eBook - ePub

Daylight Design of Buildings

A Handbook for Architects and Engineers

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

To complement the critical and objective view gleaned from the study of some sixty buildings, this design manual has been developed to provide a more synthetic approach to the principles which lie behind successful daylight design. These principles are illustrated with examples drawn from the case study buildings. The emphasis throughout has been on practical methods to improve design, rather than techniques studied for any intrinsic interest.

The book provides the necessary tools to assist the designer to provide well daylit interiors, and shows that good daylight design is not a restriction on architectural expression but, on the contrary, acts as an inspiration and foundation for good architecture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Daylight Design of Buildings by Nick Baker,Koen Steemers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart 1

The role of light in architecture

1

The role of light in architecture

Bibliothèque National, Paris, by Labrouste, 1859–68.

(James Austin, Cambridge)38

“…Architecture is the masterly, correct and magnificent play of volumes brought together in light…” “The history of architecture is the history of the struggle for light.”

Le Corbusier1

The roles of daylight in architecture are considered from two basic perspectives in this chapter: that of art and science, emotion and quantity, or heavenly and earthly. Historically these roles have been intertwined, but since the age of Enlightenment they have begun to separate and become distinct. In that separation we have lost a holistic understanding of the role of light, but gained knowledge of the science of light. It is through the application of this knowledge to scrutinise the qualities of architectural masterpieces that we can hope to acquire the artistry of lighting design. The purpose of this endeavour is to fulfil both the personal emotional needs – of well-being, comfort and health – and the practical communal needs – of energy conservation – to underpin an environmentally sustainable future.

The understanding and manipulation of light goes to the heart of the architectural enterprise. Vision is the primary sense through which we experience architecture, and light is the medium that reveals space, form, texture and colour to our eyes. “More and more, so it seems to me, light is the beautifier of the building” (Frank Lloyd Wright). More than that, light can be manipulated through design to evoke an emotional response – to heighten sensibilities. Thus architecture and light are intimately bonded.

However, light is not only related to the visual experience of form and space, but is strongly connected to thermal qualities. Light is energy, and whether diffuse or direct, will change to heat when it falls on a surface. This is most noticeable when the light source is intense, as with direct sunlight. The implications of this for the sensorial environmental characteristics of a space are numerous and have a direct impact on air and surface temperatures, as well as indirectly on thermal comfort and air movement. The characteristics of light, heat, air movement and comfort are the key factors in determining a building’s energy consumption, and if manipulated and controlled correctly will minimise reliance on artificial systems.

Thus light in architecture is not of singular concern that can be isolated from other design concerns, but relates to a rich integrated web of interdependent aesthetic and functional criteria.

It is through the critical appreciation of precedents, and the understanding of the science of light, that the art of lighting in architecture can be better instilled in the design process. An investigation of the roles of light through history reveals both the power and beauty of light in architecture. The manipulation of daylight through building designs of our architectural heritage shows the ingenuity of integration and the resolution of the perceived struggle between aesthetic purpose and technical understanding of light.

It is possible to trace the roots of the meaning of light back to early civilisation and before. Through the evolution of man and of society, light is associated with safety, warmth and community. Daylight gave man expansive views over his territory. At night, the flame defined a social focus, allowed man to see in the dark where dangers lurked, and to be protected from the cold. Buckminster Fuller eloquently links sun and fire: “Fire is the sun unwinding from the tree’s log”.2 The strong relationship of light with life is likely to be the reason for its spiritual associations today. This is revealed most powerfully through the religious and ceremonial architecture of past civilisations. However, it is not only in the exclusive context of ‘high’ architecture that an artful skill in daylight design can be witnessed, but also in the more widespread and often functionally led vernacular and ‘primitive’ designs. Put simply, high architecture is concerned with the lighting of the architecture, whereas vernacular buildings are predominantly concerned with bringing daylight in to enable activities to take place –the lighting of a task. Notwithstanding this polarity of purpose, it is frequently the vernacular that produces the spectacular, particularly in terms of the embodied wisdom that is represented.

1.1

Spectacular vernacular

Spectacular vernacular

“Thousands of years of accumulated expertise has led to the development of economic building methods … climatization … and an arrangement of living and working spaces in consonance with their social requirements. This has been accomplished within the context of an architecture that has reached a very high degree of artistic expression.”

