1

Evaluation: A Semantic Magnet

Evaluation:

The action of appraising or valuing (goods, etc.); a calculation or statement of value; = valuation.

The action of evaluating or determining the value of (a mathematical expression, a physical quantity, etc.) or of estimating the force of (probabilities, evidence, etc.).

—Oxford English Dictionary, 1933 (1978)

As early as classical antiquity, scholars were summoned to Court to become counsellors to the Prince. Aristotle was hired by King Philip of Macedon as the youthful Alexander’s teacher in statecraft. During the siege of Syracuse, the Roman legionnaires were forced to protect themselves from Archimedes’ burning mirror and catapults. The tendency has continued in Europe’s nation states. Heeding a request from King Christian IV, the prominent astronomer Tycho Brahe took residence at the Court in Copenhagen to read the monarch’s horoscope in order to aid the King in the crafting his foreign policy. Members of the Nobel family, in their efforts to invent and supply the Czar with modern weapons, made several tests of explosive substance on the ice of the Neva river in St. Petersburg.

Public sector evaluation is a recent addition to a great chain of attempts by princes to use the brainpower of scholars and scientists to further the interests of the state. The services requested from evaluation experts are, of course, completely different from the ones hinted at in the examples cited above. Evaluation scholars are asked to provide retrospective assessments of the administration, output and out-come of government measures in order to effect self–reflection, deeper understanding, and well–grounded decisions on the part of those who are in charge of government operations. Discarding the hackneyed political notion that honorable intentions are enough, evaluation is predicated upon the opposite idea that good practices and solid results are what really count. Evaluation implies looking backward in order to better steer forward. It is a mechanism for monitoring, systematizing, and grading government activities and their results so that public officials in their future–oriented work will be able to act as responsibly, creatively, and efficiently as possible. The interventions of the modern state are so extensive, their execution so complicated, and their potential consequences so far–reaching that science and social research are needed to monitor operations and establish impacts.

However, systematic evaluation is not for contemporary princes alone, but can also be called upon by the political opposition, the professions, the citizenry, or the clientele of government programs. For political scientists, the political opponents’ and the citizens’ perspectives on evaluation are of particular concern.

Careful retrospective assessment requires systematic data collection, data analysis, and source documentation. In addition, pertinent criteria of merit and standards of performance about how well the intervention must do on these criteria are needed, because evaluation is a normative enterprise.

Evaluation Defined

“Evaluation is the process of determining the merit, worth, and value of things.” These words by Scriven (1991:1) capture the basic, natural meaning of the term evaluation. Evaluation is the process of distinguishing the worthwhile from the worthless, the precious from the useless.

Evaluation is a key analytical procedure in all disciplined intellectual and practical endeavors. While acknowledging that the process of determining the merit, worth, and value of things permeates every domain of thought and practice, in the present work evaluation will be delimited to suit the demands of public service and governmental affairs. For the purpose of this book, I propose the following definition:

Evaluation = df. careful retrospective assessment of the merit, worth, and value of administration, output, and outcome of government interventions, which is intended to play a role in future, practical action situations.

This definition of evaluation is controversial. Evaluation is circumscribed in numerous ways. Actually, the term evaluation has attracted so many different meanings that we may call it a semantic magnet (Lundquist 1976:124). It has come to signify almost any effort at systematic thinking in the public sector. It is easy to agree with the very first sentence in Carol Weiss’ early textbook Evaluation Research (1972): “Evaluation is an elastic word that stretches to cover judgments of many kinds.”

Since evaluation comes in many guises, I shall try to compare in more detail other scholarly definitions of evaluation with the one proposed here. The purpose of the exercise is to put my own definition into a larger perspective. I shall start with the subject matter of evaluation.

Evaluation Concerns Government Interventions

Since evaluation is a truly general analytical process, it can be applied to any area of social endeavor. A special thing in the present context, however, is that evaluation is limited to government interventions only, that is, politically or administratively planned social change, like public policies, public programs, and public services.

Contemporary public interventions cover substantive as well as process–oriented programs (Lundquist 1990). Substantive measures concern diverse functional domains such as energy, environment, natural resources, land use, housing, social welfare, health, transportation, economic development, and many other fields of endeavor. It also includes foreign policy, an area left entirely untouched by systematic evaluation (Vasquez 1986).

