1

The Aesthetics of Function

James Marston Fitch

It is common in design circles to claim that architectural phenomena are enormously complex. Usually what this assertion means is that a building is made up of so many different kinds of systems and is subject to such a wide variety of technological, esthetic, and social constraints that it is often exceedingly difficult to resolve a design problem. The notion of architectural complexity, however, also applies to the relations between the built environment and society. Many different aspects of architecture and a variety of human needs and group processes are interconnected. For example, the visual qualities of architecture, its geometrical forms, the environmental control systems of buildings., the sheer provision of two-dimensional surfaces and three-dimensional spaces—all these aspects of architecture may become meaningful to people and influence their behavior. In the other direction, there are a great number of biological, psychological, and cultural needs that architecture and the environment have the capacity to satisfy. At the least, many of these needs can be satisfied through social mechanisms and social forms that architecture can help to organize and regulate. These needs are related to specific characteristics of the human organism, including man’s anatomical structure and physiology, his personality and unconscious mental life, his perceptual apparatus, his use of symbol systems for communication, and his dependence upon group interaction for civilized survival.

Fitch’s selection is an attempt to provide a conceptual framework that will alert the student of architectural phenomena to the many different ways in which the built environment and man are related. His argument is particularly directed against the traditional emphasis in architectural training and criticism on the visual qualities of buildings. Fitch counters this view by describing the linkages between the human being’s response to the environment and his full perceptual mechanism. The full perceptual mechanism includes not only the visual and auditory senses but the gustatory, olfactory, and haptic responses, and the sense of spatial orientation as well. This perspective leads Fitch to a definition of architecture as a “third environment” that mediates between the hazards of the natural world and of civilized society and the internal breathing, feeling, seeing, and hearing processes of man.

Two additional polemical thrusts underlie Fitch’s argument. One is the view, repeated in several selections in this book, that until basic anatomical and physiological needs are better satisfied through building designs, human societies cannot really afford the luxury of an interest in the esthetic properties of architecture. The second is the demand for an experimental architecture that will also be experiential, that is to say, that will be responsive to the full range of human needs and will call upon the total sensory capacity of the human organism.

A fundamental weakness in most discussions of aesthetics is the failure to relate it to experiential reality. Most literature on aesthetics tends to isolate it from this matrix of experience, to discuss the aesthetics process as though it were an abstract problem in logic.

Art and architectural criticism suffers from this conceptual limitation. This finds expression in a persistent tendency to discuss art forms and buildings as though they were exclusively visual phenomena. This leads to serious misconceptions as to the actual relationship between the artifact and the human being. Our very terminology reveals this misapprehension: we speak of art as having “spectators,” artists as having “audiences.” This suggests that man exists in some dimension quite separate and apart from his artifacts; that the only contact between the two is this narrow channel of vision or hearing; and that this contact is unaffected by the environmental circumstances in which it occurs. The facts are quite otherwise and our modes of thought should be revised to correspond to them.

Art and architecture, like man himself, are totally submerged in an exterior environment. Thus they can never be felt, perceived, experienced in anything less than multi-dimensional totality. A change in one aspect or quality of the environment inevitably affects our response to, and perception of, all the rest. The primary significance of a painting may indeed be visual; or of a concert, sonic: but perception of these art forms occurs in a situation of experiential totality. Recognition of this is crucial for aesthetic theory, above all for architectural aesthetics. Far from being based narrowly upon any single sense of perception like vision, architectural aesthetics actually derives from the body’s total response to, and perception of, its external physical environment. It is literally impossible to experience architecture in any “simpler” way. In architecture, there are no spectators: there are only participants. The body of architectural criticism which pretends otherwise is based upon photographs of buildings and not actual exposure to architecture at all.

Life is coexistent and coextensive with the external natural environment in which the body is submerged. The body’s dependence upon this external environment is absolute—in the fullest sense of the word, uterine. And yet, unlike the womb, the external natural environment does not afford optimum conditions for the existence of the individual. The animal body, for its survival, maintains its own special internal environment. In man, this internal environment is so distinct in its nature and so constant in its properties that it has been given its own name, “homeostasis.” Since the natural environment is anything but constant in either time or space, the contradictions between internal requirements and external conditions are normally stressful. The body has wonderful mechanisms for adjusting to external variations, e.g., the eye’s capacity to adjust to enormous variations in the luminous environment or the adjustability of the heat-exchange mechanism of the skin. But the limits of adaptation are sharp and obdurate. Above or below them, an ameliorating element, a “third” environment, is required.