Hassan Fathy3

The vernacular tradition has much to teach the modem designer, particularly in response to climatic parameters, notably sunlight with all its visual, thermal, and energy implications. It is also the background against which more monumental architecture is seen and understood (Figure 1.1). Although ‘high’ architecture demonstrates the level of sophistication, power and standing of the elite, traditional design is more closely related to the views and needs of all people, and thus an unselfconscious expression of the society and its culture (Figure 1.2).

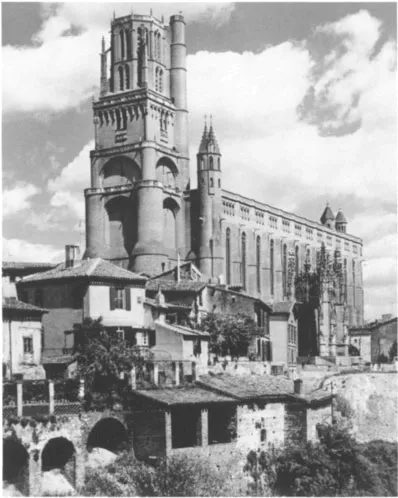

Figure 1.1 The fortified cathedral at Albi, France (begun 1282) seen against the vernacular buildings of the town. (Wim Swaan, London)4

Figure 1.2 Design of traditional structures responding to the needs of climate and culture. Unusual roofscapes, typical of the Sind district in Pakistan, which channel the wind into the building. (Courtesy Atlantis Verlag, Zurich)5

1.1.1 Shade and air

In extreme climates, particularly where the sun’s light and heat are too intense, the vernacular and even primitive builders have turned their hand and initiative to the architectural expressions of solar control.

In warm humid climates primitive dwellings typically consist of a raised open stick construction with a wide over-sailing roof to keep the sun off (Figure 1.3). The open lattice bamboo walls reduce the intense glare of reflected light, limiting visual discomfort, whilst allowing the cooling breeze through to the occupants (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3 A tree house in the village of Buyay, located on Mount Clarence in New Guinea, making the most of the faintest forest breeze.6

Figure 1.4 The simple timber or bamboo envelope, typical of traditional architecture in warm humid climates, reduces glare, diffuse solar gains and provides privacy while allowing good cross-ventilation. A wide overhang provides the primary shading from sunlight (Vernacular Buildings Museum, Hainan Province, South China).

A similar lattice, but made of highly crafted timber, is often seen within the openings in hot arid climates. Called a mashrabiya, the environmental role of the lattice is to soften the light (particularly when made of turned wood – round in section) and allow air flow through whilst maintaining a combination of privacy and a view out. Privacy and view out are the result of the relative intensities of light on either side of the screen, where from the lighter side you see the screen but are unable to see detail through it to the darker interior, thus providing privacy (Figure 1.5). Conversely, from the darker side the screen allows views through to the lighter and more public spaces (Figure 1.6). Furthermore, the size of the interstices between the wood pieces is such as to minimise direct high angle sun penetration, but to transmit some diffuse reflected light perpendicular to the mashrabiya. At eye level the spacing is reduced to limit glare, but higher up the spacing is increased to allow daylight deeper into the space (Figure 1.7). Apart from such screened openings, other less important windows are kept small and set with deep reveals in the thick masonry walls, helping to minimise glare and sunlight penetration.

Figure 1.5 An outside view of a mashrabiya at the As-Suhaymi house in Cairo, showing the privacy of the interior.7

Figure 1.6 View from a mashrabiya. The camera is positioned inside the room but focused on the building across the courtyard, showing the views allowed of more public spaces.8

Figure 1.7 The interior view of the mashrabiya of Figure 1.5. It covers the entire facade of a room in the house and increases ventilation while reducing glare.9

1.1.2 Urban vernacular

The vernacular urban architecture of predominantly hot arid climates, such as Egypt, is characterised by dense courtyard forms, constructed of thick masonry walls with a predominance of small window openings. The proximity of the dwellings to each other ensured that the narrow streets remained sheltered from the intense direct sunlight, and that buildings would provide mutual shade (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8 Plan of part of the village of Baris...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 The role of light in architecture

- Part 2 Daylighting design

- Part 3 Design criteria and data

- Annotated bibliography

- Glossary

- Index