- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Illustrated History of Surgery

About this book

Throughout its development, from an ancient craft of magic and religion to a field of science and technology, surgery has inspired strong feelings--hope and admiration, fear and censure, but never indifference. Here, for the first time-- in The Illustrated History of Surgery--is a readable and chronological account, across the whole spectrum of world history, of the development of surgery and of the great personalities whose skill and courage paved the way for the modern surgeon. The book also includes information on the use of drugs, herbal remedies, early anaesthetics and a whole range of procedures related to surgery and its evolution. The text ranges from primitive surgery in prehistoric times to today's transplants and implants - with a glimpse into how modern surgery is likely to develop in the future. There are portraits of the great surgeons throughout the ages, detailed accounts of the milestones in the progress of the profession - the breaking of new ground and forming of solid bases from which the next generation of surgeons could advance to new and revolutionary techniques. The Illustrated History of Surgery is a beautifully presented book, with more than 200 colour illustrations gathered from around the world; it tells the story of surgery in a way that is both intelligible and enthralling.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Illustrated History of Surgery by Sir Roy Calne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

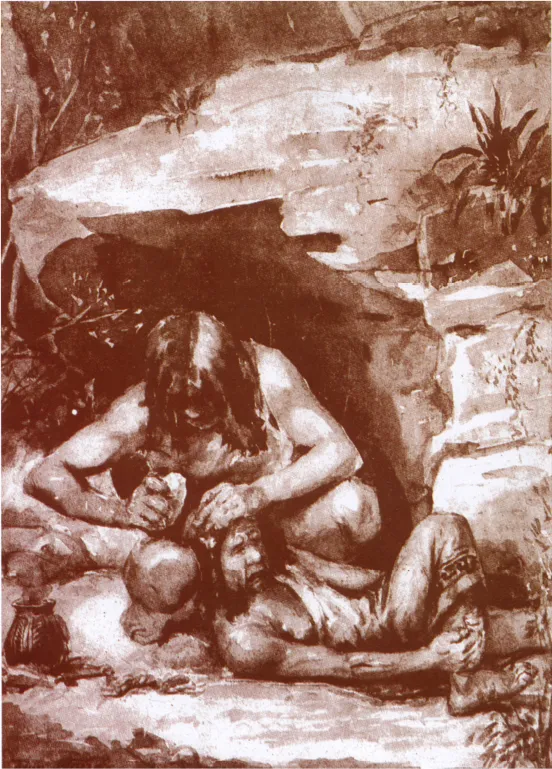

MEDICAL practice in many parts of the world has very old traditions: this operation, resembling Stone Age trepanations, was depicted in the highlands of Peru as late as 1923. The medicineman, or shaman, treated a melancholic woman by placing hot oil in a cut on her scalp. He chewed coca leaves and used the juice to anaesthetize the wound.

CHAPTER

1

1

The beginnings of medicine

Surgery is an art of working with the hands. Its name derives from the Latin word chirurgia, which in turn comes from the Greek cheiros (hand) and ergon (work). As a branch of medicine, surgery deals with injuries, deformations and unhealthy physical changes of kinds that require manual treatment, with or without instruments. A well-known description of its concerns was recorded by the sixteenth-century French surgeon Ambroise Paré:

“There are five duties in surgery: to remove what is superfluous, to restore what has been dislocated, to separate what has grown together, to reunite what has been divided and to redress the defects of nature.”

Prehistoric and primitive healing

Surgery is as old as mankind. Its age can thus be reckoned to around half a million years, from the time when Java Man, Pithecanthropus erectus, evolved on earth. Bone tumours have been identified in Java Man. This condition, probably along with several others, is in fact older than human beings. It has been found in dinosaurs, which lived some 150 million years ago.

