![]()

PART I

The early modern Jewish ghetto

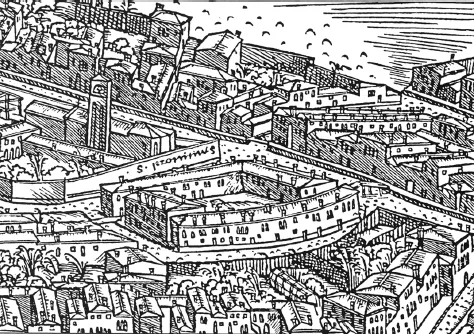

View of Venice by Jacopo de’ Barbari, 1500. Detail of the sestiere Cannaregio showing the area of the Ghetto, with the walled monastery of San Girolamo (left). Courtesy of Samuel Gruber

![]()

1

GHETTO

Etymology, original definition, reality, and diffusion

Benjamin Ravid

Introduction

At the outset, it must be acknowledged that the major impulse for segregating the Jews initially came from the Christian Church. Therefore, in order to understand that development, one must briefly consider the special attitude of Christianity toward Judaism. After the original Judeo Christians broke with Judaism by rejecting Jewish law and accepting pagans directly into their midst without first converting them to Judaism and thereby establishing Christianity as a separate religion, Christianity adopted a hostile “sibling rivalry” toward those who remained Jews. On a theological level, this was not – as is so often assumed – simply because the Jews were considered responsible for the death of Jesus according to the Gospels and especially the verse found only in the Gospel of Matthew 25:25, “His blood be upon us and on our children.” Rather, it was because Christianity based itself and its legitimacy upon the Old Testament and claimed to be the true Israel, while condemning the Jews who were perceived as erring by stubbornly following the rabbinic interpretations of the Bible rather than the new true Christian exegesis. The classical Christian attitude to Judaism was summed up by the Witness Theory of the church father Augustine (354–430), which held that the Jews should not be killed but rather preserved in a position of inferiority in order to testify to their rejection by God, who had chosen Christianity as the true Israel and the inheritor of the biblical blessings while condemning the Jews to receive the curses enumerated in the Bible. With the expansion of Catholicism throughout Europe, this approach to the Jewish question came to be accepted by the secular authorities who, if they permitted Jews to reside in their realm, subjected them to a widely varying range of prohibitions and restrictions.

Jewish quarters had existed in the Hellenistic pre-Christian Mediterranean world, and as they spread throughout Christian Europe during the Middle Ages, they were designated various names in diverse languages. Some designations consisted of the local word for street, quarter, or district together with an adjective indicating that Jews lived there, while others did not reflect a Jewish presence.1

Although sometimes the origins of a Jewish quarter can be attributed to a specific act of legislation or administrative decree, often – especially in earlier periods – it remains veiled in the twilight zone of undocumented history. Various reasons have been proposed for the emergence of these Jewish quarters. The simplest explanations cite the natural tendency for groups of foreigners or individuals engaged in the same profession to settle together. Also, if the authorities of a given locale were trying to attract immigrants for commercial or economic reasons, as an inducement for them to come, they might be given a designated area in which to settle, sometimes even surrounded by a wall and perhaps also a gate or gates for their safety. More specifically, in addition to wishing to live close to relatives and friends, Jews also desired to be near the synagogue and other community institutions, as well as stores selling food prepared according to their religious rites and other items needed for their religious observances. And for their general solidarity and defense, Jews no doubt felt more comfortable living in close enclaves.

Yet the more that one looks at the phenomenon of the pre-modern Jewish quarter, the more one recognizes the validity of the astute observation of Haim Beinart, made over thirty years ago, that “more is unknown than known about the issue of Jews dwelling in separate quarters in the Middle Ages.”2

Most basically, one must differentiate between the general term “Jewish quarter” and the term “ghetto,” that originally indicated a very specific kind of Jewish quarter that we will define below as a compulsory, segregated and enclosed Jewish quarter. Modern scholars have very often employed the two terms indiscriminately without differentiating between voluntary areas of residence in which a substantial number of Jews lived together and compulsory, segregated, and enclosed Jewish quarters.3 To complicate matters, in places where it is known that walls and gates existed, it is not always known when they were established, whether all Jews and only Jews were allowed to reside inside the enclosure, or whether the gates were locked for the entire night to segregate the inhabitants or rather for their security and could be opened when desired. To sum up, one can conclude that although compulsory, segregated and enclosed Jewish quarters were not completely unknown in Christian Europe before the sixteenth century, for some had been established in Christian Spain and one of the best-known ones was that established in Frankfurt in 1462, clearly they did not represent the norm, and one should not assume that any Jewish quarter belonged to that category without conclusive proof.4 Certainly, the few that did could never have been referred to by contemporaries as ghettos, because the association of the word “ghetto” with a Jewish quarter commenced in Venice in 1516.

