![]()

1Technological Stigma1

Robin Gregory, James Flynn, and Paul Slovic

The word “stigma” was used by the ancient Greeks to refer to a mark placed on an individual to signify infamy or disgrace. A person thus marked was perceived to pose a risk to society. Within the social sciences, there exists an extensive literature on the topic of stigma as it applies to people. By means of its association with risk, the concept of stigma recently has been generalized to technologies, places, and products that are perceived to be unduly dangerous.

Stigma plays out socially in opposition to many technological activities, particularly those involving the use of chemicals and radiation, and in the large and rapidly growing number of lawsuits claiming that one’s property has been devalued by perceptions of risk. For example, in 1993 in Criscuola et al v. New York Power Authority, the New York State Court of Appeals ruled that landowners whose property is taken for construction of high-voltage power lines can collect damages if the value of the rest of their property falls because of public fears about safety, regardless of whether that fear is reasonable. In City of Santa Fe v. Komis, the Supreme Court of New Mexico in 1992 upheld the award of $337,815 to a Santa Fe couple for diminished property value resulting from the proximity of their land to a proposed transportation route for transuranic wastes. These and other similar cases have received national attention because they explicitly link public perceptions of a technological hazard with monetary compensation for a possible future decline in economic value.

This form of stigma has risen to prominence as a result of increasing concern about the human and ecological health risks associated with the use of technology. But stigma goes beyond conceptions of hazard. It refers to something that is to be shunned or avoided not just because it is dangerous but because it overturns or destroys a positive condition; what was or should be something good is now marked as blemished or tainted. As a reporter for Time Magazine commented in reference to a food contamination scare, “The most deep-seated fears are engendered when the benign suddenly turns menacing.” As a result, technological stigmatization is a powerful component of public opposition to many proposed new technologies, products, and facilities. It represents an increasingly significant factor influencing the development and acceptance of scientific and technological innovations and, therefore, presents a serious challenge to policymakers.

Stigma reminds us that technology, like the Roman god Janus, offers two faces: One shows the potential for benefit, the other shows the potential for risk. The existence of stigma reflects a widespread social concern about the risks from technology and provides evidence of an expectation that has not been met or a reputation that has become tarnished.

In this sense, scientific and technological prestige might be viewed as the opposite of stigma. For example, the fierce nationwide competition for the superconducting supercollider project was motivated in part by the prestige of hosting one of the world’s most advanced scientific and technological research facilities. This shows that stigma is not an inevitable outcome of technological advance; it exists only when something has gone awry, so that prestige is replaced by fear and disappointment.

Characteristics of Stigma

The impetus for stigmatization is often some critical event, accident or report of a hazardous condition. This initial event sends a strong signal of abnormal risk. Roger E. Kasperson and colleagues have shown that the perceived risks of certain places, products and technologies are amplified by the reporting power of the mass media. Negative imagery and negative emotional reactions become closely linked with the mere thought of the product, place, or technology, motivating avoidance behavior. A theoretical model developed by one of us (Slovic) and his colleagues demonstrates how images of a place or product affect its desirability or undesirability, consistent with models used in the marketing and advertising world.

Stigmatized places, products, and technologies tend to share several features. The source of the stigma is a hazard with characteristics, such as dread consequences and involuntary exposure, that typically contribute to high perceptions of risk. Its impacts are perceived to be inequitably distributed across groups (e.g., children or pregnant women are affected disproportionately) or geographical areas (one city bears the risks of hazardous waste storage for an entire state). Often the impacts are unbounded, in the sense that their magnitude or persistence over time is not well known. A critical aspect of stigma is that a standard of what is right and natural has been violated or overturned because of the abnormal nature of the precipitating event (crude oil on pristine beaches and the destruction of valued wildlife) or the discrediting nature of the consequences (innocent people are injured or killed). As a result, management of the hazard is brought into question with concerns about competence, conflicts of interest or a failure to apply proper values and precautions. Specific examples of technological stigmatization demonstrate the importance of these features and the sometimes devastating effects of stigma.

Public evaluations of advanced technologies tend to be ambiguous, are often inaccurate and can, as such, contribute to the stigmatization of the technologies. It is not surprising that nuclear energy—touted so highly in the 1950s for its promise of cheap, safe power—is today subject to severe stigmatization, reflecting public perceptions of abnormally great risk, distrust of management, and the disappointment of failed promises. Certain products of biotechnology also have been rejected in part because of perceptions of risk; milk produced with the aid of bovine growth hormone (BGH, or bovine somatotrophin, BST) is one example, with many supermarket chains refusing to buy milk products from BGH-treated cows. Startling evidence of stigmatization of one of the modern world’s most important classes of technology comes from studies by Slovic and others asking people to indicate what comes to mind when they hear or read the word “chemicals.” The most frequent response tends to be “dangerous” or some closely related term such as “toxic,” “hazardous,” “poison,” or “deadly.”

