- 796 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Public Sector Economics

About this book

The Handbook of Public Sector Economics builds an understanding of the role of public economics in public administration, public policy, and decision making. The handbook introduces a wide variety of current issues related to the public provision and production of goods and services.

The volume documents the history of economics and fiscal doctrine, explores the theory of public goods and the structures from which resources are collected and expanded, and analyzes heavily debated issues of economics that are important to current and future practitioners of public policy and administration. It focuses on the effects of fiscal policy on savings and investment, consumer behavior, labor supply, wealth, property, and trade. Written in a simple and straightforward style, the initial chapters establish the foundation of public economics, with the subsequent chapters addressing the collection and distribution of government resources and market reactions to fiscal policies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Public Sector Economics by Donijo Robbins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction to Public

Economics and

Fiscal Doctrine

Economics and

Fiscal Doctrine

1

The Evolution of Economics:

The Search for a Theory of Value

The Search for a Theory of Value

That evening there was a huge dinner of captains of industry, bankers, and professors. Keynes sat next to Max Planck, the German physicist and Nobel prize winner. Planck told him that he had thought of studying economics early in his life but had found it too difficult….What Planck meant was that economics was imprecise and intuitive, and therefore “overwhelmingly difficult” for those whose gift was to imagine, and pursue the implications of known facts.—Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: The Economist as Savior, p. 119.

1.1 Introduction

The above story about John Maynard Keynes’ encounter with Max Planck has been told so often one wonders whether it is apocryphal. Keynes’ biographer, however, confirms that Keynes did in fact tell this story in his obituary of another great economist, his mentor, Alfred Marshall. It is interesting to begin with this tale because many economists have, in fact, tried to steer economics to emulate the natural sciences, particularly physics. Planck’s statement, while a compliment in emphasizing the difficulties in analyzing and understanding the complexities of economic systems, would be discouraging for those who have sought throughout the history of the field to give it the same precision as is found in physics (Mirowski, 1989). The subtitle of this chapter, “The Search for a Theory of Value,” underlines the efforts spent by economists to find universal laws underlying the working of the economy that would have the same power as a theory of gravity or the second law of thermodynamics, or the conservation principle, ideas that have been important in the history of physics.

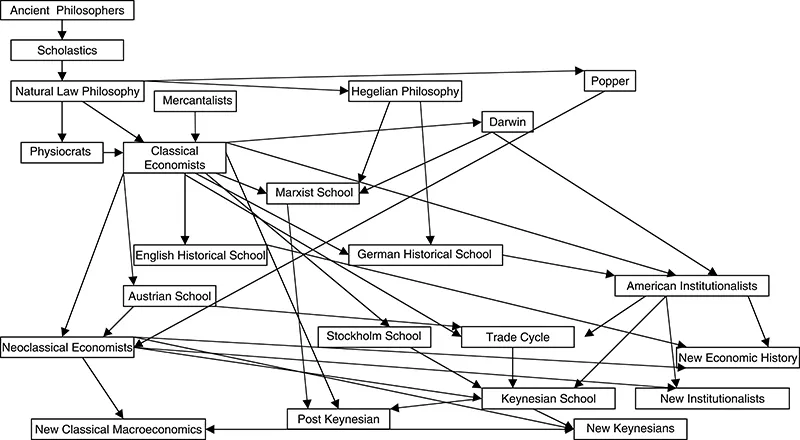

The search for a theory of value, therefore, becomes a useful organizing tool to discuss the evolution of economics (see Figure 1.1). While not all economists spend as much time thinking about whether economics has a good theory of value, some of the important turning points in the history of the field have centered on finding or improving on one. And some feel that the field is ultimately about value (e.g., Schumpeter, 1966; Stigler, 1965): what people value, the valuation process, impediments to the valuation process, and what value actually means. It is a concern that begins with the earliest philosophers to discover the intrinsic source of value, over and above the price something may fetch in the marketplace, but received its first truly thorough treatment with the classical economists, starting in the eighteenth century.

Before beginning, an apology is in order, however. This chapter is a layperson’s guide to the history of thought. A detailed critique of various doctrines is beyond the scope of this already long piece. The focus is on the evolution of economic thought and critical turning points in the history of that thought. Much is left out. For a detailed critique, the reader is referred to Schumpeter (1966), with 1100 pages of analysis, and Blaug (2002), with 700 pages.

Figure 1.1 Evolution of economics.

