- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

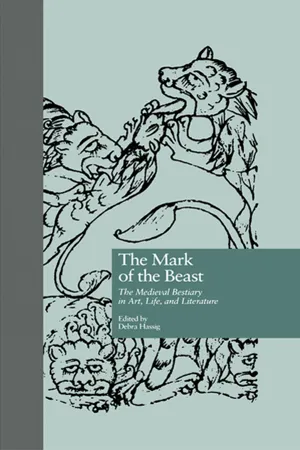

About this book

The medieval bestiary was a contribution to didactic religious literature, addressing concerns central to all walks of Christian and secular life. These essays analyze the bestiary from both literary and art historical perspectives, exploring issues including kinship, romance, sex, death, and the afterlife.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Mark of the Beast by Debra Hassig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Medieval & Early Modern Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Social Realities

The Lion, Bloodline, and Kingship

Margaret Haist

The lion is the most ubiquitous of the bestiary animals, and is also one of the relatively few to carry strong associations beyond the bestiary, especially in medieval heraldry. Often positioned first and described in the bestiaries as the "king of beasts," it is interesting to consider the relationship between the bestiary characterization of the lion and contemporary notions of kingship. This essay will explore this relationship, beginning with Old Testament interpretations of the lion emphasized in the Physiologus that later provided a useful model for contemporary notions of pure bloodline, kingly virtues, and just rule. Although evidence for royal patronage of bestiaries is inconclusive, it is suggested here that the bestiary lion entry addressed ideas of immediate concern to readers, who, if not themselves monarchs, were certainly living under monarchial rule. Most importantly, connections between the bestiary, heraldry, and contemporary views of kingship show how the lion as a symbol accrued new meanings over time through the skillful manipulation of both texts and images.

In the ninth-century Bern Physiologus, the opening miniature accompanying the earliest extant lion entry depicts Jacob blessing the lion of the tribe of Judah above a frieze of paired animals (figure 1).1 The accompanying text first proclaims the lion the king of beasts and then summarizes Jacob's blessing according to Genesis 49.2 Turning to Genesis directly, Jacob's blessing emphasizes the prophecy that Judah and his direct bloodline will lead the tribe until it produces the ruler whom the whole world awaits:

Juda is a lion's whelp:

To the prey, my son, thou art gone up:

Resting thou has couched as a lion,

And as a lioness, who shall rouse him?

The scepter shall not be taken away from Juda,

Nor a ruler from his thigh,

Til he come that is to be sent,

And he shall be the expectation of nations (Gen. 49:9-10).

To the prey, my son, thou art gone up:

Resting thou has couched as a lion,

And as a lioness, who shall rouse him?

The scepter shall not be taken away from Juda,

Nor a ruler from his thigh,

Til he come that is to be sent,

And he shall be the expectation of nations (Gen. 49:9-10).

This passage affirms the importance of bloodline and implies that keeping it uncontaminated will maintain the strength required to fulfill the ultimate prophecy, which, according to medieval interpretation of this passage, was the triumph of Christ.3 As we shall see, this idea is reinforced in the Bern Physiologus image as well as the text through allegorical comparison of Judah to the lion by reference to the idea of generation.

In the Bern illumination, the lion is positioned on a hillock above all of the other animals, representing on one level the animal world ruled by the king of beasts and on another "all nations" awaiting their supreme king. The particular species illustrated stand for different categories of animals subsequently described in the Physiologus, including domestic animals (cattle), exotic beasts (bears), and other quadrupeds (deer). Each animal type is represented by a matched pair rather than a single animal—the deer are thus rendered as a stag and a doe—which suggests sexual pairing, reproduction, and species continuity, in harmony with the Genesis passage. That is, the use of distinct animal types and the representation of paired species allegorically suggests the preservation of bloodline condoned in Genesis 49. In this, the Judah image is also related to both the iconography and meaning of representations of the Flood, in which animals are depicted two-by-two as a means of preserving the species, following God's instructions to Noah (Gen. 9:15-19).4

Although the lion pictured here is clearly identified in the text as the lion of the tribe of Judah, he also represents Christ, the culmination of Judah's bloodline. This identification is reinforced in the three subsequent lion images in the Bern manuscript (ff. 7v, 8), which picture the lion erasing his tracks with his tail, sleeping with his eyes open, and reviving his dead whelps; as allegorical figures of Christ's incarnation, death, and resurrection, respectively.5 Most important among these is the visual and verbal explication of how the lion's whelps are born dead and then revived after three days by their father, just as Christ was revived after three days by Our Father (f. 8).

In the Bern manuscript, the three miniatures depicting the specific lion habits seem to form a series apart from the Judah illumination, and in fact, the Judah image drops out entirely in the later bestiaries as emphasis shifts to the resurrection allegory. However, this image is important and worthy of careful scrutiny because it describes the point at which Old Testament prophecy and Christ's sojourn on earth intersect. It is also true that although the specific iconography is not repeated in the later bestiaries, ideas expressed therein are nevertheless incorporated in various ways, to be discussed below.