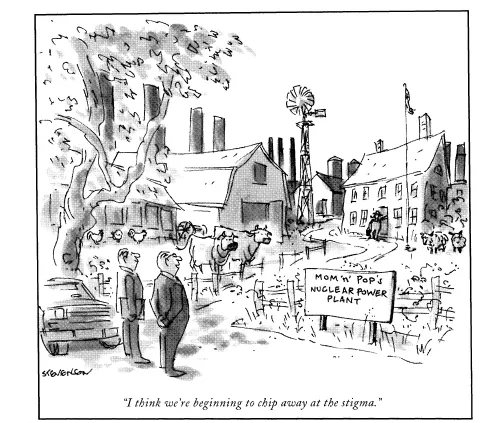

Figure 1.1 An improbable approach to managing stigma is depicted in this 1988 New Yorker Magazine cartoon. © The New Yorker Collection 1988 James Stevenson from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved.

Stigmatization of places has resulted from the extensive media coverage of contamination at sites such as Times Beach, Missouri, and Love Canal, New York. Other well-known examples of environmental stigmatization include Seveso, Italy, where dioxin contamination following an industrial accident at a chemical plant resulted in local economic disruptions estimated to be in excess of $100 million, and portions of the French Riviera and Alaskan coastline in the aftermath of the Amoco Cadiz and Exxon Valdez oil spills.

Because stigmatization is based on perceptions of risk, places can suffer stigma in advance of or in the absence of any demonstrated physical impacts. More than a dozen surveys we conducted in Nevada during the past decade show that a majority of Nevadans are worried that the Las Vegas tourist industry might suffer from negative imagery associated with plans to construct the nation’s first geologic repository for high-level nuclear wastes at nearby Yucca Mountain. In Tennessee, opposition by the governor and state legislature to a locally supported monitored retrievable storage (MRS) facility for high-level nuclear wastes was based on their fear that announcement of the facility would impose a negative and economically harmful image on the Oak Ridge region. The governors of Utah and Wyoming have both cited potential tourism losses as reasons for rejecting proposals for locating an MRS facility in their states.

The stigmatization of products has resulted in severe losses stemming from consumer perceptions that the products were inappropriately dangerous. A dramatic example is that of the pain reliever Tylenol. Mark Mitchell estimated that, despite swift action on the part of the manufacturer, Johnson and Johnson, the seven tampering-induced poisonings that occurred in 1982 cost the company more than $1.4 billion. Another well-known case of product stigmatization played out in the spring of 1989, when millions of consumers stopped buying apples and apple products because of their fears that the chemical Alar (used then as a growth regulator by apple growers) could cause cancer. Apple farmers saw wholesale prices drop by about one-third and annual revenues decline by more than $100 million.

Public Policy Implications

Technological stigma raises the specter of gridlock for many important private and public initiatives. The current practice of litigating stigma claims under the aegis of tort law does not seem to offer an efficient or satisfactory solution but rather points to a lack of policy options.

Project developers can, of course, simply pay whatever is asked for as compensation. However, for several reasons this option seems unwise. First, the pay-and-move-on option fails to distinguish between valid claims for compensation and strategic demands based on greed or politically motivated attempts to oppose a policy or program. Second, claims are often made for economic losses predicted to take place years or even decades into the future, despite the many difficulties inherent in forecasting future economic activities or social responses. Finally, this option fails to help us learn, as a society, to understand stigma and to manage it more effectively.

Another option is for proponents or developers to abandon projects threatened by stigma. This would be unfortunate in the many cases where the risks of proceeding are in fact reasonable. Our society’s continued economic and social strength depends on its willingness to accept reasonable risks. The search for safer means to store hazardous wastes and to produce new goods for the marketplace requires us to face difficult trade-offs between new and old sources of risks, costs, and benefits.

