A certain theoretical model is generally referred to in order to explain the barriers to vertical mobility between professional groups. Since it explains, from the viewpoint of socialization theory, how social inequality is reproduced from the parents’ generation to that of the children, it is called the Reproduction Model. It relates the unequal distribution of social privileges such as education, income, prestige, and power to the professional position of the father, which usually determines the social position of the family and which influences both parents’ views on education. Thus influenced by parental values, the socialization milieu of the family disposes the children to acquire attitudes and values which either help or hinder their success at school and their careers (see Aldous, Osmond, & Hicks, 1979, p. 239).

Reproduction of Social Inequality Through Socialization

Many sociological mobility analyses have demonstrated the existence of probability barriers and, in this respect, can be cited in support of the Reproduction Model. However, the empirical results are less convincing in the case of socialization studies which have examined the relationship between parental values and class membership or the relationship among children’s attitudes, parental orientations, and the system of social inequality (Bargel, 1973; Erlanger, 1974; Bertram, 1976; 1981; Zängle, 1978; Steinkamp, 1980).

Still, these criticisms need not be interpreted as a falsification of the Reproduction Model. Accordingly, in this chapter I shall use them as the basis for a critical discussion of four distinctive contributions to the development of the Reproduction Model.

Melvin Kohn (1969; 1973; 1977; 1981) has shown that the father’s professional orientation is determined not only by professional position, income, and education but by his working conditions, such as the work’s complexity level, the extent of control, and the extent of routinization, which are just as important for professional values and values in general. In contrast to most socialization studies, which have examined only class membership, or rather the unequal distribution of privileges, the Reproduction Model also takes into account the concrete working situation of the parents.

Lawrence Kohlberg (1969) has demonstrated that, in spite of the large number of naturalistic socialization studies that have been carried out, only small correlations between parents’ and children’s outlooks can be obtained. Kohlberg suspects that this low correlation is caused, on the one hand, by the failure of these studies to represent empirically and appropriately the considerable theoretical differences in the various models of family socialization and, on the other hand, by the prevalence of ad hoc theories. In the analysis of the Reproduction Model, the selection of the parent and child variables must, therefore, be founded on their relation to the “professional world” and must be plausible, so that the selected behavioral indicators are really those which influence the behavior of the adults concerned.

Urie Bronfenbrenner (1973) has indicated that family socialization can take place only in the framework of family interaction, i.e., in the context of the child’s living environment. Until now, research in socialization has been largely confined to analysis of the mother-child relationship. However, in the framework of the Reproduction Model, the father plays a decisive role as the mediator of socio-cultural values. Consequently, the social inequality theory described above requires an analysis of the family triad of father-mother-child. The object of this analysis must not be limited to the investigation of individual outlooks but must include the family’s relationship structure.

Finally, in my own work (Bertram, 1981) I have indicated that the Reproduction Model assumes that the socio-cultural values which arise from differing socio-structural living and working conditions are transmitted to the individual in the framework of family interactions. Empirical research concerning this hierarchical relationship among socio-structural working conditions, interaction-relationships, and individual action or personality is most adequately carried out within the framework of a multiple-level model, in which the different levels of socio-structural living and working conditions, family role-relationships, and individual action are integrated. For this research the structure of levels is the crucial part of the Reproduction Model. Moreover, one must not attempt to examine the indicators and variables of each level individually, but must instead reconstruct the relationship pattern of the variables on each level. Above all, the whole model, not only its parts, must be examined since a comprehensive examination of the model is needed for estimating its validity. In other words: “The object of research on the transmission of values in the family has generally not been to demonstrate a similarity that was assumed to exist” (Kohn, 1982, p. 1)·

The Empirical Model and the Variables

With these multi-level features of the Reproduction Model in mind, we now turn to the two topics of social inequality and individual moral development. In what follows I shall differentiate among the individual level, the family interaction level, and the socio-structural level.

The Individual Level

The analysis of children’s personalities measures cognitive variables, such as abstraction capabilities (Vygotski’s concept formation test), role-taking (Flavell), intelligence (Raven), and moral orientations, with the aid of a questionnaire (Kemmler) about moral judgment. This questionnaire for 8- to 11-year-old children is comprised of twelve dilemma-stories with four alternative answers, each of which represents a specific level of moral judgment according to Jean Piaget’s theory. In addition, a social attitude test (Joerger) has been applied to measure social maturity, also on the basis of Piaget’s concept.

