is an involuntary orientation in an organism, induced by an independent stimulus.) For Sarraute, this “tropismic substance” founds our existence and constitutes its genuine source. The term “foreign,” as applied to language, hence has an arresting extension. Language seems to be, for Sarraute, an all too human means of communication to which we only partly, imperfectly, impurely, accede; what interests her is that which remains ensconced beneath the linguistic surface: the not-yet-verbalized sensation or feeling. These underlying actions (or “movements”) initially engage spontaneous inner attraction or repulsion (a sort of primitive, pre-verbal “sympathy” or “antipathy”) and only at a much later stage, conscious intention, let alone intellection. Sarraute came to term these pre-verbal inter-personal “exchanges” the “sub-conversation” of her plays and dialogic prose. Her penetrating comprehension of phonetic nuance is surely something for which her precocious bi-, even quasi-tri-, and later almost-quadri-, lingualism accustomed her. And we spoke that afternoon of how she had adored learning Latin in French schools. . . .

* * *

Whence the following hypothesis: Because of Sarraute’s polyglotism, frequent moves, and broken childhood home, she very quickly learned to listen far beyond or—to use her favorite spatial preposition—“beneath” the social surface of discourse and to grasp what was really going on in the minds of her interlocutors. And this arduous task, for which she mustered all the resources of her body and exceptionally keen, analytical mind, is restaged minutely (even if fictionally transposed) in her prose and plays. She situates this “re-in-actment,” via writing, “beneath” the ebb and flow of the superficial daily reality that she, and we, normally observe. Interestingly, Sarraute admitted that every word in her writing is the “result” of a dramatic act. The nameless narrator of her work—the “writer,” in the final reckoning—indeed implicitly incarnates an initial incomprehension, as well as a stubborn willingness to survive in unstable, often secretly hostile, social surroundings. Intense analysis assures one’s self-defense.

Yet because of her radical skepticism with respect to the concept of a “personal identity,” Sarraute always dismissed—graciously in her conversation, vigorously in her essays—the interest of biography as a critical tool for comprehending her writing. It is nevertheless obvious that certain outstanding facts about her early life cast her relentlessly maniacal analyses of interpersonal relationships—based, after all, on material taken from the most banal deeds and common parlance of the quotidian—into a much different light. The renowned “impersonality” of her work can henceforth seem a courageous “objectification” of her own experiences of linguistic, emotional, familial, geographical, social, even racial uncertainty. Sarraute was Jewish and her father frequently suffered, professionally, from racial prejudice. Her intellectually challenging books become extremely moving, and unquestionably “down-to-earth,” when this autobiographical backdrop is recalled. Like a scientist (and she provocatively called herself a “realist” who seeks to measure “amorphous elements” lost, dissolved, imprisoned or smothered in the “magma” of everyday banality), Sarraute’s narrators aim for ever greater comprehension, both in detail and in scope. Could not this “objective,” “scientific” goal also represent an attempt to gain control over their constantly fragmented, dispersed, threatened lives? In Childhood in particular, but basically in all of her books, a social nexus of character-perturbing relationships is imaginable beneath the dialogues.

Be this as it may, Nathalie Sarraute was also steeped in the literature of her native Russia, a bond that she described several times to me that afternoon. The Age of Suspicion (first published as L’Ère du soupçon in 1956), a volume of essays which was soon perceived, by critics, as laying the theoretical foundation for the French “New Novel” (a grouping of writers and a collective appellation about which Sarraute was nonetheless extremely dubious), opens with a characteristically trenchant homage to Dostoyevsky’s psychological method, which she viewed as innovative. She had of course read The Brothers Karamazov and Notes from Underground in the original, even as she was able to read James Joyce, Henry Green, Joyce Cary, Ivy Compton-Burnett, and especially Virginia Woolf in English. (The genealogy of her own ideas about literature and “psychology”—a term she replaced by “psychisme,” an unsatisfactory substitute since theoretically, in her view, there is no coherent “psyche” to isolate and study rationally—includes the psycho-epistemological approaches implicit in certain, but not all, of the novels of Gustave Flaubert, Marcel Proust, Joyce, and Woolf. Sarraute notably eschews Freudian psychoanalysis.) This key essay, “From Dostoyevsky to Kafka,” was originally written in 1947, not long after she had finished her first novel (and second book), Portrait d’un inconnu (Portrait of a Man Unknown). Prefaced generously but also rather misleadingly by Jean-Paul Sartre, who called the book an “anti-novel,” Portrait of a Man Unknown had been drafted between 1940 and 1946, a period during much of which Sarraute—who refused to wear the yellow star—spent in hiding. “By the time the book finally appeared, in 1948,” she commented, “I had already long gone on to new projects.”