The word “ghetto” came into being to designate the copper foundry of the Venetian government, il ghetto (sometimes spelled gheto, getto, or geto) where bronze cannon balls were cast, from the root gettare, to cast or to throw, encountered in English words such as eject, jet, and trajectory. Eventually, an adjacent island was used to dump waste products from the ghetto, and it became known as the Ghetto Nuovo, the new foundry, to distinguish it from the area of the foundry that then became known as the Ghetto Vecchio, the old foundry.5 However, in the fourteenth century, when the foundry was no longer able to meet the needs of the Venetian state, it was sold, and the area became the site of modest houses mainly inhabited by weavers and other petty artisans. Until the year 1516, the word “ghetto” was used only to refer to that area, and therefore all usages referring to ghettos as Jewish quarters prior to that date are anachronistic.

Subsequently, during the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the word “ghetto” came to be used for all compulsory, segregated and enclosed Jewish quarters on the Italian peninsula. Then, in the nineteenth century, after those Jewish ghettos had been abolished (with the exception of that of Rome),6 “ghetto” came to be used to refer in a new sense to designate dense areas of Jewish settlements in Europe and North America that were not compulsory, segregated and enclosed and often consisted of poor immigrants, and then by extension to such quarters of other minority groups. Although used to refer to Afro-American quarters in the United States before the Second World War, the usage of the term “ghetto” during the Holocaust led to a much greater awareness of the term, which then came to be used primarily to refer to Afro-American quarters, and then those of other minority groups.7 Understandably, the simultaneous extended usages of the word “ghetto” in different senses created a blurring of the very important distinction between voluntary quarters and compulsory, segregated, and enclosed ones that reflected completely different attitudes on the part of the government.

The ghettos of the early modern Italian peninsula and Frankfurt

During the Middle Ages, the Venetian government acquiesced in the presence of a few individual Jews in the city of Venice, but except for the brief period from 1382 to 1397, never authorized Jews to settle as a group.8 However, it allowed Jews to live on the Venetian mainland, especially in Mestre, across the lagoon from Venice. When in 1509 the enemies of Venice united and invaded the Venetian mainland and advanced to the edge of the lagoon in 1509, the government granted the inhabitants of the mainland, including Jews, refuge in the city. Then, in 1513, primarily because of the utility of the Jews as moneylenders since the Catholic Church prohibited Christians from lending money to fellow Christians at interest, the government issued a 5-year charter to a Jewish moneylender from Mestre, allowing him and his associate to operate small-scale pawnshops at controlled rates of interest in Venice itself. But many Venetians were bothered by the fact that Jews now resided freely all over the city. The clergy preached against the Jews, especially at Easter time when, due to the nature of the holiday, anti-Jewish sentiment tended to intensify, and demanded their expulsion. In 1515, around Easter time, the government proposed to relegate the Jews to the island of Giudecca (whose name, in this case, has nothing to do with Jews9) but no action was taken because of their objections. However, in the following year, 1516, again around Easter time, the Venetian Senate enacted, despite strong Jewish objections, a compromise between the new freedom of residence and the previous state of exclusion and required all Jews to dwell on the island called the Ghetto Nuovo.

The preamble to the legislation of 29 March recollected that in the past, various laws had provided that no Jew could reside in the city for longer than 15 days a year. However, out of necessity and because of the most pressing circumstances of the times, Jews had been permitted to live in Venice, primarily so that the property of Christians that was in their hands (i.e., the pledges in the pawnshops) would be preserved. Nevertheless, it continued, no God-fearing Venetian wished that they should live spread out all over the city in the same houses as Christians, going where they pleased day and night, and committing, as was known to all and was too shameful to relate, many detestable and abominable acts to the gravest offense of God and against the honor of the well-established Venetian republic.

Therefore, the legislation continued, all Jews then living throughout the city and those who were to come in the future were immediately to go to live together in the Ghetto Nuovo. In order for this to be done without delay, its houses were to be evacuated at once, and as an incentive for the owners to comply, the Jews (who since 1423 had been forbidden from purchasing or acquiring real estate in the Venetian state) moving in were to pay a rent one-third higher than the current rate, with that additional amount to be exempt from the decima tax. Furthermore, to prevent Jews from going around all night, gates were to be erected on the side of the Ghetto Nuovo facing the Ghetto Vecchio and also at the other end. These two gates were to be opened in the morning at sunrise and closed at sunset by four Christian guards who were to live there alone, without their families, and be paid by the Jews. The two sides of the Ghetto Nuovo that overlooked the small canals were to be sealed off by high walls, and all direct access from the houses to the canals, which served as the main route of communication and transportation in Venice, was also to be eliminated. Thus, the Jewish quarter known as the ghetto of Venice came into being.10

Now, to summarize, this Senate legislation contained three basic provisions:

•The new Jewish quarter was compulsory – every Jew had to live within it.

•It was segregated – no Christians were allowed to live inside it.

•It was enclosed by walls and a gate or gates that were locked at night and remained so until the morning.

Despite the attempts of the Jews to ward off se...