Process–oriented interventions—administrative reform—refer to ideas and measures directed at the organization and function of public administration itself (Petersson and Söderlind 1992:7ff). Administrative reform is concerned with management by objectives versus detailed process–oriented management, decentralization, new budgeting systems, changes in local administration, and other institution–building processes. A central problem in modern administrative reorganization is which institutional arrangements are used and ought to be used in implementation of public policies and programs: regulatory agencies stacked with neutral and competent executive officials, personnel appointed on political merits, execution through municipalities, corpo-ratist arrangements, professionals, client involvement, or contracting out to private business (overview in Lundquist 1985).

It goes without saying that evaluation embraces the assessment of substantive as well as process–oriented government interventions. Evaluation is targeted at all kinds of public sector activities.

Evaluation is Focused on Administration, Outputs, and Outcomes

As defined here, evaluation is not concerned with the entire policy cycle, but only with the back end of it. To clarify this idea, I shall introduce systems thinking, which is so prevalent in political science study of public administration.

Political scientists tend to view public administration as a system (see figure 1.1). A system is a whole the component parts of which are dependent upon each other. In its most rudimentary form, a system consists of input, conversion, and output in the following fashion:

FIGURE 1.1

The Simple System Model

In the field of public administration, the general–systems notion is applied to the civil service, which is viewed as a system. It could be one separate government agency, but also a conglomerate of different organizations. The agencies or conglomerates could be at any level, for instance at the global, the interregional, the national, the intraregional, or the municipal level. The input to an agency from the environment, particularly from its principal (e.g., the government), may be funds with some strings attached to their use, written instructions, oral support or criticism, and appointed people. Within the agency, funds, people, and instructions are coordinated and converted into something else. The conversion is what is going on in the agency. Output is what comes out of the agency.

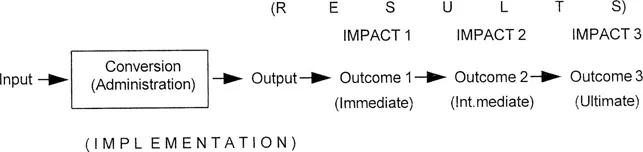

In public policy studies, the conversion stage of the general systems model is roughly equivalent to administration, and an outcome phase is often tacked to the output stage of the general system model. By output is meant phenomena that come out of government bodies in the form of, for example, prohibitions, enabling procedures, grants, subsidies, taxes, exhortation, jawboning, moral suasion, services, and goods. Outcomes are what happen when the outputs reach the addressees, the actions of the addressees included, but also what occur beyond the addressees in the chain of influence. We may distinguish between immediate, intermediate, and ultimate outcomes. Another term for outcomes is impacts. Results will be used as a summarizing term for outputs and outcomes. Results may also indicate either outputs or outcomes. The term implementation usually covers conversion and output. The reasoning is summarized in figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2

The System Model Adapted to Government Intervention Evaluation

Let me illustrate this with an example. Some years ago the Swedish government instituted a program to help refugees from the civil war in Afghanistan, who lived in camps in Pakistan. To this end, the government allocated funds to the Swedish International Development Agency, abbreviated SIDA. SIDA struck an agreement with the International Red Cross in Geneva, which promised to funnel the money to the National Red Crescent in Pakistan. For the funds, the Red Crescent was instructed to buy tents and blankets from local dealers, and provide the equipment to the refugee camps. In the camps, the local Red Crescent branch was expected to put up the tents, and distribute the blankets to the refugees. Then, refugees were supposed to use the tents and blankets in order to alleviate their plight.

To qualify as an evaluation, a study of the Help–to–Afghani–Refugees Program must concentrate on either the outcome (if the refugees were actually using the tents and the blankets and if that alleviated their plight), the output (the distribution of tents and blankets through the local Red Crescent), or the administration (what happened to the funds once they had reached the SIDA through the purchase of blankets and tents by Pakistani authorities). Admittedly, outcome evaluation may be considered more important than output or conversion evaluation. However, I do not want to equate evaluation with outcome evaluation. The concept, as defined here, includes concern with administrative processes and output as well. In the refugee case, for instance, everybody can see that administration is a long process with several levels of authority involved.