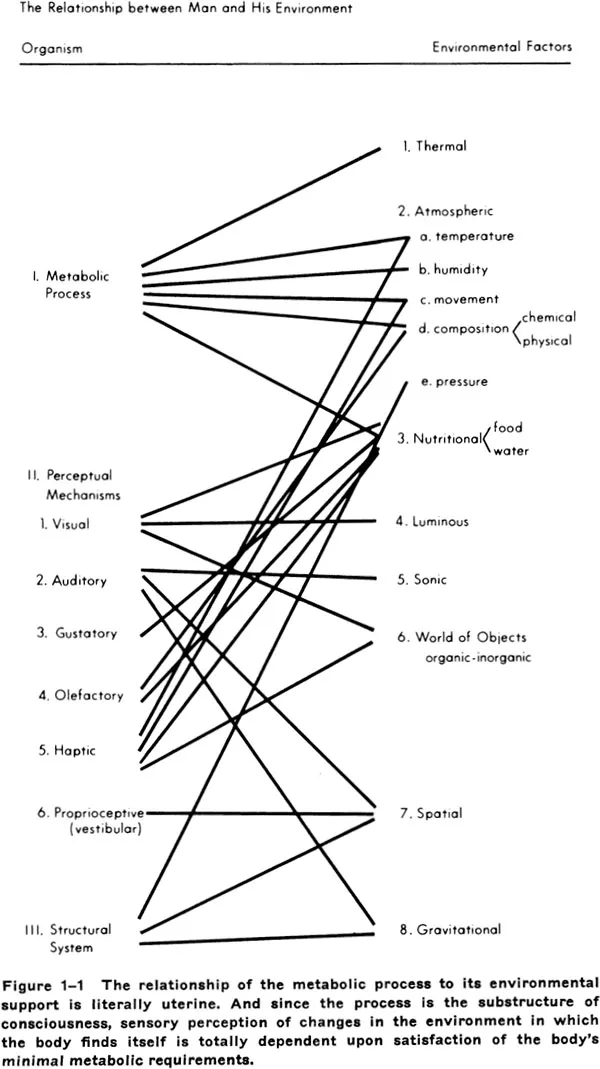

Before birth, the womb affords this to the foetus. But man, once born into the world, enters into a much more complex relationship with his external environment. Existence now is on two distinct levels, simultaneously and indissolubly connected, the metabolic and the perceptual. (Figure 1-1.) The metabolic process remains basic. It is at once a “preconscious” state and the material basis of consciousness. Many of life’s fundamental processes transpire at this level: heart beat, respiration, digestion, hypothalmic heat exchange controls, etc. Metabolic disturbance occurs only when the external environment begins to drop below the minimal, or rise above the maximal, requirements of existence. And sensual perception of the external environment comes into play only after these minimal requirements are met. (As a matter of fact, loss of consciousness is one of the body’s characteristic responses to environmental stress—drop in oxygen or pressure, extremes of heat and cold, etc.)

Metabolic process then is clearly the precondition to sensory perception, just as sensory perception is the material basis of the aesthetic process. But the aesthetic process only begins to operate maximally, i.e., as a uniquely human faculty, when the impact upon the body of all environmental forces are held within tolerable limits (limits which, as we have said, are established by the body itself). Thus, we can construct a kind of experimental spectrum of stress. The work of psychiatrists like Dr. George Ruff at the University of Pennsylvania establishes the lower end of this spectrum: sensory overloading is destructive, first of balanced judgments, then of rationality itself.1 But the other end of this spectrum proves equally destructive. Investigations of the effects of sensory deprivation, such as those carried on by Dr. Philip Solomon of the Harvard Medical School, indicate that too little environmental stress (and hence too little sensory stimulation) is as deleterious to the body as too much. Volunteer subjects for Dr. Solomon’s experiments were reduced to gibbering incoherence in a matter of a few hours by being isolated from all visual, sonic, haptic and thermal stimulation.2

Figure 1-1 The relationship of the metabolic process to its environmental support is literally uterine. And since the process is the substructure of consciousness, sensory perception of changes in the environment in which the body finds itself is totally dependent upon satisfaction of the body’s minimal metabolic requirements.

