- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Research Design: The Logic of Social Inquiry is a collection of critical writings on different aspects of social research. They have been carefully selected for the variety of approaches they display in relation to three broad styles of research: experimental, survey, and ethnographic. All are classic contributions to the development of methodology and excellent expositions of particular procedures.The book is organized in sections that detail the methods of a typical experimental research program design, data collection, and data analysis. These five sections include The Language of Social Research, Research Design, Data Collection, Measurement, and Data Analysis and Report. Each is preceded by an introduction stressing the unique strengths of the different viewpoints represented and reconciling them in one coherent approach to research.The volume includes displays of philosophical underpinnings of different methodological styles and important issues in research design. Data collection methods, particularly the problem of systematic bias in the data collected, and ways in which researchers may attempt to reduce it, are discussed. There is also a discussion on measurement in which the central issues of reliability, validity, and scale construction are detailed. This kind of synthesis, between such diverse schools of research as the experimentalists and the ethnographers, is of particular concern to social researchers. The book will be of great value to planners and researchers in local government and education departments and to all others engaged in social science or educational research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Research Design by Keith Stribley,Marjo Hoefnagels in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

The language of social research

Introduction

In this section we introduce some of the basic terminology of social research and look at its epistemological foundations. The first reading by Wallace presents a useful model of the scientific process in which most of the key terms appear and introduces some of the principal actors on the research stage; theorist, research director, interviewer, sampling expert, statistician, etc. An important theme is also intro duced: the distinction in the development of theory between ‘discov ery’ and ‘testing’. More of a historical perspective is presented in the next reading, from Von Wright, who usefully outlines the two major traditions of sociological enquiry, positivism, which looks to natural science as the only true model; and idealism of the kind espoused by Max Weber, who emphasized the notion of ‘Verstehen’ or ‘empathic understanding’, as the distinctive feature of the human or social sci ences.

These two traditions lay the foundation for one of the main distinc tions in methodologies that we present in this book, the ethnographic as opposed to the experimental. The exploration is taken a stage further with Popper’s classic discussion in Poverty of Historicism which, in line with the positivist tradition described by Von Wright, argues for the unity of all scientific method. Popper reduces all scien tific reasoning to one basic principle, falsificationism. A scientific proposition is one that is capable of being disproved, and science advances as falsified propositions fall away through rigorous tests, leaving a core of theory which it has not yet been possible to disprove. To Popper the source of such propositions/hypotheses is of little significance; it is the creative element in the process of science which is unanalysable. To those working in the more idealistic or interpretative tradition, however, the source of social science concepts and the hypotheses expressing their relations is of crucial importance; for to them the theories of social phenomena are relatively worthless unless rooted within the meaning systems of the actors to whom they relate. In a rather difficult but powerful article, Alfred Schutz (Reading 4), argues this case, in no way contradicting Popper’s demand for scientific rigour in the development of theory, but parting company with him in his belief that there are no rules to guide the origins of this theory.

Schutz’s position is summed up through his conception of the ‘homun culus’, an idealized type of individual representing a culture/social group, typical with respect to intentions and purposes of the group members, and therefore recognizable to them. It is the job of the social scientist to build his higher level abstractions/explanatory concepts from his conceptions of the interactions of such homunculi, firmly rooted in the culture which they themselves have constructed.

Schutz’s argument is brought down to earth by the introduction, reproduced here, to a lengthy article on methodology by Denzin (Reading 5). Denzin argues for a ‘naturalistic behaviourism’ which, following Schutz’s suggestions, remains firmly based in the concepts of everyday life but uses the full tool-kit of the empirical investigator to develop theory. Unlike many such researchers, Denzin’s concern here is with the origins of theory as well as with the methods by which it is tested. Thus he welcomes the full battery of quantitative or non quantitative techniques which may be appropriate to particular prob lems in the social sciences. As he puts it in a footnote, ‘It is the use to which the method is put and the degree of rigour under which it is employed that determines its usefulness. The quantitatively orientated researcher, then, can also share the naturalistic perspective.’ Denzin’s article seems an appropriate point to begin an examination of writings on the various stages of the social scientific process itself. He brings a refreshing openness of approach to the whole subject, advocating in effect both the rigour, which is the cornerstone of Popper’s arguments, with the grounding of social science theory advocated by Schutz.

Reading 1

An overview of elements in the

scientific process

scientific process

Walter Wallace

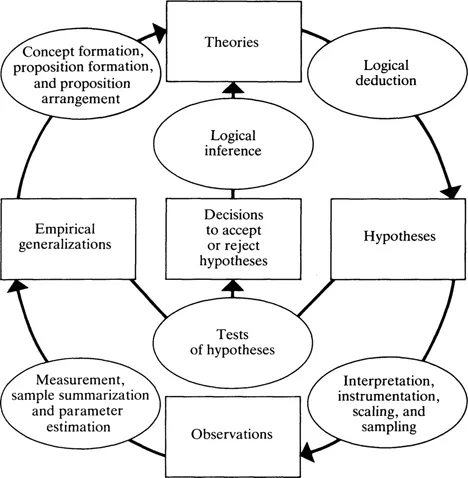

The scientific process may be described as involving five principal information components whose transformations into one another are controlled by six principal sets of methods, in the general manner shown in Fig. 1.1 [. . .] In brief translation, Fig. 1.1 indicates the following ideas:

Individual observations are highly specific and essentially unique items of information whose synthesis into the more general form denoted by empirical generalizations is accomplished by measure ment, sample summarization and parameter estimation. Empirical generalizations, in turn, are items of information that can be syn thesized into a theory via concept formation, proposition formation and proposition arrangement. A theory, the most general type of information, is transformable into new hypotheses through the method of logical deduction. An empirical hypothesis is an informa tion item that becomes transformed into new observations via interpretation of the hypothesis into observables, instrumentation, scaling and sampling. These new observations are transformable into new empirical generalizations (again, via measurement, sample sum marization and parameter estimation), and the hypothesis that occasioned their construction may then be tested for conformity to them. Such tests may result in a new informational outcome: namely, a decision to accept or reject the truth of the tested hypothesis. Finally, it is inferred that the latter gives confirmation, modification or rejection of the theory1.

