- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Parliaments in Contemporary Western Europe

About this book

The relationship between parliament and government is fundamental to a political system. In this volume, a distinguished team of specialists explore that relationship and consider to what extent parliaments have the capacity to constrain governments. Are there particular institutional features, such as specialisation through committees, that enhance their capacity to influence public policy?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Parliaments in Contemporary Western Europe by Philip Norton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction:

The Institution of Parliaments

PHILIP NORTON

THE relationship of parliament to government is fundamental to each political system. The growth of governments in the twentieth century has marginalised parliaments as bodies regularly engaged in policy making yet, at the same time, has emphasised their significance in fulfilling a number of other tasks in the political system.

A parliamentary form of government is the norm in western Europe. Governments derive their legitimacy from parliamentary elections. That legitimacy is reinforced by the activity of parliaments in between elections. Parliaments provide the means by which the measures and actions of government are debated and scrutinised on behalf of citizens, and through which the concerns of citizens — as individuals or organised in groups —may be voiced. The extent to which they carry out such actions, and are seen by citizens to carry out such actions, may be argued to constitute an essential underpinning of the legitimacy of the political system in the eyes of electors. What Robert Packenham has termed the function of latent legitimation of a legislature may thus be characterised as a dependent rather than an independent variable, deriving from the extent to which the legislature effectively fulfils these other tasks.1

These various tasks entail a number of relationships. There are relationships with actors other than government. There is a relationship between the parliament and citizens as citizens. There is a relationship between the parliament and organised interests, including companies, civic bodies, sectional interest groups and promotional groups. There is a relationship between parliament and the courts, inasmuch as the courts may have the power to rule on the constitutionality of measures passed by parliament and to interpret the laws passed by parliament. There is also a relationship with government. It is this relationship which forms the basis of this particular study. This relationship, though, is not discrete. Parliament may constitute an important conduit for the transmission of the views and demands of citizens and particular interests to government. It undertakes various tasks on behalf of those who are outside its walls.

Knowledge of that wider context informs our study but is not the focus of it. That is for other volumes in this series.2 Our focus here is the work done by parliaments on behalf of that wider community. That focus prompts a number of questions. What is the current relationship between parliaments and governments in western Europe? What are the mechanisms available to parliaments to scrutinise and influence the actions of government and the measures of public policy proposed by government? What use is made of those mechanisms, and with what effect? And has their use and effectiveness changed in recent years?

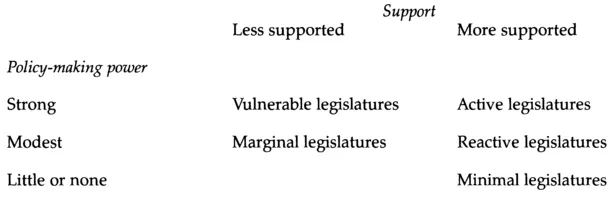

This study explores the relationship between parliaments and government through exploring two hypotheses. The first concerns the basic relationship of parliament to government. Scholars such as Michael Mezey have offered taxonomies of legislatures based on their policy-making power. Mezey distinguishes three types, those with strong, modest or little (or no) policy-making power.3 He categorises these respectively — in polities where the legislature enjoys support at both mass and elite level — as active, reactive and minimal legislatures (Figure 1.1). The US Congress is offered as the prime example of an active legislature. The British Parliament is offered among the examples of reactive legislatures. The last category houses legislatures in various one-party states.

Our first hypothesis is that the capacity of legislatures to affect public policy is determined by variables largely beyond their control: in other words that the category in which a legislature falls is determined by the external environment. Knowing which category a legislature occupies, and why, is clearly important to an understanding of legislatures, but such knowledge has its limitations. The categories are broad. Furthermore, one of them

FIGURE 1.1 MEZEY'S TYPOLOGY OF LEGISLATURES

Source: M. Mezey, Comparative Legislatures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1979).

is increasingly crowded. When Mezey published his comparative study, there were already many examples of reactive legislatures: he included most of the legislatures of western Europe as well as the leading countries of the Commonwealth (UK, Canada, Australia, India and New Zealand). With the rusting and then destruction of the Iron Curtain, and the restitution of freely elected legislatures in a number of other countries in different parts of the globe, the category of minimal legislatures has shrunk significantly. The other categories have swelled accordingly, especially that of reactive legislatures. We thus have a large number of legislatures with modest policy-making power. Though there is limited literature on many of these legislatures, we know from existing studies that there are differences between them in terms of their capacity to affect policy outcomes. They may share the same basic relationship to government but they differ in the extent to which they can actually constrain government. There is a difference of degree if not of kind. We know from various studies, for example, that the capacity of the Swedish and Dutch parliaments to constrain government differs from that of, say, the British and the French parliaments.4

I have elsewhere identified a ranking within the category of reactive — or what I have termed policy-influencing —legislatures.5 There are strong reactive legislatures, such as that of Sweden; there are middle-ranking reactive legislatures, such as that of Germany; and there are weak reactive legislatures, such as those of Ireland and France. Those at the top of the scale are still reactive legislatures — they respond to what government brings forward, and the government will usually get what it wants — but their capacity to affect government measures is somewhat greater than those lower down in the ranking.