We may assume that the earliest surgery was devoted to tending wounds. Archaeology can tell us little about how it was practised during prehistoric times. However, it is likely to have been done in more or less the same way as among primitive folk today. A common trait of most primitive tribes is the instinct to cover wounds with leaves and other parts of plants. Filling them with spider-webs is a further popular method of treatment. In many places, the belief that spider-webs help to stop bleeding arose very early and continued for a long time. Shakespeare refers to this in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Act III/1):

“I shall desire you of more acquaintance, Good Master Cobweb:

If I cut my finger I shall make bold with you…”

Indeed, little boxes containing spider-webs belonged to every soldier’s field-equipment at the Battle of Crécy in 1346!

Primitive peoples know of other blood-stanching methods as well. The North American Indians once had a special powder which was prepared from certain herbs. Various peoples have also understood how to use heat for stanching. Their procedures are numerous—hot stones, the glowing-red needles and shells of Indians and, of course, the simplest of all, direct burning with a torch or firewood. From these, more sophisticated techniques were developed. Centuries ago, Tibetan monks poured a mixture of sulphur and saltpetre onto wounds, and set it alight. Such a precedent for blood-stanching with amputations survived well into the eighteenth century, when gunpowder was set off on stumps (see Chapter 8).

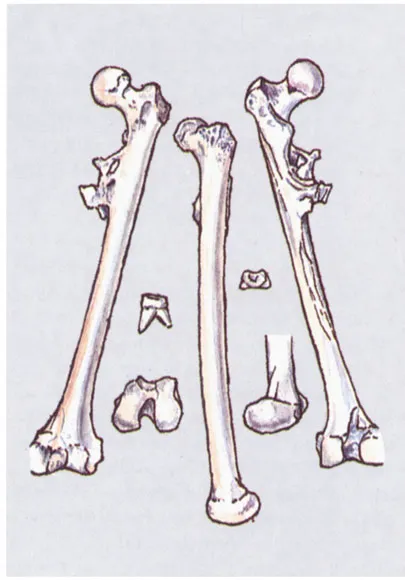

ONE of the oldest known human diseases is tumour growth on bones (exostosis), as in Java Man at least 500,000 years ago. His thigh-bone, found in 1891 by a Dutch doctor, was illustrated in this view from three sides.

Wounds have not only been bandaged with fresh leaves. The ancient Egyptians recommended raw meat, while eaglet-down and sand were used in America, and animal excrement has been laid directly on wounds for centuries throughout the world. The latter, to be sure, is hardly a safe method, since tetanus bacilli thrive in fresh excrement. But it is far from certain that tetanus existed in prehistoric times. Bacteria may undergo peculiar mutations and alter their disease-causing properties.

Nor is there any reason to doubt that our distant ancestors realized the value of draining a wound. The need to create an outlet where pus has collected is an old rule. How this can be done with primitive means is shown by the Dakota Indians. They sharpened a feather-quill and mounted it on an animal's bladder. The quill was stuck into the afflicted area, and the pus was sucked up into the bladder. The Indians did not stop at that: they left some hollow quills in the wound, allowing a free outlet for fluid and pus. The same principle is still followed today, the difference being that we use rubber tubes.

Early man was also aware of the benefit of closing large wounds. Here, too, we must depend on the evidence of primitive folk, although bone needles of the Old Stone Age have been discovered which could have been used for wound sutures. The Masai tribes in Africa exhibit a clever technique. At a secure distance from each edge of the wound, they employ a sharp awl to make a path for a long acacia thorn; it is then stuck through both edges, and its ends are united with a thread of twined plant fibres. Yet the prize for inventiveness must be awarded to tribes in India and South America, where the surgeon sewed a wound by bringing its edges together while his assistant allowed a termite or beetle to bite across them. When the insect had taken a good bite, its neck was twisted quickly. The jaws, stiffened in death, made a perfect wound-clamp! This principle continues with the agraffe which, however, is fortunately manufactured nowadays of stainless steel or silver.