The relevant cognitive variables here are concept formation, intelligence, and role-taking, all of which are involved in work tasks whose complexity is an essential characteristic of working conditions and of professional position. The theoretical relevance of these variables and the consistency of these personality characteristics should be obvious (Jencks, 1979; Eysenck, 1980), but the selection of moral judgment preferences may at first be surprising. There seem to be several reasons for this selection. Since not only the political orders but also the economic and professional systems of society are subject to profound changes, concrete political views or concrete professional orientations can hardly be the basis for the thesis of the Reproduction Model.

The scope of the moral judgment concept is not concerned with whether someone prefers an authoritarian or a democratic social order; rather, it is concerned with why the individual attends to different structures of social order. Therefore, in considering social and economic changes, we can retain the Reproduction Model of social inequality, as long as it allows us to analyze the socio-cultural reproduction of heeding rules from the parents’ generation to the children’s. With Piaget’s and Kohlberg’s models of moral judgment levels, there is also the question of an integrative model, in which previously unrelated theoretical principals of respect for rules are brought together in a hierarchical order.

Piaget’s and Kohlberg’s attempts to logically systematize the several clearly distinguishable types of respect for rules is especially significant if one asks which specific types of respect for rules are typical of which socio-cultural and professional contexts. That is, we may hypothesize that professions with complex working conditions, broad scope for decision-making, and few routine tasks contribute to individual self-direction and to moral autonomy as understood by Piaget (cf. Kohn, 1969, pp. 35-36). Should this hypothesis be empirically confirmed, then one might (using the cognitive-developmental model of moral judgment) relate the reproduction of social inequality to changes in society and its structure.

The Level of Interaction Relationships

Although there have been few previous attempts to analyze family triads from a socialization theory perspective, remedying this lack was not the central concern of the study, so we assessed the parents’ personalities by using Cattell’s 16 PF test. In doing so, we followed Cattell’s assumption that individual personality factors demonstrate action-forming or situation-deciding interaction strategies. In addition, the concrete parental values were measured by Kohn’s scales of self-direction versus conformity. Other variables were family size, living-space size, and other similar characteristics of family structure. With these variables, forty-five in all, we attempted to construct empirical, clearly-differentiated levels and theoretically profound relationship patterns.

The Levels of Social Structure

Owing to Kohn’s broadly empirical orientation, the empirical analysis of socio-structural influence carried out within the framework of the Reproduction Model is relatively straightforward. Under the influence of Blauner’s (1966) alienation theory, Kohn distinguishes among three essential aspects of working conditions: the extent of authority given to make independent decisions (control of other people’s work); the amount of routine work entailed (frequency and repetition of completed work); the complexity of the work (dealing with data, things, or people). These are aspects which determine the extent of autonomy. Kohn himself has shown that aspects of work are themselves influenced by the structure of the working organization (bureaucratic vs. unbureaucratic).

Kohn merely examines whether the father’s values, which correlate with his professional position as an indicator of a society’s class structure, can be related to his concrete working conditions. However, the Reproduction Model requires a precise empirical analysis of the relationship between class (hierarchy of professional positions), working organization, and working conditions. The hitherto unsatisfactory correlations between class membership and children’s or young people’s values, which led until now to severe criticism of the Reproduction Model, can be caused by the fact that working conditions vary only partially with class membership, and the working organization does not vary with it at all. In such a case one could expect the validity of the Reproduction Model to be present only where class membership, working-organization, and working conditions converge in accordance with the Reproduction Model.

The Integrated Model

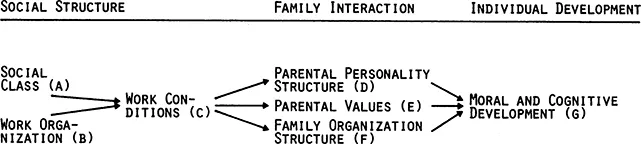

Figure 1 illustrates the integrated model with each of its three levels, along with the variables which represent them. This causal model of social reproduction is a further differentiation of the general Reproduction Model of social inequality through socialization. On the socio-structural level, it corresponds to Kohn’s model and assumes that the socio-structural variables, transmitted by parental values and personality structures, influence the child’s socio-moral development only indirectly.