If external conditions determine the category, what determines a legislature's place, or ranking, within a category? Our second hypothesis is that variables specific, or internal, to the legislature can determine its ranking, and that its capacity to influence policy outcomes is greatest when it is highly institutionalised. Institutionalisation, as we shall discuss, has various features, but one of the most salient is that of specialisation. Observation suggests that the legislatures exhibiting the greatest capacity to determine policy outcomes have highly developed committee structures. Woodrow Wilson's classic study of the US Congress in the nineteenth century emphasised the centrality of committees to the work of Congress. They remain central. 'More than any other legislative body in the world, the Congress relies on an extensive committee system to process its voluminous workload.'6 Developed committee systems also appear to be a feature of those west European legislatures nestling in the upper half of the reactive category. Institutionalisation, however, is not solely confined to specialisation through committees. It extends to institutionalisation within committees. Committees can have specific and regular characteristics that appear to strengthen their capacity to scrutinise and influence public policy.7 Among the features that have been variously identified are those of permanence, agendasetting and evidence-taking powers, jurisdictions which are exclusive and parallel existing government agencies, extensive resources, and small and informed memberships. Nor is institutionalisation confined to committees. The chamber can be highly developed institutionally, with agenda-setting powers and well-protected rules governing the conduct of business. Members individually may also enjoy substantial resources as well as some degree of entrenchment through seniority or holding leadership positions.

These two basic hypotheses allow us to explore and explain the relationship between parliament and government, and at the same time to describe and assess the effect of the different means available to parliament to constrain government. As such, the work is designed to be useful in terms of both description and analysis.

The External Environment

The growth of mass and industrialised societies has had a fundamental effect on the relationship between parliaments and governments. The demands emanating from a growing and increasingly differentiated society became too numerous and complex to be processed by large deliberative bodies composed of members who were not specialists in particular sectors of economic and political activity. The growth of organised interests — such as trade associations, trades unions, professional bodies and other sectional interest groups — has been a feature of Western society. These various organisations have sought to defend and promote their interests, at times in competition with other groups. Those interests have been pursued in terms of public policy, with demands being made for the introduction of measures designed to protect or extend existing benefits or status. The focus for such demands has been the executive branch. Government has acquired the institutional resources to process such demands. The greater and more complex the demands, the greater the dependence of government on external groups for information and advice. The greater and more specialised the demands, the greater the specificity of government policy.

The effect has been to confirm or to shift the onus for formulating — or 'making' — public policy onto government. Whatever the formal status of the legislature, the principal measures of public policy emanate from the executive. Even in the United States, with a legislature that constitutes, in Michael Mezey's words, 'one of the few legislative institutions in the world able and capable of saying no to a popularly elected president and making it stick',8 the principal measures are those emanating from the president; to say 'no' to something entails a proposal having been brought forward.

Despite the popular association of legislatures with 'law making' — an association derived from the very name of the institution9 — legislatures are not so much law-making bodies as, in David Olson's apt phrase, 'law effecting' bodies.10 That characteristic is common to all legislatures. The extent to which legislatures can actually determine outcomes is decided by their relationship to government. Government formulates policy and brings forward measures that it wishes to be binding on society. Legislative power, in pluralist terms, is the capacity of the legislature to constrain government in what it does. The extent to which parliaments can constrain governments — what Jean Blondel has conceptualised as the viscosity of legislatures11 — is determined essentially by variables external to parliaments. Those variables determine the basic relationship of parliament to government.

The most important variables fall under three headings: cultural, constitutional and political. The political culture, the amalgam of attitudes built up over time towards society and the running of that society, will shape both the constitution and how people behave politically. Attitudes derived from the experience of British rule motivated the founding fathers in America to craft a political system that diffused political power. An ideological consensus in the USA — believed to result from the absence of a feudal history — has militated against the emergence of parties with strong ideological bases.12 Very different political cultures have pervaded western Europe. Those cultures have variously changed, sometimes gradually, sometimes dramatically (for example, as a result of war). Consequently, constitutions have varied significantly, both between countries and over time.

The constitution of a country will stipulate the relationship between the different parts of the political system at both the horizontal level (a presidential or parliamentary system, or some variant) and the vertical level (a unitary or federal state). It will determine the form of the legislature (unicameral or bicameral) and may adumbrate the powers of the legislature. It will stipulate the type of electoral system to be employed as well as the categories of people eligible to take part and the method of election (secret or open ballot, regularity and timing) and the extent of election (one or both chambers, the president alone or the president, vice-president and other officers). It will delineate the role of the judicial branch in constitutional and statutory interpretation. The constitution thus establishes the place of the legislature in the nation's formal political structure.

The position established by the constitution is necessary but not sufficient for explaining the power of legislatures. One has to identify political variables. The foremost variable is the party system. Some constitutions recognise political parties but most do not. The leverage exerted by political parties is determined largely by features of the constitutional framework, most notably the electoral system, and by the nature of society (for instance, whether homogeneous or fragmented). It may also be influenced by laws regulating the conduct of parties.13 Some electoral systems, notably the first-past-the-post (FPTP) syst...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- General Introduction

- 1. Introduction: The Institution of Parliaments

- 2. Old Institution, New Institutionalism? Parliament and Government in the UK

- 3. The German Bundestag: Influence and Accountability in a Complex Environment

- 4. The Italian Parliament: Chambers in a Crumbling House?

- 5. Parliament and Government in Belgium: Prisoners of Partitocracy

- 6. A Changing Relationship? Parliament and Government in Ireland

- 7. Relationship between Parliament and Government in Portugal: An Expression of the Maturation of the Political System

- 8. The European Parliament: Crawling, Walking and Running

- 9. Conclusion: Do Parliaments make a Difference?

- Index