1.2 The Classical Economists

1.2.1 Precursors

Before getting to the eighteenth century, many historians of economic thought begin with the earliest discussions of economics, usually going back to the fourth century B.C. to the time of Aristotle. One should note, however, that Huag-Chang (1974) traces economic thought even further back to the writings of Confucius in the sixth century B.C. in China, and Sen (2002) notes an Indian philosopher, Kautilya, who was primarily responsible for writing Arthasastra, a book devoted to economics and politics, around the same time that Aristotle was speculating about economic topics interspersed with his writings on politics and ethic. So the current discussion focuses on the Western tradition in economic thought as it has evolved over time; which, after all, is the tradition that influenced the classical scholars of the eighteenth century.

The word economics comes from the Greek word, oikonomia, which was a discipline that focused on estate management and public administration (Lowry, 1979). And generally when Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) used this term, he was referring to household management.* Nevertheless, he discussed a number of topics relevant to current economic thought (Spiegel, 1991). He was the first to discuss the difference between value in use and value in exchange, which has been an important consideration in the development of theories of value in modern economics. He was one of the first to give a defense of private property, using an argument familiar to many economists, that private property provides an incentive for owners to use their land more productively. This was also an argument adopted by the Greek Stoics, a philosophical school of thought that emerged towards the end of Aristotle’s life. The Stoics made contributions to the field of logic, and they embraced reason and the concept of natural law. Stoicism was introduced to the Romans around 200 B.C. and had a profound influence on Roman jurisprudence.

* It is important to remember that in ancient Greece most people lived on self-sufficient farms. A separate economic sphere was unheard of for most people. So since most economic decisions involved household management, this was not a trivial topic.

Nevertheless, like many of that time, Aristotle was opposed to interest, which he felt led to unnatural accumulation (Ekelund and Herbert, 1975). And while he felt commerce was necessary, he was suspicious of it; as the Greeks — placing social cohesion above the benefits that might come from trade — felt that the specialization that would result could undermine the common purpose (Polanyi, 2001; Muller, 2002).

Schumpeter (1966) was dismissive of Aristotle’s contribution to economics, for while he condemned interest (because of his social concerns), he never tried to analyze why people are willing to charge and pay for interest — the “why” questions that are of importance to economists. Lowry (1979) disagrees, noting the G.L.S. Shackle (1972) definition of economics as a field that reduces incommensurables to common terms, which is something Aristotle did, in fact, do.

Spiegel (1991) notes that the less philosophical Romans contributed significantly less to economic thought, unless one takes into account the importance of Roman law — especially that dealing with contracts and property — that served as a framework for British common law, which supported the emergence of capitalism. Roman jurists adopted from the Stoics the concept of natural law — of great importance to classical political economists — which was “interpreted to embody the all-pervasive reason that governs the world and to reflect the nature of things” (Spiegel, 1991, p. 36). Schumpeter (1966) also gives credit to Roman jurists in contributing to economic thought, albeit in regards to practical purposes, because they often did ask the right kinds of questions — the “why” questions.

Schumpeter (1966) also credited many of the Scholastics for asking the right questions. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, discussions of economic issues fell into the hands of priest-scholars, who attempted to carry on the legacy of Aristotle. Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) is particularly given credit for trying to reconcile Catholic philosophy with Aristotelian thought. He was a defender of private property, defended the businessman, and held profit as morally neutral. He defined the concept of a “just price” in terms of the prevailing market price, and opened the door to reconsidering prohibitions against usury (Muller, 2002; Schumpeter, 1950; Screp-anti and Zamagni, 2001; Spiegel, 1991). Although he defended commerce, Aquinas expressed concerns about people making money for its own sake or to improve their places in the social order (Muller, 2002). Aquinas and the other scholastics were also concerned with the concept of natural law and provided some inklings of a subjective (utility) theory of value (Schumpeter, 1966; Robbins, 1948).

With the demise of feudalism and the emergence of mercantilism in the sixteenth century, one sees an explosion of writing on economic issues, which can be found in hundreds of pamphlets that were written and distributed, thanks to advances in the printing press.* This was a time when the focus was on the consolidation of the nation state; with a mercantilist philosophy that advocated active government intervention to promote the trading dominance of the nation and the accumulation of gold and other forms of wealth in the interest of the state. Intellectuals were more willing to advocate the pursuit of wealth for its own sake and the idea that only through love of one’s self could one benefit others — i.e., that self-interest leads to trade that benefits all of society (Muller, 2002). Because these were radical ideas for the time, many of the pamphlets written on these topics were anonymous (Letwin, 1964). Although most of these pamphlets were focused on practical matters — such as the money supply and usury laws — some of the discussions opened by the mercantilists are with us today, especially in terms of the role and importance of money (gold) in stimulating the economy.

* Schumpeter notes that most of this writing was not in English. Commentators from Italy, Spain, France and England contributed to this literature.