Psychic satisfaction with a given situation is thus directly related to physiologic well-being, just as dissatisfaction must be related to discomfort. A condition of neither too great nor too little sensory stimulation permits the fullest exercise of the critical faculties upon that situation or any aspect of it. But even this proposition will not be indefinitely extensible in time. As one investigator has observed in a recent paper (significantly entitled The Pathology of Boredom)3: “variety is not the spice of life; it is the very stuff of it.” The psychosomatic equilibrium which the body always seeks is dynamic, a continual resolution of opposites. Every experience has built-in time limits. Perception itself has thresholds. One is purely quantitative; the ear cannot perceive sounds above 18,000 cycles per second; the eye does not perceive radiation below 3,200 Angstroms. But another set of thresholds are functions of time: constant exposure to steady stimulation at some fixed level will ultimately deaden perception. This is true of many odors, of “white” sounds and of some aspects of touch.

Of course, even more important facts prevent any mechanistic equating of physical comfort with aesthetic satisfaction. For while all human standards of beauty and ugliness stand ultimately upon a bedrock of material existence, the standards themselves vary astonishingly. All men have always been submerged in the environment. All men have always had the same sensory apparatus for perceiving changes in its qualities and dimensions. All men have always had the same central nervous system for analyzing and responding to the stimuli thus perceived. The physiological limits of this experience are absolute and intractable. Ultimately, it is physiology, and not culture, which establishes the levels at which sensory stimuli become traumatic. With such extremes—high temperatures, blinding lights, cutting edges and heavy blows, noise at blast level, intense concentrations of odor—experience goes beyond mere perception and becomes somatic stress. Moreover, excessive loading of any one of these senses can prevent a balanced assessment of the total experiential situation. (A temperature of 120 degrees F. or a sound level of 120 decibels can render the most beautiful room uninhabitable.) But as long as these stimuli do not reach stressful levels of intensity, rational assessment and hence aesthetic judgments are possible. Then formal criteria, derived from personal idiosyncrasy and socially-conditioned value judgments, come into play.

The value judgments that men apply to these stimuli, the evaluation they make of the total experience as being either beautiful or ugly, will vary: measurably with the individual, enormously with his culture. This is so clearly the case in the history of art that it should not need repeating. Yet we constantly forget it. Today, anthropology, ethnology and archaeology alike show us the immense range of aesthetically satisfactory standards which the race has evolved in its history: from cannibalism to vegetarianism in food; from the pyramid to the curtain wall in architecture; from polygamy and polyandry to monogamy and celibacy in sex; from hoopskirt to bikini in dress. Yet we often act, even today, as if our own aesthetic criteria were absolutely valid instead of being, as is indeed the case, absolutely relative for all cultures except our own.

Our aesthetic judgments are substantially modified by non-sensual data derived from social experience. This again can be easily confirmed in daily life. It is ultimately our faith in antiseptic measures that make the immaculate white nurses, uniforms and spotless sheets of the hospitals so reassuring. It is our knowledge of their cost which exaggerates the visual difference between diamonds and crystal, or the gustatory difference between the flavor of pheasant and chicken. It is our knowledge of Hitler Germany which has converted the swastika from the good luck sign of the American Indians to the hated symbol of Nazi terror. All sensory perception is modified by consciousness. Consciousness applies to received stimuli, the criteria of digested experience, whether acquired by the individual or received by him from his culture. The aesthetic process cannot be isolated from this matrix of experiential reality. It constitutes, rather, a quintessential evaluation of and judgment on it.

Once in the world, man is submerged in his natural external environment as completely as the fish in water. Unlike the fish in his aqueous abode, however, he has developed the capacity to modify it in his favor. Simply as an animal, he might have survived without this capacity. Theoretically, at least, he might have migrated like the bird or hibernated like the bear. There are even a few favored spots on earth, like Hawaii, in which biological survival might have been possible without any modification. But, on the base of sheer biological existence, man builds a vast superstructure of institutions, processes and activities: and these could not survive exposure to the natural environment even in those climates in which, biologically, man could.

Thus man was compelled to invent architecture in order to become man. By means of it he surrounded himself with a new environment, tailored to his specifications; a “third” environment interposed between himself and the world. Architecture, is thus an instrument whose central function is to intervene in mans favor. The building—and, by extension, the city—has the function of lightening the stress of life; of taking the raw environmental load off man’s shoulders; of permitting homo fabricans to focus his energies upon productive work.