In order to test the postulated hierarchical model structure, we must first examine the influence of the socio-structural variables on moral judgment. To ascertain the combined characteristics of the socio-structural variables which most influence the child’s tendency toward an individual judgment style, the joint impact of parental values, attitudes, and personality traits will be examined. If the resulting profile of parental values and attitudes corresponds to Kohn’s results and also to the conditions which Kohlberg, Hoffman, and Piaget have formulated in relation to parents’ behavior, one should also be able to establish the corresponding behavioral pattern of the parents by taking into account the socio-structural conditions in which children have developed one or the other type of judgment. However, this evidence does not confirm the hierarchical model. In order to prove the indirect influence of the socio-structural variables on moral judgment, which can first be regarded as confirmation of the multiple-level model, the influence of the family environment on moral judgment must be judged independently of socio-structural variables. Should covariances appear here, it will be necessary to check whether the covariances between the social structural variables and the moral judgment can be eliminated through partialization of the covariances between the family environment and the moral judgment. If any such covariances can be eliminated this way, the structure of the model is confirmed, or it is demonstrated that the socio-structural conditions which lead to a certain moral judgment type also promote, in both children and parents, the behavior necessary for this judgment type. Thus we shall have proven that these parental behavioral patterns intervene between the socio-structural conditions and the moral judgment.

Testing instruments: (1) Income, professional position, professional training, and education. (2) Bureaucratic vs. non-bureaucratic organization. (3) Extent of control, work complexity, routinization, and intrinsic work orientation. (4) 16 PF Test (Cattell) of both father and mother. (5) Parental values with Kohn’s scales, each from father and mother, each for oneself and for the child. (6) Family size, mother’s employment, constellation of siblings. (7) “Piaget-histories,” Raven’s Progressive Matrices, Vygotski’s Concept Formation Experiment, Flavell’s Role-Taking Task.

Figure 1 Empirical Multiple-Level Model of Reproduction

The following findings are based on an investigation of 176 boys nine to ten years old and their parents, conducted in 1974, The data have been reanalyzed, taking into consideration certain suggestions made by Köckeis-Stangl (1980). Except for minor changes, the findings were not different from those of our former analysis (see Bertram, 1978).

Findings

The Socio-Structural Conditions of Moral Judgment

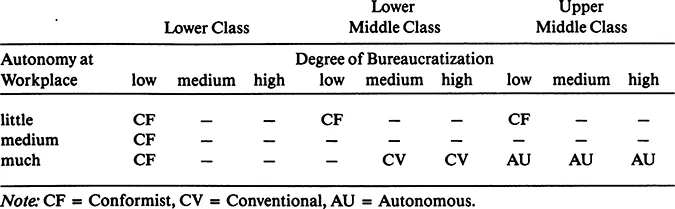

There is no doubt that the types of moral judgment investigated here vary enormously from a socio-structural viewpoint. In Table 1 the judgment types “autonomous,” “conventional,” and “conformist” are represented according to their socio-structural distribution; accordingly, I have restricted myself to naming only the socio-structural conditions which most positively influence each type of judgment. Boys are especially likely to judge autonomously when their parents belong to the upper middle class and possess high autonomy at their place of work. Boys tend to judge conventionally when their fathers belong to the lower middle class and possess high autonomy at work within a medium-sized or large bureaucratic organization. Finally, boys usually judge in a conformist way when their fathers work in less bureaucratic organizations or in small firms, and belong to the lower classes. In such cases, autonomy at the place of work does not play a significant role, whereas in the lower and upper middle class the conformist type of judgment is dominant in small firms or in less bureaucratic organizations if the father has little autonomy at his workplace.

Table 1

Socio-Structural Constellations and Types of Moral Judgment

The socio-structural distribution of the three judgment types as depicted in Table 1 shows clearly that moral judgment does not vary according to class; instead, each judgment type can be assigned to specific constellations of class, workplace conditions, and workplace structure. Only when fathers in the upper middle class experience autonomy at work do their sons show corresponding judgment preference, while fathers of the same class who work in small firms but have little autonomy, influence socialization at home in such a way that the boys are more likely to judge in conformist manner. Moreover, the significance of socio-structural factors for moral judgment also varies. Under reciprocal partialization the class membership, followed by autonomy in the workplace (beta = .18), most influences the type of autonomous-flexible judgment (beta = .27). In comparison, the conformist judgment type is influenced by the father’s membership in a bureaucratic or unbureaucratic organization (beta = .23) and by autonomy in the workplace (beta = .23). In regard to the conventional judgment type, all three socio-structural variables are equally meaningful.

These authentic variations of moral judgment, evoked through workplace conditions and the structure of the working organization, make it clear in the first place that the prevalent, class-specific interpretation of the Reproduction Model for social inequality is inappropriate for explaining the influence of socio-structural variab...