eBook - ePub

Objectives, Competencies and Learning Outcomes

Developing Instructional Materials in Open and Distance Learning

- 156 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Objectives, Competencies and Learning Outcomes

Developing Instructional Materials in Open and Distance Learning

About this book

This text offers a perspective on issues surrounding student learning by addresssing questions of quality and learning effectiveness across a broad and diverse range of courses, student populations and contexts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Objectives, Competencies and Learning Outcomes by Reginald Melton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Objectives, Competences and Learning Outcomes

The behaviourist approach to teaching and testing is based upon the way in which objectives are stated and used. It requires that objectives be expressed in terms of measurable student behaviour, indicating what students should be able to do in order to demonstrate that they have achieved the objectives specified. The intent is that students should achieve the standards set in full, rather than in part as so often happens with conventional teaching approaches. The philosophy behind the approach is simple yet compelling, namely that objectives stated in such a manner will provide teachers and learners with clear guidance as to what is expected of them, and will indicate in advance how student performance will be assessed.

Over the years behavioural types of objectives have emerged in a variety of different forms, and the intent in the first part of the book is to describe and compare three common types of objectives: behavioural and domain-referenced objectives, competences, and learning outcomes. In discussing the nature of behavioural and domain-referenced objectives we will highlight their background. This is important, for it is also the background from which competences and learning outcomes have emerged, and tells us a great deal about the nature of competences and learning outcomes. In the process of reviewing these different types of objectives, we will examine their strengths and weaknesses, and this will lead us naturally in the final chapter to a consideration of ways in which the development of natural links between competences and learning outcomes can most importantly provide natural links between education and training and can facilitate movement between academic and vocational routes within secondary and further education.

Chapter 1

Behavioural and domain-referenced objectives

This chapter begins with a review of the background from which behavioural and domain-referenced objectives emerged, and is followed by a discussion of how one might set about identifying such objectives for education and training purposes. It will be seen that from the very beginning the behaviourist approach strove to develop a scientific approach to teaching and testing, and as more was learnt about it the automatic reaction to emerging problems was to try to develop techniques that were even more scientific. Subjectivity and human judgement were frowned upon, and the whole drive was towards increased objectivity. However, as the field developed there was increasing recognition that human judgement has an important part to play in all aspects of the approach and that decisions are subject to a wide variety of human factors. This change in perception is reflected in the final section of the chapter, where the concern is with placing behavioural and domain-referenced objectives in perspective.

The background from which behavioural and domain-referenced objectives emerged

The foundations to the behaviourist approach to teaching and testing can readily be traced back to Tyler (1934), who suggested that educational objectives should be:

defined in terms which clarify the kind of behavior which a course should help to develop among the students… This helps to make clear how one can tell when the objective is being attained, since those who are reaching the objective will be characterized by the behavior specified.

Tyler (1949) subsequently went on to describe how educational objectives might be derived, and how they might be used to determine the type and order of educational experiences that would be most likely to ensure the realization of the stated objectives. As such, Tyler indicated how behavioural objectives could be used to guide the work of designing and developing the whole process of teaching and learning, and in so doing he provided the foundations upon which the behaviourist approach was to be constructed.

The growing perception of the design and development of teaching and learning as a science owed much to Skinner (1938) who was already well known for his study of behaviours in organisms. Skinner (1957) believed that his philosophies concerning learning in animals could be extended to learning in human beings, and he went so far as to suggest that ‘concepts and methods which have emerged from the analysis of behavior… are the most appropriate to the study of what has traditionally been called the human mind.’

During the 1960s the behaviourist movement achieved widespread popularity, particularly in the United States, with educators such as Tyler (1964), Mager (1962) and Popham (1969) firmly of the view that efficient and effective teaching was dependent on student objectives being expressed in unambiguous behavioural terms and on teaching being designed to help students to achieve the specified objectives. Mager’s approach, that was widely adopted in the 1960s, was to suggest that objectives should be expressed in a behavioural type of format which identified what students should be able to do in order to demonstrate that they had achieved the stated objective. To avoid ambiguity he suggested that such ‘behavioural objectives’ should incorporate three basic elements: a statement of the level of performance to be demonstrated, an indication of the conditions under which the performance should occur, and details of any constraints that might apply. Here is an example of an objective produced according to this format:

Given the attached names of 20 concepts and the related, but randomized, list of 20 definitions (conditions), you should be able to correctly identify definitions for at least 18 of the concepts (level of performance) within a period of 5 minutes without referring to related instructional materials (constraints).

