- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

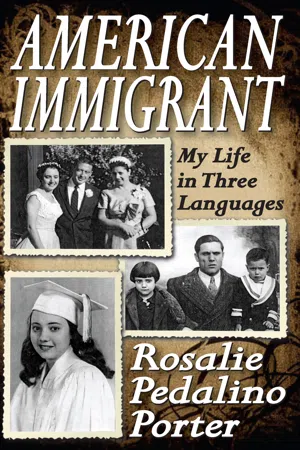

Immigration is one of the most contentious issues in twenty-first-century America. In forty years, the American population has doubled from 150 to 300 million, about half of the increase due to immigration. Discussions involving legal and illegal status, assimilation or separatism, and language unity or multilingualism continue to spark debate. The battle to give five million immigrant children America's common language, English, and to help these students join their English-speaking classmates in opportunities for self-fulfillment continues to be argued. American Immigrant is part memoir and part account of Rosalie Pedalino Porter's professional activities as a national authority on immigrant education and bilingualism.Her career began in the 1970s, when she entered the most controversial arena in public education, bilingualism. This book chronicles the political movement Porter helped lead, one that succeeded in changing state laws in California, Arizona, and Massachusetts. Programs that had segregated Latino children by language and ethnicity for years, diminishing their educational opportunities, were removed with overwhelming public support. New English-language programs in these states are reporting improved academic achievement for these students.This book is also Porter's testament to the boundless opportunities for women in the United States, and to the unique blending of ethnicities and religions and races into harmonious families, her own included, that continues to be a true strength of the United States Porter examines women's roles, beginning in the 1940s and continuing through the millennium, from the vantage point of someone who grew up in a working-class, male-dominated family. She explores the emotional price exacted by dislocation from one's native land and traditions; traveling and living in the Middle East, Europe, and Asia; and the evolving character of marriage and family in twenty-first-century America.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Immigrant by Rosalie Porter in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781351532716Subtopic

World HistorySection III

Parallel Lives, Power Shifts

Chapter 6

An Enduring Partnership Begins

May 13, 2004—Lee and Dave Porter, son Tom with his 13-year-old stepson, David Gamliel, are seated in Albert Long Hall on the Bogazici University campus in Istanbul, Turkey. Professor Oya Basak regales the audience with a long, witty introduction of the concert pianist, Stephen Porter. Oya has been a close friend of the Porter family for four decades. Among the audience of Turkish university students are a dozen American friends of the Porters who, by coincidence or by design, are on hand for the concert. It is a moment of supreme joy for this family whose origins are here, at the place once known as Robert College.

The Turkish Years

August 15, 1957: The honeymoon voyage begins. The ocean crossing on the SS Independence was a restorative interlude. On arriving in Italy, we spent a full week in Rome and Capri, and had a short visit with lo zio Giacomo in Naples. My uncle and his family were surprised but happy that I had married the young American who had been my companion on my madcap adventures four years earlier. We sailed for Turkey on the Lloyd-Triestino Lines’ San Giorgio, a small ship that followed a romantic course from Naples through the Corinth Canal to Athens; then on to Izmir, the Dardanelles, and to dock in the Sublime Port—Istanbul, once Constantinople.

In these special circumstances, when we were leaving our former lives, families, and friends to take up new roles in a relatively unfamiliar part of the world, the leisurely pace of intercontinental travel permitted time for us to make a comfortable transition. Once the days of transoceanic travel by ship passed into obscurity in the 1970s, the jet-propulsion of hordes of travelers around the planet eliminated the comfort, romance and exoticism of earlier voyages.

Docking in Piraeus, for example, for the obligatory half-day visit to Athens and the Acropolis, gave us a second chance to admire this marvel of human ingenuity at close range, to walk among the gigantic caryatid columns, a physical proximity no longer allowed to tourists. On our return to the San Giorgio, we left our camera in the taxicab. Dave ran back to try to catch the driver, who was speeding away from the docks, while I boarded the ship. Within minutes, the “all ashore” sounded, and the crew prepared to raise the gangplank. For one horrifying moment I thought we would set sail without my husband, and he’d be stranded without his passport! One second before the gangplank was uncoupled, Dave ran across the pier and leapt on board.

It was thrilling to arrive in Istanbul again, to be met officially this time as members of the Robert College community, once the truly Byzantine customs and immigration formalities were completed. David had been hired to head the English Department for Robert Academy, and to be housemaster of Theodorus Hall. Our home for the next two years would be the housemaster’s apartment in that venerable building (colloquially referred to as “The Odorous Hall), together with eighty- nine Turkish teenage boys, two American resident teachers, and two Turkish tutors. When we arrived at the door of our quarters, David carried me over the threshold, a gesture I treasure. There was not time to take more than a swift glance around and freshen up for dinner at Will and Doris Whitmans house, a short walk away from the campus quadrangle. On our return, we postponed a close examination of the apartment for the next morning; we were utterly enervated by the days tensions. Our bedroom was equipped with two old Army cots and a small chest of drawers. Our bathroom included a claw-foot tub and a makeshift shower attached to a copper hot water heater fueled by a wood fire that we were too exhausted to attempt at that hour. As I curled up alone on my little cot, I was suddenly swept by a tremendous homesickness, anomie. What was I doing in this strange place, and who was this man I had promised my life to? I wept in muted anguish until my husband comforted me with this gentle reassurance: “We’re going to be all right, Zelda.”