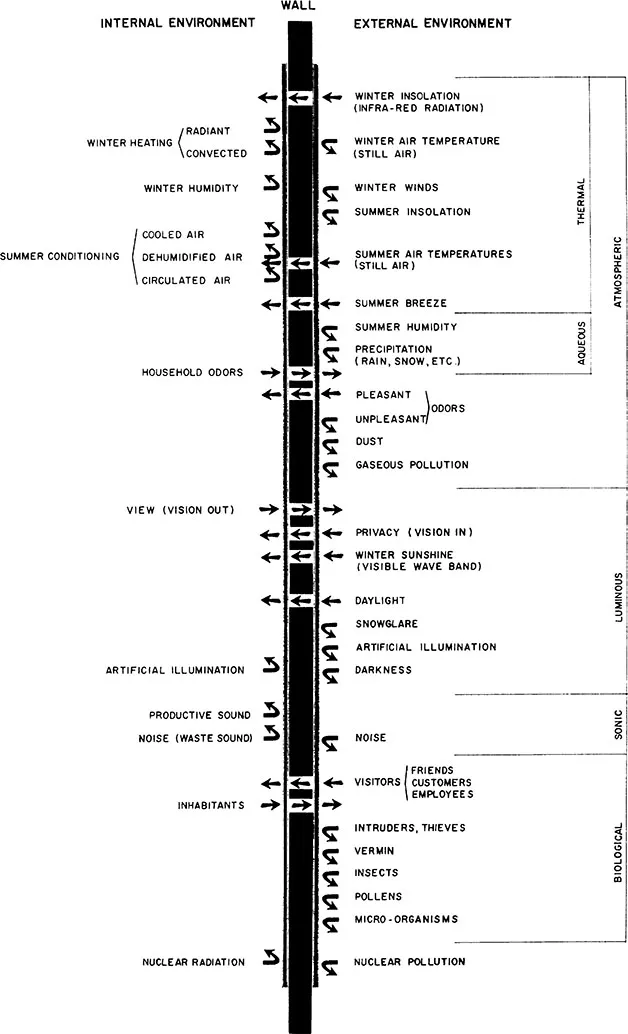

The building, even in its simplest forms, invests man, surrounds and encapsulates him at every level of his existence, metabolically and perceptually. For this reason, it must be regarded as a very special kind of container. (Figure 1-2.) Far from offering solid, impermeable barriers to the natural environment, its outer surfaces come more and more closely to resemble permeable membranes which can accept or reject any environmental force. Again, the uterine analogy; and not accidentally, for with such convertibility in the container’s walls, man can modulate the play of environmental forces upon himself and his processes, to guarantee their uninterrupted development, in very much the same way as the mother’s body protects the embryo. Good architecture must thus meet criteria much more complex than those applied to other forms of art. And this confronts the architect, especially the contemporary architect, with a formidable range of subtle problems.

All architects aspire to give their clients beautiful buildings. But “beauty” is not a discrete property of the building: it describes, rather, the client’s response to the building’s impact upon him. This response is extremely complex. Psychic in nature, it is based upon somatic stimulation. Architecture, even more than agriculture, is the most environmental of man’s activities. Unlike the other forms of art— painting, music, dance—its impact upon man is total. Thus the aesthetic enjoyment of an actual building cannot be merely a matter of vision (as most criticism tacitly assumes). It can only be a matter of total sensory perception. And that perceptual process must in turn have adequate biological support. To be truly satisfactory, the building must meet all the body’s requirements, for it is not just upon the eye but upon the whole man that its impact falls.

From this it follows also that the architect has no direct access to his client’s subjective existence: the only channels of communication open to him are objective, somatic. Only by manipulating the physical properties of his environment—heat, air, light, color, odor, sound, surface and space—can the architect communicate with his client at all. And only by doing it well, i.e., meeting all man’s requirements, objective and subjective, can he create buildings which men may find beautiful.

Figure 1-2 The building wall can no longer be considered as an impermeable barrier separating two environments. Rather, it must be designed as a permeable filter, capable of sophisticated response to the wide range of environmental forces acting upon it. Like the uterus, its task is the modulation of these forces in the interests of its inhabitants—the creation of a “third environment” designed in man’s favor.

The matter by no means ends here, however. The architect builds not merely for man at rest, man in the abstract. Typically, he builds for man at work. And this confronts him with another set of contradictions. For work is not a “natural” activity, as Hannah Arendt has brilliantly reminded us.4 Labor, according to her definition, is “natural” —that...