![]() Part One

Part One

The Context of Criminal Investigation![]()

Chapter 1

From trait-based profiling to psychological contributions to apprehension methods

Laurence Alison1

Traditional ‘trait-based’ profiling

Traditionally, profiling has involved the process of predicting the likely socio-demographic characteristics of an offender based on information available at the crime scene. For example, the Crime Classification Manual, a handbook for offender profiling issued by the FBI, explains that, ‘The crime scene is presumed to reflect the murderer’s behavior and personality in much the same way as furnishings reveal the homeowner’s character’ (Douglas et al., 1992: 21). The idea of inferring one set of characteristics from one set of crime-scene actions relies on two major assumptions. Firstly, there is the issue of behavioural consistency: the variance in the crimes of serial offenders must be smaller than the variance occurring in a random comparison of different offenders. Research findings indicate that this appears to be the case for rapists (Bennell, 1998; Grubin et al., 1997). Criminologists, in adopting a ‘molar’ approach, define behavioural consistency as the probability that an individual will repeatedly commit similar types of offences (Farrington, 1997). In contrast, psychologists have emphasized a ‘molecular’ analysis of criminal behaviour, where behavioural consistency is defined as the repetition of particular aspects of behaviour if the same offender engages in the same type of offence again (Canter, 1995). A number of studies have provided support for the notion of offender consistency. For example, Green et al. (1976) studied the consistency of burglary behaviour. Based on 14 behavioural ‘markers’, Green and his colleagues were able to accurately assign 14 out of 15 cases of burglary to the relevant three burglars. Similarly, Craik and Patrick (1994), Wilson et al. (1997), and Grubin et al. (1997) all concluded that behavioural consistency exists in the crime-scene behaviours of serial rapists, though only to a limited degree.

However, the second assumption, referred to as the ‘homology problem’ (Mokros and Alison, 2002), presents a significant hurdle for traditional profiling methods. This assumption relies on the hypothesis that the degree of similarity in the offence behaviour of any two perpetrators from a given category of crime will match the degree of similarity in their characteristics. Thus, the more similar two offenders are, the higher the resemblance in their behavioural style in the offence. The idea that the manner in which an offence is committed corresponds with a particular configuration of background characteristics differs from the more humble findings of bivariate measures of association, such as the findings of Davies et al. (1998) that offenders who display awareness of forensic procedures by destroying or removing semen are four times more likely to have had a previous conviction for a sexual offence than those offenders who do not take such precautions.

Traditional profiling methods make far more ambitious claims than these likelihood predictions. For example, Douglas et al. (1986) all refer to proposed relationships between clusters of background features from crime-scene actions in order to develop a psychological ‘portrait’ of the offender. When these relationships are tested, however, the results are not very promising. In the study by Davies et al. (1998) the integration of a range of crime-scene actions as predictors within logistic regression models failed to show a substantial improvement over the information obtained through simple base rates in the majority of instances. Similarly, in the study by House (1997), the 50 rapists in the sample appeared relatively homogeneous with respect to their criminal histories, regardless of whether they acted in a primarily aggressive, pseudo-intimate, instrumental/criminal or sadistic manner during the sexual assault. Mokros and Alison (2002) examined 100 male stranger rapes, using information on the crime-scene behaviour of 28 dichotomous variables taken directly from a police database. This represented a random sample from a total of more than 500 victim statements stored in the database. They were unable to find any clear links between sets of crime-scene behaviours and sets of background characteristics.

Traditional profiling as naïve trait psychology

Alison et al. (2002) state that the assumptions underlying many profiling methods are similar to assumptions inherent in naïve trait theories of personality. In the naïve trait view primary traits are seen as stable and general in that they determine a person’s inclination to act consistently (stable) in a particular way across a variety of situations (general). As the notion of behavioural dispositions implies, traits are not directly observable but are inferred from behaviour (Mischel, 1999). Traditional trait-based (TTB) profiling tends to attribute behaviours to underlying, relatively context-free dispositional constructs. Thus, both TTB profiling methods and traditional trait theories are nomothetic in that both try to make general predictions about offenders; deterministic in that both make the assumption that all offenders are subject to the same set of processes that affect their behaviour in predictable ways; and finally, both are non-situationist in the belief that behaviour is thought to be consistent in the face of environmental influences.

Based on the evidence concerning the traditional trait approach, one would not expect a task such as offender profiling, in which global traits are derived from specific actions (or vice versa), to be possible. Moreover, the profiler’s task is even more ambitious than this in that inferences are made about characteristics that are not appropriate for a psychological definition of traits (including features such as the offender’s age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, degree of sexual maturity and likely reaction to police questioning (Annon, 1995; Ault and Reese, 1980; Grubin, 1995; Homant and Kennedy, 1998).

There are of course many studies of sexual offenders that support an aggregate level of research on traits. For example, Proulx et al. (1994) demonstrated that rapists display significantly diverse facets of personality disorder depending on their level of physical violence as demonstrated in their crime-scene behaviour. Among their findings was the observation that more violent offenders score significantly higher on the histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial and paranoid sub-scales than the less violent offenders. Langevin et al. (1985) report similar results for another sample of rapists.

Proulx et al. (1999) identified a sample of rapists according to their respective modus operandi into three groups: sadistic, opportunistic and anger rapists. They found substantial differences between the sadistic and the opportunistic types with respect to personality disorders. The sadistic offenders were more likely to have avoidant, schizoid and dependent tendencies, whereas the opportunistic offenders were characterized as narcissistic, paranoid and antisocial.