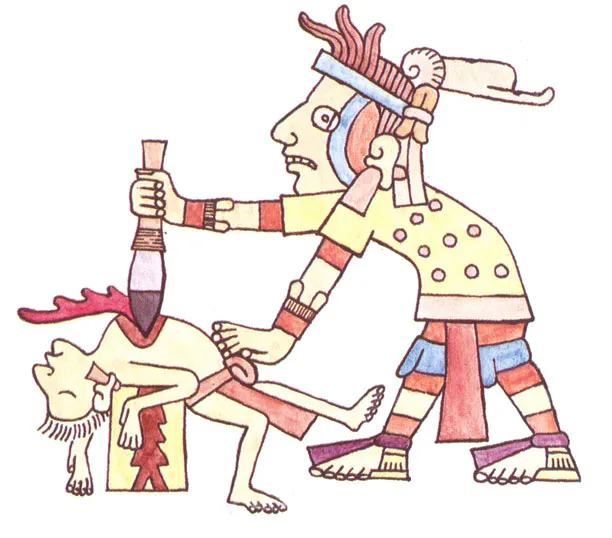

Medicine was highly developed among the Aztecs of Mexico. As early as five hundred years ago, they treated superficial contusions and haemorrhoids with a wound salve which was not unlike modern ones. They were also adept in the use of herbs, and we know that they exploited pain-killing drugs as well as a kind of crude narcotic. Most remarkable, from a surgical viewpoint, is the following advice for treatment of a broken bone:

“First the broken bone should be splinted, extended, and fitted together…and if this is not effective, an incision should be made, the bone ends exposed, and a branch of fir-wood inserted in the marrow cavity…”

This method, now called marrow-pinning, was not rediscovered until the twentieth century!

Bone fractures must have been among the commonest problem of Stone Age folk. Hunting and fishing tribes on the move are slowed down by invalids who cannot keep the pace or, perhaps, travel at all. Bones have been found with healed fractures which indicate that some kind of splinting was used. Setting a broken bone to immobilize it is fairly obvious, since the victim otherwise feels pain.

Simple splints have often been made from suitable tree-branches, but there have been triumphant innovations even in this area. The American Indians were experts at binding broken bones with long strips of bark. Other peoples used soft clay, which dried like a sheath around the injured member – a forerunner to plaster casts. While Stone Age man had little idea of how to relocate a broken bone in its normal position, the results of extremity surgery were by no means poor. The scientist Karl Jaeger has investigated bone remains that were broken during life, and found that the healing was satisfactory in more than half of the cases. This record was surpassed only at the beginning of the last century.

It is not impossible that ingenious prehistoric physicians learned adequate manipulations for curing dislocations and sprains. Many such conditions are treated manually even by modern surgeons, sometimes without any anaesthesia. A good example is “Kocher’s manoeuvre”, which is applied when the upper armbone has moved out of its joint on the shoulder-blade. Hippocrates’ method of reducing a dislocated shoulder is to put the surgeon’s foot gently in the axilla and apply traction on the arm, until the head of the humerus slips back into the glenoid fossa. But primitive folk have used orthopaedic manipulation techniques for much more serious conditions. The English priest William Ellis, who voyaged among the South Sea islands in the early nineteenth century, told of a young man who suddenly contracted acute back pain by carrying a heavy stone. He was laid face-down on the grass, and one comrade pulled upward on his shoulders while another pulled hard on his legs. A leader of the team sat on the patient’s back and pressed with every ounce of weight on the spot where the injury seemed to be. Apparently the operation succeeded, as the young man returned to work after just a few hours—with what we may suppose was a dampened enthusiasm for lifting the heaviest stones.

THE Aztecs inherited much learning from older native cultures, but they had to fight many diseases and wars in the environment of central Mexico. On the one hand, their obsidian knives were as sharp as a modern scalpel, and were used without hesitation. They made such a virtue of cleanliness that their superficial operations were probably more successful than those in Europe until our century. On the other hand, Aztec thinking was dominated by abstract religion and placed little value on human life, or on the profession of healing. It was believed that the gods had to be kept alive by continual offerings of blood and hearts from sacrificed people, as illustrated here.