One recent response has been to restrict communications that might produce or contribute to stigma. Apple growers in Washington State are suing Columbia Broadcasting System Inc. (CBS) for broadcasting what they claim were false messages about Alar on the network’s 60 Minutes program. The Alar scare has led the Florida legislature to pass a bill allowing Florida growers to sue anyone who says in public that fruits, vegetables, and other food products are unsafe for consumption but who cannot substantiate their claims with scientific evidence. Whatever their merits for specific cases, these anti-disparagement efforts are problematic for policy because they threaten the constitutional right of free speech and may inadvertently limit the ability of people and the media to discuss legitimate concerns about the safety of a product or technology.

Stigma effects might be lessened if public fears could be addressed effectively through risk-communication efforts. However, such a simple solution seems unlikely. In our view, risk communication efforts often have been unsuccessful because they failed to address the complex interplay of psychological, social, and political factors that creates a profound mistrust of government and industry and results in high levels of perceived risk.

We believe the best response is to recognize that stigma is the outcome of widespread fears and perceptions of risk, lack of trust in the management of technological hazards, and concerns about the equitable distribution of the benefits and costs of technology. Technological stigma should be seen as a rational social response to the multiple influences that produce it and therefore as subject to a variety of rational solutions. These solutions must involve thoughtful public policies and active public support. Adopting more open and participatory decision processes could provide valuable early information about potential sources of stigmatization and invest the larger community in understanding and managing technological hazards. This approach might even remove the basis for the blame and outrage that often occurs in the event of an accident or problem. Rather than being seen as unethical or evil, an industry might be viewed as unlucky or even shortsighted, avoiding the moral tainting that exacerbates a stigmatizing event. The active involvement of stakeholders, for example, might have enabled the nuclear industry to begin at a much earlier stage to plan for the disposal of nuclear wastes and to operate within a much less adversarial process.

In recent years, Rodney Fort and others have discussed the idea of offering insurance against the realization of potential stigma effects. We are not aware of any currently existing stigma-insurance markets. However, improvements over time in the ability of researchers to identify and define those factors contributing to stigmatization may make it possible to predict the magnitude or timing of expected economic losses. This could open the door to the creation of new insurance markets and to efforts for mitigating potentially harmful stigma effects.

In cases where fears are great and impacts are extraordinarily difficult to forecast, the developer may have to provide protection against potential losses from stigma. The creation of a stigma-protection option by the New Mexico state government, for example, could guarantee that the value of properties lying along the proposed nuclear waste transportation route would be maintained according to acceptable measures of the market. Such an indemnification strategy would provide an opportunity to monitor expected versus actual market behavior over time: Will the average sale prices of homes near nuclear waste transportation routes actually fall? Will buyers really go elsewhere? In addition, the existence of a program that guarantees market-based values for properties along a transportation route may in itself act to ease public fears and thereby diminish stigma.

Most importantly, the societal institutions responsible for risk management must meet public concerns and conflicts with new norms and new methods for addressing stigma issues. The goal should be to create arenas for resolving these conflicts based on values of equity and fairness. This undoubtedly will require a major reorientation for risk management, reducing the heavy reliance on technical expertise and creating new forms of partnership that allow the public expanded roles in decision making and effective oversight of the risk-management process.

Over time, these and other new policy initiatives may decrease the significance of technological stigma. At the moment, however, stigma effects loom large. In some cases, technological stigma may be so strong as to rule out the use of entire technologies, products, or places. The experience of the past decade has been difficult. The years ahead are likely to add to the growing list of technological casualties unless innovative public policy and risk-management processes are developed and implemented.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been funded by a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and a shared Public/Private Sector Initiative award to Decision Research from the National Science Foundation (NSF; Grant No. SES-91–10592) and the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI).

![]()

2Stigma and the Social Amplification of Risk:Toward a Framework of Analysis

Roger Kasperson, Nayna Jhaveri, and Jeanne X. Kasperson

In March 1996, the British government announced the possibility of a link between a serious cattle disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), and a rare and fatal human neurodegenerative disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD). The announcement was prompted by the discovery of ten atypical cases of the disease, which usually afflicts people over 65, in patients under the age of 42. The government’s announcement provided scant details of the relevant scientific data but noted that they were “cause for great concern” (O’Brien, 1996). The great concern did indeed quickly materialize in the form of an avalanche of press coverage, much of it highly dramatized and speculative. Following on the heels of a decade of ministerial denials, reassurances, and belittling of this potential hazard, the sudden about-face produced an instant crisis and a collapse of public confidence in the safety managers of the $3-billion British beef industry, symbolized by the March 21,1996 headline in the Daily Express: “Can We Still Trust Them?” (O’Brien, 1996).

The results were speedy. Within days, the European Union imposed ...