eBook - ePub

Comparative Psychology of Invertebrates

The Field and Laboratory Study of Insect Behavior

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Comparative Psychology of Invertebrates

The Field and Laboratory Study of Insect Behavior

About this book

First Published in 1997. The papers in this volume on invertebrate behaviour, predominantly ant behaviour, are presented as a tribute to T. C. Schneirla and to his theoretical and experimental contributions to our understanding of the development and evolution of behaviour. His emphasis on development also brought to the fore new questions, many of which are addressed in this volume. Advances in technical instrumentation for research will be useful in reformulating these old questions in new and significantly constructive programs for responsible research. The theoretical contributions of Schneirla will continue to prove an important facilitation of those new research techniques.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Comparative Psychology of Invertebrates by Gary Greenberg,Ethel Tobach in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section I

Persistent Issues in the Comparative Study of Behavioral Evolution and Development

The Role of Controversy in Animal Behavior

What I saw when I looked at the famous duck-rabbit was either the duck or the rabbit, but not the lines on the page—at least not until after much conscious effort. The lines were not the facts of which the duck and rabbit were alternative interpretations.

(Thomas S. Kuhn, 1979, p. ix)

As a philosopher of science, T. C. Schneirla understood the important distinction between facts and their interpretation. He was clearly no stranger to controversy, as Piel pointed out in his introductory essays to a book honoring Schneirla (1970) and to the published version of the inaugural Schneirla conference (1984). His involvement in controversy—scientific, philosophical, cultural and political—is part of the reason that Schneirla “was not popular, not celebrated in the gatherings of psychology in his time. Schneirla was not in the mainstream” (Piel, 1984, p. 13). A pertinent example is the intellectual battle he waged with both the European ethologists and the American operant psychologists (Piel, 1970).

In retrospect one can well wonder why divergent views held by the ethology and the American psychology schools led to such intense controversy. That is because few realize that controversy, in part, is a recurring component in collective scientific research, albeit a terribly inefficient and quite unnecessary complication. We can appreciate this complication if we are willing, but another problem was recognized by Anderson (1988, p. 18): “To end controversies, scientists must first understand them, but scientists would rather do science than discuss it.” More optimistically, Latour (1987, p. 62) stated: “We have to understand first how many elements can be brought to bear on a controversy; once this is understood, the other problems will be easier to solve.”

To understand scientific controversy, we first have to understand how science operates, a topic normally given scant attention by scientists—just as Anderson emphasized. Schneirla clearly understood how science is actually more a process than a series of accomplishments. By contrast, biology textbooks extoll the accomplishments of scientists, largely ignore scientific process, and omit mention of controversies that may have preceded given accomplishments.

Psychologists, who receive extensive exposure to the history, methodology and philosophy of science, even as undergraduates, are usually surprised when they learn that these topics are nearly absent from the formal education of biology students in this country. Two decades ago I checked dozens of college catalogues across the country and found that courses in the above subjects were notably absent from undergraduate biology curricula, while nearly universally required for psychology undergraduates.

Physics is apparently in little better shape than biology, leading Theocaris and Psimopoulos to comment (1987, p. 597): “The hapless student is inevitably left to his or her own devices to pick up casually and randomly, from here and there, unorganized bits of the scientific method, as well as bits of unscientific methods.”

The problem is not a new one. Ludwik Fleck (1935/1979) recognized the presumed disparity of approach between those in the “hard sciences” and those in the “soft sciences” when he wrote (p. 47): “. . . thinkers trained in sociology and classics . . . commit a characteristic error. They exhibit an excessive respect, bordering on pious reverence, for scientific facts.” Neither did Fleck leave those in the “hard sciences” untouched; he wrote (p. 50) that the error of natural scientists consists of “an excessive respect for logic and in regarding logical conclusions with a kind of pious reverence.”

Unfortunately, most ignore the great amount of accumulated thought (wisdom) that has been published in past decades, including notions about scientific process. While others have treated parts of that process in depth, a brief review of the overall collective process can be included here, summarized from more complete accounts published earlier (e.g., Wenner, 1989, 1993; Wenner & Wells, 1990).

Scientific Process

Unless science students are thoroughly inculcated with the discipline of correct scientific process, they are in serious danger of being damaged by the temptation to take the easy road to apparent success. . . . [They] should understand all the subtle ways in which they can delude themselves in the design of observations and the interpretation of data and statistics. (Branscomb, 1985, pp. 421, 422)

My interest in an analysis of this process began when Patrick Wells and I, along with our co-workers, became embroiled in a major scientific controversy in the mid to late 1960s (e.g., Wells & Wenner, 1973; Wenner & Wells, 1990). That controversy (the question of a “language” among honey bees) continues to this day.