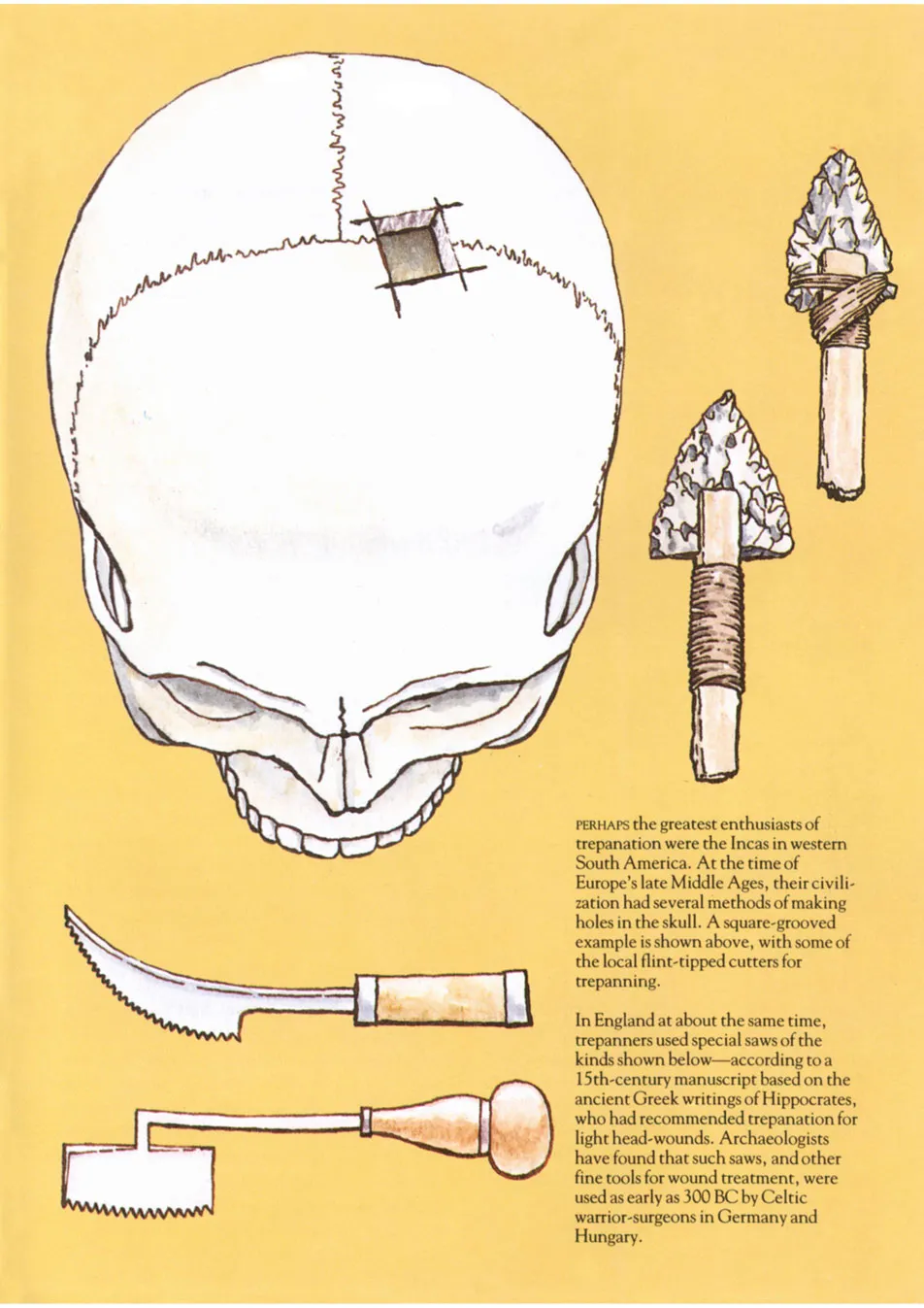

Trepanation

Among the medical feats of our ancestors, the most remarkable is trepanation, or skull-boring. Skulls with holes bored in them have been found by archaeologists from as far back as 4900 BC. The oldest of these occur in the Alsace region. Hundreds of skulls with traces of trepanation are known all over Europe—in Denmark, Sweden, Poland, France, Spain, and the British Isles. A Swedish physician, Professor Folke Henschen, reports that Soviet archaeologists, along the Dnieper River in the 1960s, found crania with oval left-side trepanation holes of 16–18 mm (0.6–0.7 in) diameter. These were thought to date from the Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age. If so, we must raise the age of this practice to some 12,000 years.