Eklund and Hebert (1975) note that the mercantilist writers were very concerned that their writings sound “scientific,” rather than merely self-serving. The most successful, according to Letwin (1964), was Dudley North (1641–1691), who produced the first equilibrium model (although rudimentary) with respect to the money supply and was one of the first to suggest that the interest rate is a price for the use of money, an idea later used by Keynes.

By the seventeenth century, philosophers such as Voltaire (1694–1778), who came to be a wealthy man in his own right, were openly advocating the pursuit of the wealth through the market (Muller, 2002). The early seventeenth century was also the time when the term political economy was used in a book title for the first time: Traité de l’économie politique by a French manufacturer named Montchrétien. While the book is not highly regarded, it is important to note that the author used the term political economy to distinguish it from the household economics that was of concern to the ancient philosophers (Screpanti and Zamagni, 2001). Most importantly, the seventeenth century was a time of the emergence of rationalist philosophers such as Descartes and John Locke, who were optimistic in their belief in the power of reason. This optimism was enhanced by discoveries in science, particularly those of Newton, whose work presented the possibility of a knowable universe.

Locke (1632–1704) is particularly important to the history of economic thought. He developed the idea of private property as a natural right and gave a reasonable description of what economists call the quantity theory of money, which suggests that large injections of money into the economy will generally result in higher prices rather than greater output and wealth. This was an idea that ran counter to that of many mercantilists, who often felt that the state could not accumulate too much gold. It remains one of the first modern economic arguments made about the causes of inflation and includes a clear understanding of the velocity of money (Schumpeter, 1966). Locke also discussed the “natural” rate of interest, thus incorporating a natural law concept into the discussion of economics. Further, his deductive method was adopted by the classical economists and remains a cornerstone of modern economics (Letwin, 1964). Locke also suggested the possibility of a labor theory of value but did not really use it.

Locke was not the only philosopher to make a contribution. Letwin (1964) points out that most British philosophers writing between 1660 and 1850 focused on economic issues — Locke, Berkeley, Hume, Bentham, and John Stuart Mill — an indication of the extreme importance of economic theory to the times. Some were skeptics, however. One was Edmund Burke (1729–1797), who is famous for saying, in response to the French Revolution, that the “age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators has succeeded, and the glory of Europe is extinguished for ever” (Muller, 2002, p. 132). Burke was concerned that rationalism was undermining those social institutions that were necessary for the preservation of social order, a concern that is also expressed by Hegel some years later.

1.2.2 From Petty to Hume

William Petty (1623–1687) was a physician and a contemporary of John Locke. He is often cited as the first of the classical economists for two reasons. Letwin (1964) described his economic treatises — Treatise on Taxes and Political Arithmetik — as the first truly scientific works in economic theory, citing the internal unity and economy of his analyses, the absence of ad hoc explanations, and his use of basic data to highlight his key points. For Marx in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), Petty stood out for his search for “natural value,” recognizing labor as the key source of value, with land playing a smaller role in contributing to value. He acknowledged the importance of the division of labor (anticipating Smith) and had at least some sense of economic surplus (Niehans, 1990; Screpanti and Zamagni, 2001). In the course of his work, Petty derived the concept of National Income, which would become of great importance to modern macroeconomics, and demonstrated an understanding of the possible impact of population growth, long before Malthus. He also introduced many terms to the lexicon of economics; for example, as far is known, he was the first to adopt the term ceteris paribus — all things remaining equal — which is liberally sprinkled throughout economic writing up to the present (Spiegel, 1991). Use of the term suggests scientific inquiry, where one is trying to understand the impact of one variable while holding constant the impact of other possible variables.

Richard Cantillon (1680–1734), a French businessman, is also of interest in having a value theory based on land and labor — but giving more weight to land than...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Part I Introduction to Public Economics and Fiscal Doctrine

- 1 The Evolution of Economics

- 2 Basic Economics of Fiscal Decentralization

- 3 Voting and Representative Democracy

- 4 Bureaucracy and Bureaucrats

- Part II Theory of Public Goods

- 5 Public Goods

- 6 Provision and Production of Public Goods

- Part III Collection, Allocation, and Distribution of Resources

- 7 Tax Systems and Structures

- 8 Fiscal Characteristics of Public Expenditures

- 9 Intergovernmental Grants

- 10 Public Debt and Stability

- 11 Transportation Infrastructure

- 12 E-Government Expenditures

- Part IV Market Reactions Collection, Allocation, and Distribution

- 13 Government Fiscal Policy Impacts

- 14 Taxation and Consumer Behavior

- 15 Federal Taxes and Decision Making

- 16 Wealth, Property, and Asset-Building Policy in the U.S.

- 17 International Trade and Public Policy

- Index