- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

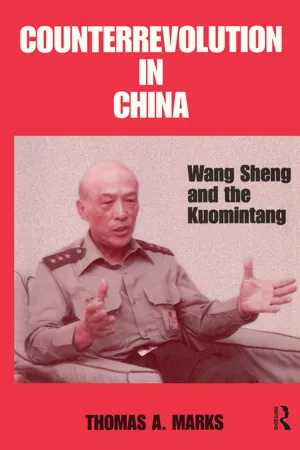

About this book

This ground-breaking book spans 60 years of modern Chinese history from the much neglected non-communist perspective. Concentrating on Wang Sheng's career in relation to Chiang Kai-Shek's extraordinary son Chiang Ching-Kuo, it shows that the KMT were perfecting the methods that were to make Taiwan an East Asian Tiger' economy at the very point that they lost' the mainland. The book also provides a fascinating insight into Taiwan's efforts to aid South Vietnam and Cambodia from 1960 as the Indochina war unfolded.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Counterrevolution in China by Thomas A. Marks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The End of an Era

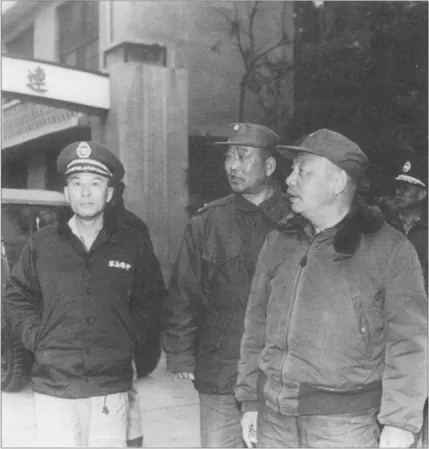

Inseparable duo: Chiang Ching-kuo (center front) and Wang Sheng (left) during 1967 inspection of the offshore islands.

ON 10 MAY 1983, a day apparently of no special note in the Republic of China, the country’s president, Chiang Ching-kuo, asked Wang Sheng to come to his office in Taipei. The brief telephone call to Wang, the general who headed the military’s General Political Warfare Department, or ‘GPWD’ as it was often termed, was a normal thing.1 The two men had known each other for half a century. To many, in fact, they were the numbers one and two – respectively – in the political hierarchy of the Kuomintang, the Nationalist Party, ‘the KMT’, which, in exile from China, had constructed and ruled the de facto island-state of Taiwan.

As he entered the room, Wang, then 67, saluted and said, ‘Mr President, how are you?’, to which Chiang replied, ‘Director Wang’. It was a ritual which had been repeated innumerable times. Only five years apart in age, they were nonetheless separated by an immense gulf. For all the talk of relative positions in the KMT hierarchy, it had always been like this, one the teacher, one the dutiful pupil, the very relationship of their meeting those long years ago in China’s Jiangxi province, cradle of the communist revolution of which they were both firm foes.

So much had happened in the intervening years, yet so much had stayed the same: two figures whose personal relationship remained defined by their relationship to their country. For the previous eight years, those during which Wang Sheng had been the official head of GPWD, he had in public been ‘Director Wang’. Chiang Ching-kuo had been ‘President Chiang’. When they were alone, Chiang often became ‘Education Director’, the position he had held those many years previously in Jiangxi. Wang Sheng became ‘Hua-hsing’.

That, of course, was not the name his parents had given him, which was Wang Shiu-chieh. But that name had disappeared along the way. Wang Sheng was the student name which had stuck. Another teacher, though, had taken to calling him Wang Hua-hsing, so sometimes Chiang Ching-kuo called him that. Or he would use the two titles that Wang Sheng had held while Chiang’s direct subordinate in the Political Warfare hierarchy, ‘Chief of Education Wang’ or Assistant Commandant Wang’.

Yet this time it was ‘Director Wang’. And ‘President Chiang’ motioned to the sofa. Wang Sheng sat on the left, Chiang on the right. Not well – driven by diabetes, his health had been in serious decline for several years – Chiang Ching-kuo was very serious.

It had been but several weeks since Wang Sheng had returned from a short trip to the United States at the request of the unofficial US Embassy, the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT). Aside from the usual gossip occasioned by the timing, the whole business had seemed uneventful enough.

Certainly the inevitable carping and criticism, though, had proved irritating. The name Wang could also mean ‘king’, and Sheng could mean ‘raise’ or ‘to rise up’. Hence, as Chiang Ching-kuo deteriorated, went the gossip, Wang Sheng, or ‘Rising King’, was moving to solidify his position with the Americans so that there would be no disruption, come the transfer of power, in the Republic’s relations with its chief international backer.

Ironically, the trip had been cleared by Chiang Ching-kuo himself. The timing had been right. After three difficult years of ‘extra duty’, heading a special body set up by President Chiang to coordinate Taiwan’s response to China’s united front assault, Wang Sheng had found himself back in his familiar GPWD routine when Chiang abruptly terminated the ’Liu Shao Kang Office’. The American invitation, apparently stemming from Washington’s own perception of Wang’s position in the ruling KMT hierarchy, had been pressed since ‘derecognition’ of Taiwan in favor of the mainland in 1979. Sensing the need for a break, all concerned had agreed that the time had come to accept.