A bright, sunny morning restored our spirits. Our living quarters, three large rooms with magnificent views of the Bosphorus from every window, were almost entirely bare of furnishings. The kitchen had a two-burner electric hotplate set on a marble-topped chest of drawers. No utensils, silverware or crockery, no stove, and no refrigerator. David had been expected to arrive as a bachelor who would take all his meals in the college dining room. Though we were warmly welcomed in the faculty dining room, we soon decided that we wanted our privacy at meals. The challenge would be to set up a workable situation in the housemaster’s apartment at a time when supplies of consumer goods were severely depleted, a situation for which we were not well prepared. Since our hasty marriage and rapid departure from America had taken the Robert College administrators unawares, there had not been time to warn us about what useful supplies to pack in our trunks.

The Turkish government, in the mid-1950s, launched an ambitious program to improve the country’s economy by building highways, commercial sites and housing, and by laying pipelines for oil and gas delivery. In order to promote these national priorities, practically all imports of consumer goods were severely restricted in order to favor the import of steel, concrete, and other essentials. Local industries were not yet advanced enough to produce the things we take for granted in Western countries. We could not, therefore, go to downtown Istanbul and buy a refrigerator or a stove or sturdy cooking utensils or any but the most poorly made dishes and glasses. Turkey had not yet begun to produce frozen foods and very few canned fruits and vegetables were on the market. No foreign alcoholic products were imported. But the one unavailable item that was most distressing for natives and foreigners alike was the lack of coffee. For the entire two years of our residence in Turkey, there was no coffee on the market. The Turks, who had treated the world to Turkish coffee for five hundred years, were now reduced to drinking only tea, a situation deeply resented but tolerated. It was pure luck that my mother, the good Lucia, had slipped four cans of American coffee among our clothes in one of the trunks! The only household goods we were bringing with us were eight place settings of silverware and a chrome-plated electric coffee percolator.

Our first few days on campus, before the arrival of students and faculty, were devoted to organizing our household. No friend in Orange, New Jersey, could have imagined the scenes we faced—the deep disappointments that were more than balanced by the generous spirit of the Robert College community. First priority was to make our needs clear to the woman in charge of allocating college furnishings, the admirable Mrs. Armen Turgil. She managed to provide us with a real bed and a tiny kitchen stove within days, but we were without a refrigerator for three months. In the warm early fall, I kept butter, milk, and other perishables in the refrigerator of Ann Milnor, wife of the Robert Academy principal, and made the short walk to their home, up and down hill, several times a day.

Our first visit to the on-campus bakkal, or what I expected to be a grocery/convenience store, totally shocked me. We entered a dusty, dim room with a wooden counter and shelves that were entirely empty. In front of the counter was a huge sack full of rice and another full of dry beans. On the counter stood a scale, a cash box, a stack of newspapers for wrapping purchases, and a few loaves of bread. As we walked out, I fought to restrain tears of incredulity. We would have to obtain our groceries, meats, and produce from the nearby village of Bebek, a long trek up and down the steep Robert College hill.

Another surprise was the status of the local meat supply and the quality of butchering. If the butcher in Bebek had any meat at all, it was hung on a hook outside his small shop, unrefrigerated. It might be a side of beef, but most often it was lamb or mutton. There was no differentiation between cuts of meat—when the butcher understood how many kilos of meat we wanted, he would hack off a chunk and slap it into a newspaper. It would be up to me to make something out of it. Without a car, we walked down the steep hill to the village and carried our purchases home with us in string bags. On occasion we would be offered a ride on our friend Claren Sommer s scooter or in his tiny car, a British Lloyd two-cylinder that barely made it up the hill with two people in it. For the most part, we made the trek on foot.

Many new acquaintances loaned us basic china and glasses, and some sturdy pots and pans. But most importantly they gave us a wealth of information on how to manage the daily routines. I learned to be ready with a saucepan when the sutcu (milkman) arrived every evening on his donkey. He came to the door to measure out a liter or two of milk and pour it into my saucepan, for which I paid him some few kurus. With the aid of a borrowed cooking thermometer, I heated the milk to 120 degrees for 20 minutes—voila, it is pasteurized! I telephoned each evening to the green grocer in Bebek for fresh fruits and vegetables that would be delivered the next morning, saving me some of the walking trips. I was put in touch with the tavukcu (chicken man), an enterprising youth who called on us every few weeks. Into my kitchen he carried his little suitcase, opened it to unpack several small packages wrapped in newspapers—a scrawny chicken weighing no more than a pound and a half at best, a piece of highly seasoned salami. We haggled a bit over the price, in a good-natured fashion, and the purchase was made.