One of the main problems with such objectives is what Macdonald-Ross (1973) called ‘a specificity problem’:

if you only have a few general objectives they are easy to remember and handle, but too vague and ambiguous (to be helpful), but if you try to eliminate the ambiguity by splitting down the objectives, then the list becomes impossibly long.

The development of domain-referenced objectives was seen as a way of overcoming this problem. Such objectives contained two basic elements: a statement of the objective in fairly broad behavioural terms and a domain description providing details of the way in which achievement of the objective might be measured. An example will illustrate the characteristics of such objectives:

Objective

Given any ten pairs of two-digit numbers, you should be able to compute the product of at least nine out of ten pairs correctly within a period of 5 minutes.

Sample Test Items

| 12 × 11 = | (11) (15) = |

| 16 × 13 = | (18) (14) = |

| 17 × 18 = | 13 times 16 = |

| 14 . 12 = | 19 multiplied by 19 = |

| 10 . 10 = | the product of 15 and 11 = |

Item Characteristics

- Test items to measure mastery of the objective will be selected at random from a matrix containing all possible pairs of two-digit numbers, that is, from a matrix of 8,100 possible items.

- Each test will contain the six item formats that are included in the above sample, and the formats used will be distributed in the same manner between test items.

This example is much more explicit than the typical domain-referenced objective, but it illustrates how judgement is brought to bear in deciding whether students have achieved a particular objective, even when the objective appears to be expressed in very explicit terms. You will see that the example includes a statement of the objective to be achieved:

Given any ten pairs of two-digit numbers, you should be able to compute the product of at least nine out often pairs correctly within a period of 5 minutes.

It also contains sample test items and details of item characteristics that define the domain of test items that might be used to measure whether or not students have achieved the stated objective. At first glance it would appear that the ten pairs of numbers used to measure student achievement of the objective might be selected from a domain of 8,100 different pair combinations (assuming that the reverse presentation of any given pair of numbers produces two different combinations). In fact, since six alternative forms of presentation are possible, the domain actually contains 48,600 items. It follows that the type of test proposed is based on an extremely small sample of 10 items, and as such will simply provide an estimate of the probability of the student having mastered the domain as a whole.

Most domain-referenced objectives are expressed in much broader terms than the one discussed here, and a more typical example is contained in Chapter 2 in the form of an ‘element of competence’ (Figure 2.2). It will be seen that ‘performance indicators’ and ‘range statements’ are used in this latter case to describe the related domain of test items. In fact, a variety of formats have been developed for domain-descriptions by those such as Guttman (1969), Bormuth (1970), Anderson (1972) and Hively et al. (1973). However, most designers of instructional materials are quite content to use a range of sample test items to provide an indication of the type of test items that might be used to measure student mastery of the stated objective.

Identifying objectives for education and training purposes

As far back as the 1940s procedures were being developed for identifying course aims and objectives. Around that time Tyler (1949) was arguing that those concerned with determining the aims and objectives of teaching should take into account the needs of students and society, the opinions of subject-matter specialists, and the educational and social philosophies of the institutions concerned. This is still generally accepted.