The amazing thing about such crania is that evidence exists for the patients’ having survived the operation. Holes in bone are healed by new formation of bone tissue, and the sharp edges of bored or hacked holes become rounded off by so-called callus tissue. This proof of healing is more the rule than the exception. In one study of skull material from the Yantyo tribe in Peru, a researcher found callus tissue in 250 out of 400 crania. Verifications in Europe are fewer, but even here it has been confirmed that most of the patients survived. Further proof of this—and reason for believing in the method—is the discovery of skulls which were trepanned more than once. The record seems to be held by an Inca at Cuzco with seven bore-holes, at least some of which were made on separate occasions.

Nowadays, trepanation is performed to relieve acute pressure on the brain. The usual cause is internal bleeding after a blow on the head. In this case, the operation has a rational justification. The Stone Age finds, and customs of primitive peoples, indicate that our ancestors also used trepanation for such injuries. However, the great majority of skulls show that the operation was done on an intact cranium with no previous signs of violence. Here it must have been intended to relieve an apparent excess of pressure, which is easy to imagine in the event of, for example, migraine or sudden headaches of other kinds.

Magic has obviously played a role as well. The belief that an evil spirit lives in the head and must be let out is very old. But the possibility of repeatedly letting out such spirits has, so far as we know, never existed. Werner von Heidenstam’s fine description of a Stone Age leader in The Swedes and their Chieftains (1908) must, sadly, be ascribed to fantasy:

“On their bare heads, a small lid was attached over a round hole, which had been bored right in the crown-bone. Such a hole was held in great reverence, and belonged only to the most eminent. Through it, evil vapours were able to escape, and the sunlight could enter to absorb their spirits after death.”

There were at least four different methods of trepanning. The crudest was simply to scrape a hole in the skull-cap by means of a piece of flint or a polished mussel-shell. A second method was to make a circular cut in the bone with a flint or obsidian knife, and to deepen it until the hard brain-membrane was reached. Alternatively, and doubtless worse for the patient, a hammer and chisel were used to cut four grooves in a rectangle, then lift out the square piece at their centre.