This first lion in the Bern rhysiologus represents Judah himself, to whom Jacob speaks, but he is also a manifestation of Jacob's prophecy, which according to medieval Christian interpretation is Christ's appearance on earth and ultimate triumph over evil. This is suggested by the rubric directly under the illumination, which indicates that the lion is the king of all beasts (Est leo regalis omnium animalium et bestiarum), thus connecting the lion's position in the animal kingdom to that of Christ as King of Kings,6 and in turn, to earthly kingship. It is also true that the presence of the halo suggests a Christ identification for the human figure, who is revealed as Jacob only if the viewer reads the text.7 Like the lion, the human figure also carries a double identification as the fusion of the Old Testament (as Jacob) and the New Testament significance of Jacob's prophecy (Christ).

In addition to the rubric, the idea of kingship is signaled by the mountain on which the lion stands. That is, Isaiah, speaking of the ascendency of Judah to Jerusalem, refers to the "holy mountain of the Lord" (Is. 2:1-3). According to the Physiologus and later bestiaries, the lion loves to roam in the mountains, just as the mountain is God's seat on earth, forming another parallel between natural and sacred history.8 This idea helps reinforce the lion's identification as Christ, linking the Old Testament to the New; the mountain is the site of God; therefore the lion (as Christ), assumes the mountain position. Thus, the link between the figure of the lion with bloodline and kingship was established at very early date in the Physiologus, and this connection continued to be strengthened with the development of the later bestiaries.

The early twelfth-century bestiaries continued the theme of bloodline in the lion entries, albeit with different pictorial emphases. Laud Misc. 247 is a particularly interesting example.9 While the Bern Physiologus devotes separate miniatures to the lion sleeping with open eyes—compared to the ever-vigilance of Christ—and reviving the whelps, Laud Misc. 247 conflates these two subjects in a single miniature (figure 2). A pair of lions lie at the base of the folio with open eyes, while above them, the lion parents hold a dead whelp between them. The lion on the right is licking the cub's nose, while the left lion appears to blow life-giving breath, as indicated from the wavy lines issuing from the mouth. The reviving lions are positioned above the "sleeping" lions as a sign of their greater importance, and indeed the resurrection allegory became the focus of bestiary lion imagery from the late twelfth century onwards. Finally, it is interesting to note that above the image is a long list of all of the animals subsequently treated in the bestiary, beginning with the lion (leo). It is as though the frieze of animals pictured in the Bern Physiologus image has been replaced by the written word, still representing a gathering of all of Creation under the care of the lion/Christ (figures 1, 2).

The sleeping lions in Laud Misc. 247 are worth closer inspection in light of the Physiologus' emphasis on the Genesis passage, which still accompanies the image. First of all, there are two lions rather than just one. It is also notable that the "sleepers" are stretched out side by side. Perhaps this pair of lions sleeping together represent Judah and his lioness as described in Genesis 49, while simultaneously referring to the theme of resurrection. Thus, God rouses, or resurrects, not only his son (as allegorically depicted above the "sleepers") but also the tribe of Judah, including the faithful who inherit the tribe's legacy through Jesus Christ. Layered onto this is the idea of generation of family line, which in Judah's case culminates in the birth, death, and resurrection of Christ, as summarized in the lion revival scene and which in turn signifies the resurrection of all Christians at Christ's second coming.10

In Laud Misc. 247, then, the lion iconography has maintained the emphasis on typological associations inspired by the connections between the lion's nature and Old Testament prophecy concerning the coming of Christ as well as New Testament ideas about his resurrection. However, during the later twelfth century, an interesting text addition was made to the lion entries that suggests a shift in focus from strictly typological concerns to more contemporary ones. The additional text describes the lion's treatment of his enemies as represented by the relevant passage in the St. Petersburg Bestiary: "Around men, the lion is one with nature and is not unnecessarily angered. Rational men should heed this example, and not allow themselves to be angered and oppress the innocent, because the law of Christ directs that even the guilty should go free."11 The text goes on to explain how the lion spares those who prostrate themselves before him.

The new text addition was accompanied by important pictorial changes that complemented the newly-introduced, merciful dimension of the lion's character. The most obvious of these was the direct illustration of the lion sparing prostrate men, as observable in the Ashmole Bestiary (f. 10), the Cambridge Bestiary (...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Abbreviations

- Figures A-K

- Part 1. Social Realities

- Part 2. Moral Lessons

- Part 3. Classical Inheritances

- Part 4. Reading Beasts

- Appendix: List of Bestiary and Physiologus Manuscripts

- Contributors

- Index of Creatures