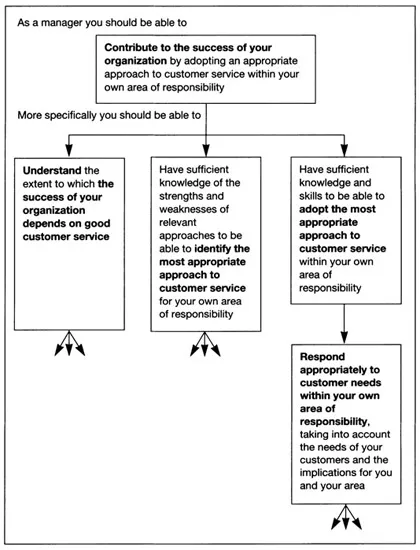

Once broad aims have been identified these need to be translated into more explicit, behavioural-type objectives. During the 1960s a hierarchical form of analysis was widely adopted for this purpose, with those such as Gagne (1965) and Krathwohl and Payne (1971) describing it in very similar terms. The process started with broad statements of aims, and involved the breaking down of each broad aim in a sequence of stages into increasingly specific aims and objectives, thus identifying in the final stage the prerequisites, in terms of behavioural objectives, upon which achievement of each ultimate aim depended. A flow diagram, used to help identify objectives for a module on customer service in a course on management, is included here (Figure 1.1) to illustrate the process.

Figure 1.1a Deriving objectives for unit on customer services in a management course

Figure 1.1b Deriving objectives for unit on customer services in a management course

Although the prerequisite objectives identified at the bottom of the hierarchy are not expressed in terms of domain-referenced objectives, they could readily be transformed into that format if it was considered desirable. The main point to note is that the prerequisite objectives are much more explicit than the broad statements of aims at the top of the hierarchy, and could be used for assessment purposes. It is for this reason that assessment in the past tended to focus on how students perform against prerequisite objectives, since this can be measured in a fairly objective manner.

Other approaches to the identification of objectives were developed by those such as Flanagan (1954), Gilbert (1962), and Holsti (1969), but it was the hierarchical approach that gained greatest popularity, and which is still widely used today.

One of the great risks in attempting to express objectives in an explicit format is the tendency to focus attention on objectives that can easily be expressed in a measurable form and to ignore those that appear to be difficult to measure; in the early days this often led to the identification of more trivial objectives. Bloom’s work in classifying different types of objectives was therefore important in alerting educationists to the ways in which different types of objectives might be expressed. In the Cognitive Domain of the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (1956) Bloom identified six categories of objectives concerned with the acquisition of knowledge and intellectual skills; these are summarized below in terms of what students should be able to do:

demonstrate their knowledge of information provided (eg, by recalling facts, strategies, principles or theories)

demonstrate understanding of information provided (eg, by expressing this in their own terms)

apply what they have learned (eg, rules, methods, principles or theories applied to new situations)

analyse information provided (eg, by distinguishing between factual and hypothetical statements)

synthesize information (eg, by putting new ideas together in new ways)

evaluate what is put in front of them (eg, by identifying weaknesses in arguments, principles or theories).

In conjunction with others (Krathwohl et al., 1964) Bloom subsequently developed the Affective Domain of the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, identifying and categorizing within this a range of objectives concerned with the development of interests, attitudes and values. Whereas student performance against cognitive objectives could normally be measured by means of paper tests, performance against affective objectives needed a broader range of strategies – including the use of questionnaires, interviews and personal observation – and often much more subjective judgement. It is still useful to reflect on these different categories when identifying different types of objectives, but, as we shall see in reviewing the nature of competences and learning outcomes in the chapters that follow, many other types of objectives are of great interest to those currently involved in education and training.

Placing behavioural and domain-referenced objectives in perspective1

As with any approach to teaching and training, the behaviourist approach to the specification and achievement of standards has both strengths and weaknesses, and the following are some of the key issues that need to be taken on board in adopting any of the strategies so far considered.

The importance of human judgement

In the early days the breakdown of broad aims into more specific objectives was perceived as offering a scientific approach to the identification of objectives, but it is now well recognized that, although the process provides a logical way of deriving and setting objectives, human judgements are brought to bear at every stage in the process. This point is best taken on board by making every attempt to ensure that any group charged with the identification and derivation of objectives inclu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Series editor's foreword

- Introduction

- Part I Objectives, Competences and Learning Outcomes

- Part II The Design and Development of Related Instructional Materials

- References

- Subject index

- Name index