As far as such episodes went, the Wang Sheng tour was decidedly low key. Accompanied by only a single interpreter and his wife, Wang Sheng had met with American officials and academics concerned with Taiwan and China. At one point the issue of the presidential succession came up, in response to a question asked by the scholar A. Doak Barnett. Wang replied that Chiang Ching-kuo’s health was good, his mind clear; and, in any eventuality, the ROC constitution, which stipulated that the vice-president would step into the shoes of the president should such become necessary, would dictate events.

That the issue of the transition was openly broached by the Americans to Wang had created some stir in Taiwan, but both the question and the response had been straightforward. It was reported in a regular communication sent back to Taiwan.

When he returned, Wang Sheng discussed his trip directly but briefly with Chiang Ching-kuo. The president seemed different in a vague sort of way, a bit cold, but that could be attributed to his continuing illness. Wang Sheng thought nothing more of it and went back to his work. There were no meetings between the two.

Fateful visit: Wang Sheng is greeted by William Casey, Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), during his brief 1983 trip to the US.

Now, in May, they made small talk. Then Chiang Ching-kuo came to the point. ‘You’ve been doing the same job for too long’, he said, ‘so we’re going to transfer you to a position in armed forces joint-training’. A few more words, and the meeting was over. It had lasted just five minutes.

Thus ended one of the most powerful, though certainly one of the most ambiguous, careers in the long history of the KMT and the system it sought to build and protect. ‘Rising King’ had fallen, summarily and completely, ushering in a new phase of the Republican revolution.

In retrospect, one has images of storm clouds gathering and ominous portents, followed by the climactic struggle. Reality was far more prosaic.

Even the sacking was lacking in drama. For Chiang Ching-kuo had said nothing of demotion or disgrace. He had spoken only of a general being transferred. Certainly Wang Sheng was no ordinary general, as we shall see, but he was, in the final analysis, just a general filling a billet. Moving to another position would have been unusual, given Wang’s singular involvement with Political Warfare, but not extraordinary.

There was even a certain logic to the meeting. Three years earlier, just before Liu Shao Rang had been established, Chiang Ching-kuo had asked Wang Sheng to his house for a friendly chat. At the time, Wang was thinking about how he could get a new job. ‘I was running Political Warfare’, he was to observe later. ‘This was very wearing. You’re the guardian for the whole military. Any night the phone would ring, I’d jump up, frightened, knowing there might be some disaster’.2

Wang Sheng, a product of a military sense of duty and a Chinese sense of obligation, could not directly tell Chiang Ching-kuo, his superior and lifelong teacher, that he did not want his job anymore, so he tried to find another way. Referring to the time when Chiang had been GPWD head, and Wang the deputy, he said, ‘When you took this job the first time, it was for a two year term. When you stayed on, it was for only another term. You left in order to keep things legal. Next year I’ll have been here three terms. If I continue to stay on, I’ll violate the system’.3

Chiang Ching-kuo, though, did not see the connection Wang Sheng was trying to make and said only, ‘It is a difficult question but another problem’.4

Then, after a few days, he called Wang Sheng and said that he had checked the matter out: ‘There is no statutory limit on the head of the Political Warfare Department. Term limits were just something we had assumed existed’.5

That was the end of the issue. Wang Sheng was unable to get himself to ask formally that he be given a new assignment. Nevertheless, he did not let the matter drop. In particular, when Chiang Ching-kuo directed him to set up Liu Shao Rang, Wang tried his mentor’s patience by seeking to decline. In the end, the fateful chain of events was set in motion.

When Chiang Ching-kuo finally called Wang Sheng in, however, that eighth year as Director of GPWD, and told him that he had been there too long and was being given a new job, it did not seem ominous. Indeed, Wang was relieved. He needed a change. Tine’ was all the response he mustered.

‘For sixteen years I had been the deputy director and executive deputy general beneath Chiang Ching-kuo’, he recounts, ‘then eight years as the director, a total of 24 years of very difficult work. So I felt as though ten thousand pounds had been lifted from my shoulders’.6

Wang Sheng returned to his office. Immediately thereafter, the transfer order was announced. He was to become the Director of Joint Operations and Training. Finally, Wang was stunned: ‘If I had been transferred to a very important position, such an action would have been comprehensible, but I had been transferred to a very insignificant position’.7

There now was no doubt that the action was considered extraordinary. No time was allowed for a normal rotation. The GPWD Executive Officer, a lieutenant general, was not even in Taipei but in the southern part of the island participating in a field exercise. The Chief of the General Staff, Hau Po-tsun, was also there to watch the exercise.

A reaction to the announcement started immediately. The Chief of Staff heard the news and called back to Wang Sheng’s office. He said that the change had caused uneasiness among the troops and suggested that Wang meet him immediately to calm matters and to plan an orderly transition. Wang briefly demurred, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of Maps

- List of Figures

- Preface

- 1. The End of An Era

- 2. Jiangxi: The Making of a Counterrevolutionary

- 3. Civil War: Competing Revolutions

- 4. Taiwan: Revolution in Exile

- 5. Counterrevolution Exported

- 6. Strategic Counterrevolution

- 7. Paraguay: Back to Jiangxi

- 8. A New Era?

- Bibliography

- Index