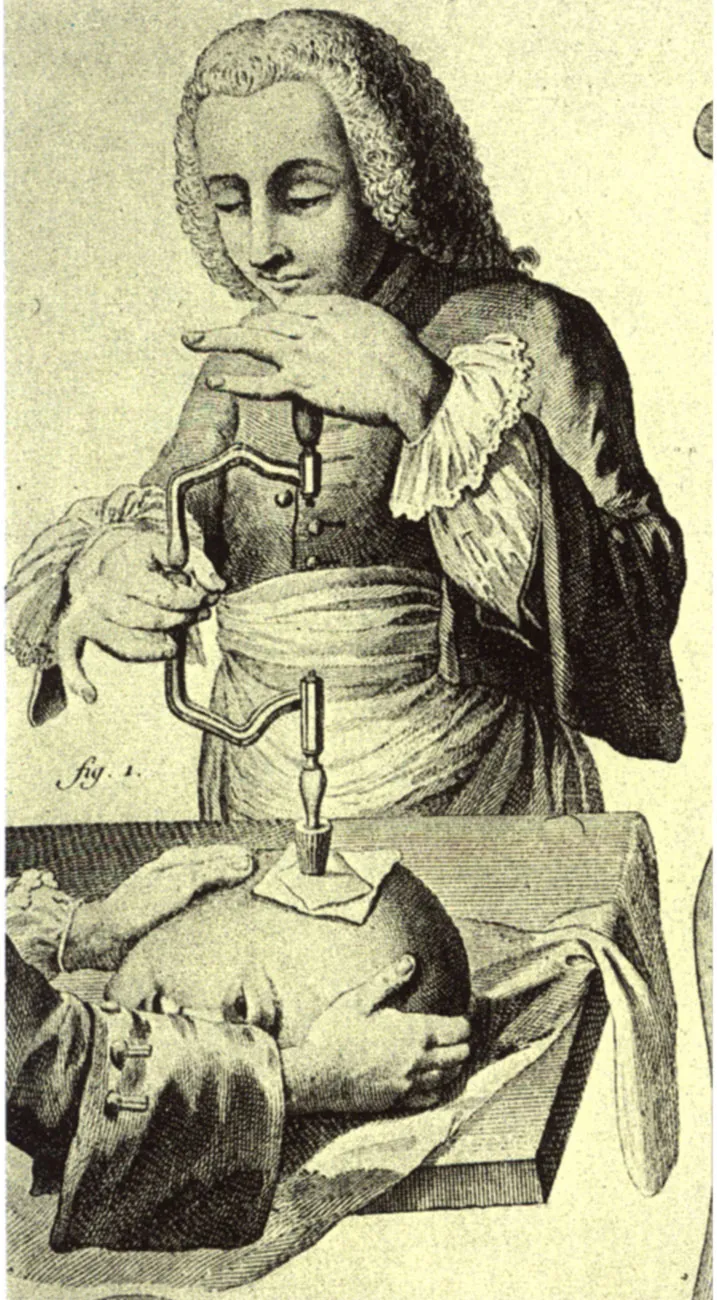

INSTRUMENTS for trepanation were perfected even during the Enlightenment, as illustrated by Denis Diderot’s famous scientific Encyclopédie (1772).

Most elegant, though, was the procedure which gave this operation its name. With a drill-bore, called trypanon in Greek, a wreath of tiny holes was made. These could be united easily with a chisel or knife. Such an operation took little time even with primitive tools. An adept French surgeon named J. Lucas-Championnière (1843–1913), experimenting with instruments of flint, needed only 35 minutes to complete the operation. During the nineteenth century, a scientist travelling in the South Pacific saw a medicine-man do it in half an hour. His patient woke up after several days of unconsciousness and regained perfect health!

Trepanation in Sweden, 1761

The greatest Swedish surgeon of the eighteenth century was Olof af Acrel, chief physician at the Seraphim Hospital. He described the purpose of trepanation as follows:

“Trepanation of the skull is intended to release what has forced its way out of the blood-vessels, or to lift up and remove what, having been forced in, causes meningitis (irritation of the brdn-membrane)—or to both of these ends together.”

The medicine-men or shamans who dealt with trepanations stood high in society. They could also earn a fortune from the practice. Not only may we assume that they were well rewarded by every cured patient and his family. In addition, they conducted a lively trade with the pieces of bone which they extracted from people’s skulls. Such amulets were greatly prized for magical protection from illness and accidents. Researchers have even wondered whether the demand for skull-bone contributed to the prescription of trepanations. There are actual records of amulets measuring about 8–9 cm (3.1–3.5 in). No medical reason can exist for making such enormous holes, and it is very unlikely that the patients survived the serious risk of infection with meningitis.

The first anaesthetics

Our ancestors probably had a greater tolerance of pain than we do. Yet they naturally looked for ways of stopping pain, both in treating illness and as an anaesthetic in operations. Perhaps the earliest pain-killer was alcohol, which was discovered long ago and is produced by nearly all peoples in one form or another. Nor is there a lack of descriptions as to how trepanations began, in many...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Editor’s foreword

- Preface

- 1 The beginnings of medicine

- 2 The rise of Western surgery

- 3 Medieval medicine

- 4 Surgery in the Renaissance

- 5 Medicine becomes a science

- 6 The surgeons of the Enlightenment

- 7 Surgery in the Age of Revolutions

- 8 The human face of surgery

- 9 The triumph of complex operations

- 10 The world of modern surgery

- Chronological Table

- Bibliography

- Illustration Sources

- Index