As we began attending faculty dinner parties I realized that, without canned or frozen foods, we were all limited to the same three or four vegetables in season. Wonderful as the fresh, naturally ripened produce was, we found ourselves keenly eyeing the market for the next seasons bounty, for the first strawberries or spring peas. My first attempt at making a fruit pie had me following instructions in my new Betty Crocker cook book, the best basic “how to” for wives of the 1950s. I discovered a new product in Bebek, canned sour cherries. After tossing the cherries with sugar, cinnamon, and a little lemon juice, I decided to taste one and, to my surprise, I bit down hard on a cherry stone. The processing of cherries did not yet include removing the pits! I did not mind the extra half hour spent on removing every cherry stone since it would have been terrible if we had put our guests at risk of breaking a tooth.

We were a very traditional, friendly community, with every one of the established families entertaining the newcomers and extending all manner of assistance and advice—from references to doctors, ways of getting around without cars, and how best to pazarluk (that is, to bargain the price of goods in the Grand Bazaar) to organizing sightseeing tours on weekends. Social events on campus included afternoon teas, bridge parties, dinner parties, cocktail parties, musical or dramatic performances by the faculty, or special performances by visiting dance companies, musicians, and theater groups. We had an introduction to a Turkish businessman who had dealings with our brother-in-law in New York. Albert Ben Muvar and his wife Laurette turned out to be a delightful young couple with lively interests in the social life of the city. They were our guests at a number of Robert College events, and we met them in the city on occasion. One evening at the Karavansarai Night Club, when the band struck up a Charleston, my husband announced that I was a noted Charleston dancer. Albert swept me out to the dance floor. He was an incredible dancer and the floor was immediately cleared for the two of us. We had such fun kicking up our heels at the fast rhythm and received loud applause at the end.

Learning to be a housewife in such a daunting situation forced me to rely on the advice of cooperative friends, not on the gadgets we would have considered essential back in the states. We made do with so little of the conveniences in American homes and were proud of it. For example, I made my own peanut butter, and rolled up balls of tel kadayifznA baked them in the oven to make a faux shredded wheat cereal, but the oddest thing I learned to make was vodka. Turkish vodka was the only “hard liquor” available on the market, besides Raki, but it was very expensive. Tobacco shops sold pure alcohol, legally. I was instructed in the simple art of making vodka at home. “One liter of distilled water boiled with a small amount of sugar; let cool and add one liter of alcohol and the thin peel of one lemon. Strain through a clean cloth, put in bottles and store in a cool, dark place.” The vodka might be aged for only a few hours if we were having a party that night, or it could be stored for a longer time to achieve a smoother quality. And so it was that I became the vodka maker in our family for the next two years, mixing it with fruit juice and Portakal liquor to produce the “Hill Cocktail” of Robert College lore.

Being so far from both Pedalino and Porter families allowed us to work out the foundations of our married life in ways that would not have been possible if we had had the interference of our two totally different clans. Some of those strains emerged later when we moved back to the United States, but by then we had bonded in a relationship that promised to be sturdy enough to withstand the stressful times.

One of the festering, unresolved issues hanging over us during those first two years was the matter of our uncompleted marriage, that is, our civil ceremony before a U.S. Justice of the Peace, which did not meet my expectations as a Roman Catholic for a true sacramental blessing by my church. The few days between David s marriage proposal and the beginning of our lengthy voyage to Istanbul gave me an excuse to leave the matter in limbo. Shortly after arriving at Robert College, I raised the question of when we would have a religious ceremony. David drew back from the vague promise he had made earlier. I felt sadly disappointed that my understanding had perhaps been more wishful thinking than a real commitment from my husband. We faced the same dilemma that had stopped us from marrying a year earlier: the Catholic Church made very firm demands on non-Catholics: the couple would not employ artificial birth control; the non-Catholic partner would not interfere with the Catholic partners practice of faith; the couples children must be baptized and raised in the Catholic faith. For David, the third requirement was the most repellant, although he found the first two unappealing as well.

In our first year at Robert College I tried to attend Mass at the tiny Armenian Church in the village nearby but on each of these occasions David would express his disapproval by his silent sulks. Even a polite discussion of the problem became increasingly emotional. My husbands firm agnostic principles would not allow him to impose any religious beliefs and practices on our future children—that was it, plain and simple. I felt aggrieved at being deprived, essentially, of my faith. We could not live together very long without a compromise on someone’s part. I reasoned, privately, that I had but two choices: either I should divorce my beloved husband in order to remain a Catholic, or I should put aside my religious practices and keep my commitment to the intelligent, moral husband I had come to love and appreciate. Was this a foolish rationalization? Perhaps. Was my capitulation wise? Yes, in light of the subsequent years of a strong, loving partnership of immensely greater satisfactions than I could have imagined at that time. We changed each others attitudes significantly over those years.