We felt at the time that the bee language controversy should not have emerged from our test of that hypothesis. The relevant scientific community not only rejected our alternative interpretation but also ignored or summarily dismissed the anomalous results we had obtained, for the most part without even repeating the critical experiments that had yielded our results. Instead, Maier’s Law (Maier, 1960, p. 208) prevailed: “If facts do not conform to the theory, they must be disposed of.”

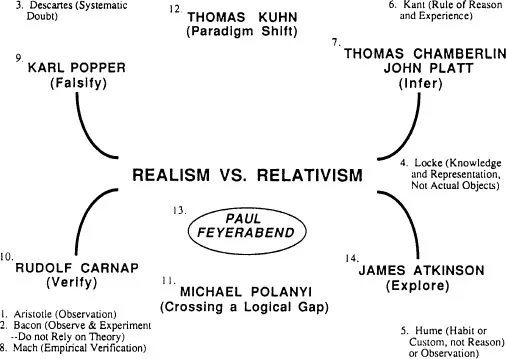

Consequently, we studied the history, philosophy, sociology, psychology and politics of science for two decades in an attempt to decipher what had transpired in the controversy that erupted as a result of our test of the language hypothesis (see Wenner & Wells, 1990). From that study, we recognized that scientific progress occurs (as indicated above) collectively and inefficiently by an unconscious group application of a definable method. We gradually formulated a diagram for our perception of this process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The collective scientific process and how portions of it have been perceived through time, with each portion having had its advocates. For each sequence on any one collective research project, the complete process starts in the lower right-hand corner and progresses clockwise around the diagram, as the scientific community expands the scope of its inquiry (some steps may be omitted by practitioners). Movement around the diagram can stall (paradigm hold, see ), at which time progress plateaus. The numbers represent a chronology of contributions to formation of the diagram. See text for further explanation.

The diagram is simple in principle. A new research trend begins (lower-right hand corner—exploration approach) when an individual recognizes (not merely observes) an important anomaly in nature while engaged in “normal science” (e.g., Kuhn, 1962/1970; Polanyi, 1958). Unconsciously, perhaps, that individual has moved from a state of “realism” (“knowing” what reality is) to “relativism” (an interpretation previously held to be “fact” is now suspect). The scientist then “creates an image” (Atkinson, 1985), forms an alternative explanation for evidence at hand and attempts to convert others to the same point of view.

If others can be convinced of the new interpretation, the scientist’s view is reinforced (incipient “vanguard science”—Fleck’s term, see below), moves back to the “realism” mode and attempts to verify the results (verification approach), a necessary but not sufficient part of the overall scientific process. When others can verify the results, many scientists can become committed to the new interpretation. A new research emphasis and protocol may then arise in a broader portion of the scientific community (“vademecum science”—Fleck’s term, see below; also later termed “normal science” by Kuhn).

Unfortunately, much of animal behavior research during the past three decades has relied on verification alone (a partial view of the scientific process and only a portion of the “logical positivism” or “logical empiricism” school). That is, testing each hypothesis was not considered necessary in much of animal behavior research whenever a large body of evidence supported a given hypothesis (e.g., Wenner & Wells, 1990, pp. 204, 234). Animal behaviorists are not alone; scientists in general are reluctant to test their hypotheses (e.g., Mahoney, 1976). Such an attitude, of course, was responsible for “cold fusion” and other debacles in chemistry and physics (e.g., Asimov, 1989; Huizenga, 1992; Rousseau, 1992; Taubes, 1993).

During the 1960s and 1970s, researchers in ecology (e.g., critiques by Dayton, 1979; Loehle, 1987) and in psychology (e.g., critique by Mahoney, 1976) adopted another rather narrow approach (moving further clockwise around the diagram); they insisted that research be molded into an appropriate “null hypothesis” (falsification) protocol. The implicit rationale: If a premise cannot be proven false, then it is likely true or has some “probability” of being true (“realism” school).

In part, Thomas Kuhn’s influence (anomalies emerge and eventually hypotheses become rejected, even without application of the formal null hypothesis approach) gradually forced psychologists to abandon their former comfortable stance. However, Schneirla had earlier perceived the weakness of that “working hypothesis” (e.g., Chamberlin, 1890/1965) approach, as phrased by Tobach (1970, p. 239): “He rejected logical positivism and operationism as bases for scientific inquiry and opened the way to a dynamic, holistic approach based on process.” Ecologists continue to demand conformity to the null hypothesis approach (Dayton, 1979; Loehle, 1987).