* * *

That afternoon, Nathalie Sarraute spoke at length of the publishing history of Portrait of a Man Unknown—first refused by Gallimard, the company that would, however, publish all her subsequent books, beginning with her third, Martereau (1953)—only because she wanted to express her sympathy with my own long wait between my American publisher’s original acceptance of my second collection of short stories and the book’s scheduled appearance. That we ventured at all onto this topic highlights her hospitality, disinterested curiosity and spontaneous empathy—personal qualities which touched many others besides myself yet which, strikingly, are much less present in her prose. As a writer, Sarraute focuses sharply, even grimly, on a fictional interlocutor’s concealed intentions. I had no desire to mention anything about myself to Sarraute, but she had read the brief bio appended to my article; and as she was pouring tomato juice, from a small bottle, into my glass, she was already inquiring about my own writing. Throughout our conversation, moreover, Sarraute proved to be much more interested in learning about my own life—and notably about my bilingual son, who was five years old at the time—than in expatiating on her career. She repeated three or four times an extraordinary phrase: “Oh, ça ne m’a jamais intéressée d’être ‘quelqu’un’, d’avoir un ‘moi’.” (“Oh, I have never been interested in being ‘someone,’ in having an ‘ego.’”)

After her death, reminiscences printed in French newspapers and magazines reiterated Sarraute’s affectionate inquisitiveness toward her afternoon visitors. Several admirers admitted their initial apprehension about meeting the author of such meticulous dissections of everyday social intercourse; often invited alone, as I had been, her visitors had imagined that their every utterance would be cut apart with the same razor-sharp scalpel that Sarraute wields in Tu ne t’aimes pas (1989; You Don’t Love Yourself) or in her other books. Such is the somber, relentless drive structuring many of her novels. This is not to say that they lack humor, a quality shining forth whenever difficult or dense passages are read aloud with theatrical finesse.

Yes, Sarraute knew how to make her guests feel at home in that book-lined parlor, serving them up an excellent Bloody Mary or the equivalent. Reclining slightly onto the cushions of the banquette, she would laugh, even tease a bit, and affectionately interrogate visitors who were inevitably much younger than her. She was as inclined to debate (with me, for example) the differences between her inter-personal “tropisms” and my subject-oriented “apperceptions,” between her emphasis on “sensation” and mine on “emotion,” as she was to discuss (also with me) bilingual first-names (a great-grandson had just been born), Anjou sweet white wines, and the practical problems of shopping and traveling. (She had recently returned from what must have been the last of her countless trips abroad, this time to London, where she had been invited to discuss her work at a French cultural institute.) At one point, someone called on the phone; she picked up the receiver, listened, said “yes,” laughing, and hung up without saying good-bye, explaining to me immediately afterwards that it was “an old and dear friend” inquiring if she were “busy,” and that with such a close friend you could have a perfectly frank relationship. She also spoke admiringly of the novels of Patrick Modiano, a writer from whom Sarraute might at first seem very distant; distant, that is, if one forgets that Modiano also obsessively explores the German Occupation, existential anguish, and uncertain identities in fictions which are invariably set before his own birth yet which, paradoxically, are unmistakably personal in tone. The play-director Simone Benmussa, in her remarkably deep-probing, intimately well-informed, yet no less rigorous and exacting Entretiens avec Nathalie Sarraute (1999), questions the author time and again about these apparent contradictions. What indeed is the connection between the intellectually vivacious old woman, who while conversing exudes such personal warmth and wholeness, and the author of novels devoted to exploring the “emptiness,” “incoherence” and “indeterminacy” of human beings? Asking Sarraute about her “feeling” or “sensation” of the “je,” the “I,” Benmussa receives these answers:

I have no feeling of having an identity. . . . Looking at myself from the outside, I know [what the ‘je’ is]. I am ‘me’, ‘je’ . . . whatever you want to call it. . . . But on the inside . . . there is no more ‘je’ . . . I cannot see myself . . . I cannot imagine for a single instant what you see of me. It’s simply impossible. . . . We see something compact inside ourselves—something with qualities and defects, with character traits that form a ‘personality’. Looking at ourselves from the outside, we usually find this ‘something’ to be likeable, pleasant. Yet if we place ourselves where I do [in my writings] . . ., we are in fact such immensities, and there are so many things going on, that—seen from the inside—there is no identity whatsoever.

Sarraute considered herself to be, not a “person,” but rather a “vessel of psychic states.”

* * *

During our initial phone conversation, Sarraute had mentioned a new book. “I’m almost finished with Ouvrez,” she explained that afternoon, “a series of short play-like sketches in which the protagonists are words. I work on the manuscript every morning, and I’m still making co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: The Voice behind the Prose

- Part 2: French Humor

- Part 3: Dreaming and Dailiness

- Part 4: Language Reaching Out

- Part 5: The Quest for “Life"

- Part 6: Myths and Mysteries of Eros

- Part 7: Mirrors and Prisms of Autobiography

- Part 8: The Life and the Work

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index