The limitation to outcomes, outputs, and administration excludes studies assessing ex post the merits and drawbacks of features in the policy formation phase. For instance, actual or past policy formation can be assessed against such evaluative criteria of merit as comprehensive and reliable information base or participation by various affected interests. One may evaluate measures on the books, using such dimensions of merit as comprehensibility or consistency with other programs. In this context, however, such studies will not be reflected upon.

One additional clarification is probably justified. The limitation to administrative processes, outputs, and outcomes is not concerned with explanatory factors in evaluation. If the evaluation sets out to explain what influenced variations in administrative procedures, outputs, and outcomes, my definition allows for explanatory factors to be drawn from anywhere. It would be abjectly inappropriate to delimit the concept of evaluation with respect to the determinants that may be discerned.

Now, I have ventured to justify the delimitation of the subject matter of evaluation to “administration, outputs, and outcomes of government interventions.” In the next section, I shall address what it means for evaluation to be “retrospective”.

Evaluation is Retrospective

Evaluation is retrospective assessment of public interventions. Prospective appraisals (i.e., scrutinies of courses of action considered but not yet adopted even as prototypes), are not included in my definition. Also this limitation is controversial, particular in the North American context. Leading theoretists argue that prospective assessment—ex ante assessment, forethought evaluation, needs assessment, analysis for goal– setting—does belong to evaluation. To them, evaluation becomes an umbrella, covering all kinds of analyses of, in, and for public intervention. Is it reasonable to let “evaluation” refer to almost any intellectual effort in the public sector? Cases of this large perspective on evaluation can be taken particularly from economists, who perform cost–benefit and cost–effectiveness analyses of potential, future options, maintaining they practice evaluation. Also Rossi and Freeman (1989:18) adopt this large perspective when they maintain: “Evaluation research is the systematic application of social research procedures for assessing the conceptualization, design, implementation, and utility of social intervention programs” (italics mine; also Anderson and Ball 1978:3, 11, 15ff).

“If planning is everything, maybe it’s nothing?” Aaron Wildavsky (1973) ironically wondered two decades ago on the then strongly fashionable fad, planning. Can the same question be raised today, when ex ante assessment is included in evaluation? Of course, it is both futile and foolish to legislate about the use of a word. But if evaluation is allowed to embrace all kinds of analysis in political and administrative life, will not the concept become too diluted? Here, perhaps, we face another instance of the semantic magnetism of the word evaluation.

The major argument against including ex–ante assessments in evaluation is drawn from the origin and history of evaluation research. The demands of the early evaluation movement for empirical data on policy and program results emerged in opposition to the prevailing emphasis on analysis of planned interventions. If evaluation is allowed to embrace even planning, this significant historical line of conflict will be obscured.

Hence, in this context I have confined evaluation to after-the-fact assessments. Such assessment concerns adopted interventions in the sense of ongoing or terminated policies, programs, program ingredients, and the like, no matter whether they are veterans or recently introduced small–scale prototypes. Before–the–fact analysis of potential, not-yet-adopted interventions, however, is not included in evaluation in my usage in the present book.

Evaluation is Assessment of Ongoing and Finished Activities

Sometimes evaluation is restricted to ongoing activities, leaving out assessment of finished policies and programs. This quite narrow perspective is clearly discernible in David Nachmias’s textbook Public Policy Evaluation (1979:3f):

One method that can reduce the number of erroneous decisions is the formal scientific approach to knowledge.… Viewed from the scientific perspective, policy evaluation research is the objective, systematic, empirical examination of the effects ongoing policies and public programs have on their targets in terms of the goals they are meant to achieve.

Actually, the narrow perspective on the subject matter of evaluation is a commonplace in American and Canadian literature. According to Rutman, “program evaluation refers to the use of research methods to measure the effectiveness of operating programs” (1980:17). Wholey et al. write: “Evaluation assesses the effectiveness of an ongoing program in achieving its objectives” (1970).

Indubitably, ongoing interventions clearly belong to the subject matter of evaluation. They may even constitute the core subject of public sector evaluation. But should evaluation b...