The women, the faculty wives with whom I formed strong attachments and for whom I had the greatest admiration as exemplary wives and mothers—my role models—appeared to be of uniform composition. All shared middle-class, Protestant backgrounds, all were graduates of prestigious colleges—strong representation from Smith and Mount Holyoke—all expressed liberal political views. I was not the brunt of any overt social-class snubs, but still I felt out of my element. I wanted to be one of them but knew that I could not change myself, retroactively, to fit their mold. We openly discussed housekeeping minutiae, shared books and magazines that were in short supply, traded ideas on world events and U.S. policies and politics, but they deemed some topics—birth control or abortion, for instance—unsuitable to be brought up in my presence. They all were engaged in part-time teaching, which I was unqualified to do. One day I overheard a silly conversation between two of my women friends with small children. One of them said she had asked her four-year-old daughter what she wanted to be when she grew up and her daughter answered, “An airline stewardess and fly all around the world.” At that they both laughed and the other woman said, “She’ll grow out of it, not to worry.” Since that was my last job before marrying, I felt demeaned.

David and I began an unlikely friendship with a young couple teaching at the nearby Kiz Kolej (American College for Girls), the sister school for Robert College located a few miles away. We had first met David and Mary Alice Sipfle on the ocean crossing and soon after we began to have an occasional dinner together. They were both recent graduate students from Yale, David had completed his doctorate in philosophy and Mary Alice all but her dissertation for the doctorate in French. We were an unlikely foursome. The Sipfles were intellectually stimulating, polished conversationalists with a sharp sense of humor, good Bridge players, but they were teetotalers. We were more sophisticated in the ways of travel, social life, partying, drinking, smoking. We found common ground in a love of good food and our evenings centered on a well-cooked dinner and hours of Bridge, with good conversation. The Sipfles had brought a Virginia ham with them, a real treasure in a Moslem country, and it hung from the ceiling in their kitchen as a prized possession. After Mary Alice delivered their first child, Ann, and recovered her energy, we were invited to be their guests for a Christmas dinner that featured that precious ham.

The Sipfles were destined to have the most profound influence on both of us. Dave Stipfle s example as a talented teacher and intellectual became one of the prime factors in my husband s decision to pursue a doctorate in literature and a career in university teaching when we returned to the United States in 1959. Mary Alice presented me with a competitive challenge, planting a seed that would lie dormant for a dozen years or more before sprouting. I did not at that time ask myself if I could one day complete my studies for an undergraduate degree, much less a doctorate like Mary Alice, but I felt a subconscious stirring in that direction. Also, the two proudly stated that their marriage was firmly based on the notion of a 50-50 sharing of domestic duties. What an amazing idea in 1958, even for a liberated academic community, that a husband would take turns diapering the baby, washing dishes, giving the baby an early morning feeding and occasionally allowing his wife to sleep late. It was certainly a way of life that my husband would not dream of embracing. A rigid, gender-based division of duties would prevail well into the future for us.

Domestic issues aside, it was an exhilarating time to be living in the Near East, next door to the USSR, which celebrated the fortieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution in November 1957 by launching the first projectile into space, the Sputnik. Turkey represented our strongest ally, allowing the United States to maintain naval and air bases on its soil, bases for the constant aerial surveillance of the Soviet Union. The Bosphorus, the deep-water linkage between the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmora and the Mediterranean, flowed beneath the Robert College hill, affording us daily views of Russian oil tankers, probably ships carrying KGB spies, part of our Cold War mentality.

The U.S. military presence was barely visible, but access to the goods sold on the American bases was a wildly sought-after benefit. One of the most intense topics of gossip in our college community was the question of who among us had “PX privileges.” Who among the college administrators had the privilege of going to the stores maintained on the U.S. military bases, the Post Exchanges, for service men and their families? Since so few consumer goods were available in local markets, the appearance of coffee or Scotch or a canned ham raised suspicions among the rest of us. There was almost no social mingling of the college community and the American military families. It was understood that the military considered Istanbul a hardship post and could not imagine why any Americans would actually choose to live here. Someone once overheard the Robert College people referred to by an Air Force officer as “civilian slop-over.”

We also won...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- title

- copy

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Prologue

- Section I—Early Years, Early Struggles

- Section II—Earning A Living, Getting A Life

- Section III—Parallel Lives, Power Shifts

- Section IV—Transformations, Resolutions

- About the Author

- Appendices

- Endnotes