In 1890, Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin (upper right corner of the diagram) recognized the weakness of an overreliance on verification (“ruling theory,” in his terms) and/or on falsification (attempting to falsify a “working hypothesis,” as phrased by Chamberlin). He advocated application instead of “The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses” (inference approach), employing “crucial” experiments designed to provide mutually exclusive results. In that approach, scientists continually pit hypotheses against one another and attempt to falsify all of them during experimentation. After additional evidence is in, new alternative hypotheses are generated that might explain known facts and other pertinent information (e.g., Platt, 1964).

Only rarely does one find a scientist who can move from one approach to another with ease, as Claude Bernard, Louis Pasteur and Schneirla seem to have done, and as Feyerabend (1975) suggested in his famous phrase, “anything goes.” Duclaux (1896/1920), biographer of Pasteur, recognized another root problem with respect to “objectivity” and experimental design for those who attempt to use standard procedure when he wrote: “However broadminded one may be, he is always to some extent the slave of his education and of his past.” Four decades later, Fleck (1935/1979, p. 20) formed much the same conclusion: “Furthermore, whether we like it or not, we can never sever our links with the past, complete with all its errors.”

Bernstein summarized succinctly the dichotomy between realism and relativism (1983, p. 8):

The relativist not only denies the positive claims of the [realist] but goes further. In its strongest form, relativism is the basic conviction that when we turn to the examination of those concepts that philosophers have taken to be the most fundamental . . . we are forced to recognize that in the final analysis all such concepts must be understood as relative to a specific conceptual scheme, theoretical framework, paradigm, form of life, society, or culture.

Ludwik Fleck, Overlooked Sage

Ludwik Fleck was a medical doctor in Poland in the 1930s and an expert on syphilis and typhus, expertise that kept him from being killed in concentration camps during WWII. While earlier studying the history of changes in attitude toward syphilis through time, he recognized the tentative nature of scientific “fact” and published a monograph in 1935, entitled Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact.

Many of the points covered therein parallel notions advocated by those in the Schneirla school.

Thomas Kuhn wrote a foreword to the 1979 translation of Fleck’s book, in part to acknowledge his indebtedness to the work (having read it in German before publication of his own classic 1962 work) and in part to explain that the volume contained much that he had missed earlier. Kuhn wrote (1979, p. x): “Though much has occurred since its publication, it remains a brilliant and largely unexploited resource.” Kuhn also recognized that, rather than grasping the full implication of Fleck’s message during his early reading (relying on his “rusty German” as he put it), he had focused primarily on “. . . changes in the gestalts in which nature presented itself, and the resulting difficulties in rendering ‘fact’ independent of ‘point or view.’”

While writing our book, Patrick Wells and I did not know of Fleck’s perceptive analysis of scientific process, but our thoughts nevertheless had converged with his on many issues, particularly in his sections on epistemology.

Realism and Relativism Schools of Thought

Realism. The dubious notion that one can “know” reality was challenged repeatedly in Fleck’s treatise. He also recognized that scientists become too committed to hypotheses. Fleck (1935/1979) wrote (p. 84): “Observation and experiment are subject to a very popular myth. The knower is seen as a kind of conquerer, like Julius Caesar winning his battles according to the formula ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.’” And (p. 84): “Even research workers who have won many a scientific battle may believe this naive story when looking at their own work in retrospect.” Later Fleck commented (p. 125): “. . . the [generated] fact becomes incarnated as an immediately perceptible object of reality.”

The notion that “fact” has not necessarily been gained emerges from Fleck’s statement (p. 32): “The liveliest stage of tenacity in systems of opinion is creative fiction, constituting, as it were, the magical realization of ideas and the interpretation that individual expectations in science are actually fulfilled.”

Fleck’s awareness of the essence of Duclaux’s statement (above) is evident in his own statements (p. 27): “Once a structurally complete and closed system of opinions consisting of many details and relations has been formed, it offers enduring resistance to anything that contradicts it,” and (pp. 30, 31): “The very persistence with which observations contradicting a view are ‘explained’ and smoothed over by conciliators is most instructive. Such effort demonstrates that the aim is logical conformity within a system at any cost . . .” Neither was Fleck blind to social constraints in the conduct of research (p. 47): “. . . . Social consolidation functions actively even in science. This is seen particularly clearly in the resistance which as a rule is encountered by new directions of th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Series Editors’ Foreword

- Preface

- Section I. Persistent Issues in the Comparative Study of Behavioral Evolution and Development

- Section II. Social Organization in Ants

- Section III. Social Parasitism in Ants

- Section IV. Recent Research Issues

- Contributors

- Species Index

- Name Index

- Subject Index