The study by Proulx et al. (1999) indicates that it may be possible to discriminate between rapists based on their crime-scene actions and that such differentiation may be reflected in personality. Such a procedure could properly be referred to as a psychological profile, since it refers exclusively to particular psychological constructs. In contrast, the traditionalists’ use of the term ‘psychological profiling’ relies on the generation of demographic characteristics of offenders and is, therefore, something of a misnomer.

Thus, the evidence for a nomothetic, deterministic and non-situationist model of TTB offender profiling is not compelling. Despite this and despite the admission by many profilers that their work is little more than educated guesswork, the utility of profiling seems to be generally accepted as valid. For example, Witkin (1996) reported that the FBI had 12 full-time profilers who, collectively, were involved in about 1,000 cases per year.

Interpretation of the advice

Beyond the issue of the feasibility of the process lie potential problems associated with the interpretation of the reports. To date, there has been little systematic research of such reports, and few suggestions as to how such advice might be deconstructed and evaluated. One exception is a small-scale study recently conducted on a sample of European and American offender profiles from the last decade (Alison et al., 2003a). Alison et al. established that nearly half of the opinions expressed within these reports contained advice that could not be verified post-conviction (e.g. ‘the offender has a rich fantasy life’), while over a fifth were vague or open to interpretation (e.g. ‘the offender has poor social skills’). In addition, in over 80 per cent, the profiler failed to provide any justification for the advice proposed (i.e. they did not clarify what their opinion was based on).

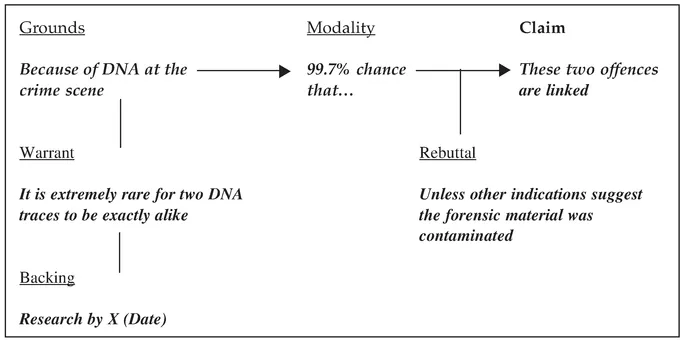

The coding framework developed to evaluate profiles was based on Toulmin’s work in the 1950s. Toulmin’s work (1958), originally based on the analysis of philosophical and legal rhetoric, proposed that arguments could be broken down into various component parts to enable researchers to scrutinize the strengths and weaknesses of various aspects of any given claim. He suggested that arguments contain six interrelated components: (1) the claim, (2) the strength of the claim, (3) the grounds supporting the claim, (4) the warrant, (5) the backing, and (6) the rebuttal. Figure 1.1 illustrates how this format can be applied to the investigative domain with reference to the linking of offences. The claim, in this example, involves the statement that two offences are linked. In order to substantiate this claim certain components must be present. The first involves the strength, or modality of the claim. This may come in modal terms such as, ‘probably’, ‘possibly’, ‘certainly’, but in our hypothetical case this is presented as a statistical probability (i.e. ‘a 99.7 per cent chance that ...’). The modality component indicates the extent to which we should rely on the claim being

Figure 1.1 Toulmin’s structure of argument using a hypothetical ‘DNA’ example

true, in this case the analyst is suggesting we take the claims very seriously. The grounds are the support for the claim. In this case, the reasoning relates to the presence of a DNA trace at the crime scene. The warrant authorizes the grounds because ‘it is rare for two DNA traces to be exactly alike’. The backing, or formal support for the warrant, comes in the form of a citation to a specific example(s) of research. Finally, the rebuttal allows us to consider the conditions under which the claim ceases to be likely. Thus, if further evidence becomes known (for example, contamination), the claim may have to be adjusted accordingly.

There are several reasons why Toulmin’s philosophy of argument is a useful method of exploring the construction of reports. Firstly, there are few clear bases upon which such advice is given. There exist few formal models of how profiling works, why it works or, indeed, if it works. Thus a framework, in which we can evaluate the justification for any given claim, allows us to identify weaknesses in those claims. It allows us to establish the certainty of the claim (modality), the conditions where the claim must be re-evaluated (rebuttal), the grounds upon which the claim is made and the warrant and backing for those grounds. In this way investigators can measure the weight and significance that can be attached to any inference or conclusion. Secondly, there is increasing pressure on investigating officers and profilers to carefully consider the potential legal ramifications of employing such advice in their inquiries (Ormerod, 1999). Profilers must approach each report with strict standards of evidentiary reliability and relevancy afforded to court procedures. Finally, by applying this framework to their own reports, profilers may gain insight into the processes that they themselves engage in when preparing material for the police.

The danger of not making the justifications of such statements clear (especially in the case of ambiguous statements) includes the potential increase in erroneous interpretation of the material. Alison et al. (2003b) have argued that the lack of clarity in such reports could lead to problems with the interpretation of the material in similar ways in which so-called ‘Barnum effects’ operate in social psychology. For example, it has long been established that people tend to accept vague and ambiguous personality descriptions as uniquely applicable to themselves without realizing that the same description could be applied to just about anyone (Forer, 1949). This has been given the name ‘Forer’ or ‘Barnum’ effect in deference to P. T. Barnum’s claim that his circus included ‘a little something for everyone’ (Meehl, 1956). It is possible then that a contributory factor in the perception of usefulness, despite outcome measures, can be explained by the readiness to selectively fit ambiguous, unverifiable information from the profile to the offender. Therefore, after a suspect is apprehended, or if the investigating officer has a ‘type’ of offender in mind, it is possible that the enquiry team engage in an inferential process ‘invited’ by the ambiguity of the profile. As Hyman states in reference to readings from psychics, ‘once the client is actively engaged in trying to make sense of the series of sometimes contradictory statements issuing from the rea...