Before going any further in detailing the meaning of Fig. 1.1 and of the translation above, I must emphasize that the processes described there occur (1) sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly; (2) sometimes with a very high degree of formalization and rigor, sometimes quite informally, unself-consciously and intuitively; (3) sometimes through the interaction of several scientists in distinct roles (of, say, ‘theorist’, ‘research director’, ‘interviewer’, ‘methodologist’, ‘sampling expert’, ‘statistician’, etc.), sometimes through the efforts of a single scientist; and (4) sometimes only in the scientist’s imagination, sometimes in actual fact. In other words, although Fig. 1.1 [is] intended to be [a] systematic rendering of science as a field of socially organized human endeavor, it is not intended to be inflexible. The task I have chosen is to set forth the principal common elements - the themes - on which a very large number of variations can be, and are, developed by different scientists. It is not my principal aim here to analyze these many possible and actual variations; I wish only to state their underlying themes. Still, it seems useful to discuss briefly the types of variation mentioned above (particularly the last type), if only to defend the claim that my analysis of themes is flexible enough to incorporate, by implication, the analysis of variations as well.

Fig. 1.1 The principal informational components (rectangles), methodological controls (ovals) and information transformations (arrows) of the scientific process.

Each scientific subprocess (for example, that of transforming one information component into another, and that of applying a given methodological control) almost always involves a series of preliminary trials. Sometimes these trials are wholly imaginary; that is, the scientist manipulates images in his mind of objects not present to his senses. He may think, ‘If I had this sort of instrument, then these observations might be obtained; these generalizations and this theory and this hypothesis might be generated, etc.’; or perhaps, ‘If I had a different theory, then I might entertain a different hypothesis - one that would conform better to existing empirical generalizations.’ When these imaginary trials, sometimes running several times through the entire sequence of scientific transformations, seem to be accomplished all in one instant (and when, of course, these imaginary trials turn out, when actualized, to be correct and fruitful), the scientist’s performance is said to be ‘insightful’. It is here, in making imaginary trials, that ‘intuition’, ‘intelligent speculation,’ and ‘heuristic devices’ find their special usefulness in science.

For maximum social acceptance as statements of truth by the scien tific community, trials must not be left to imagination alone; they must become actual fact. The actualization of scientific processes (for example, actually constructing a desired instrument) usually brings about a reduction in speed and an increase in the rigor and formaliza tion with which trials are carried out, because it subjects the entire trial process to the constraints and intransigences of the material world. An increase in the role specialization of the scientists who carry out the trials is also likely to result.

It is important to note that in the trial process just referred to (whether imaginary or actualized), directions of influence opposite to those shown in Fig. 1.1 are often taken temporarily2. For example, the first formulation of a hypothesis deduced from a theory may be ambiguous, imprecise, logically faulty, untestable or otherwise unsatis factory, and it may undergo several revisions before a satisfactory formulation is constructed. In this process, not only will the deduced hypothesis change, but the originating theory may also be modified as the implications of each trial formulation reveal more about the theory itself.

Similarly (to move further around Fig. 1.1), the process of trans forming a hypothesis into observations may involve several interpreta tion trials, several scaling trials (in which new scales may be invented and alternative scales selected) and several sampling trials. In each trial (at this point in the scientific process, trials are often called ‘pretests’ or ‘pilot studies’), new observations are at least imagined and often actually made; and from them the investigator judges not only how relevant to his hypothesis the final observations and empirical generalizations are likely to be, but how appropriate his hypothesis is, given the observations and generalizations he can make. He may also judge how appropriate his methods are, given the information he is seeking to transform. Thus, the invention and trial of a new scaling, or instrumentation, or sampling, or interpretation technique may result in the deduction of new hypotheses rather than the reverse process shown in Fig. 1.1.

Despite these retrograde effects that may be seen for every.informa tion transformation indicated in Fig. 1.1, the dominant processual directions remain as shown there. When counterdirections are taken, they are best described as background preparations and repairs prior to a new advance. Thus, the invention of a new instrument for taking observations may occasion the deduction of new hypotheses, so that when new observations are actually and formally taken with the new instrument, they will be scientifically interpretable (that is, transform able into empirical generalizations that will be comparable with hypotheses, etc.) rather than mere extra-scientific curiosities. Simi larly, a particular formulation of a theoretically-deduced hypothesis may react on its parent theory or on the method of logical deduction, and the theory may react on its supporting empirical generalizations, decisions and on the rules of logical induction; so that when the next step is actually taken (that is, when observations are made, via interpretation of the hypothesis, scaling, instrumentation and sam pling), it will rest on newly-examined and firm ground.

But as C. Wright Mills implied, such careful background preparation does not always occur, and in practice any element in the scientific process may vary widely in the degree of its formalization and integra tion with other elements. Mills argued specifically that the relationship of theorizing to other phases in the scientific process can be so tenuous that theory becomes distorted and enslaved by ‘the fetishism of the Concept’. Similarly, he claimed, the relationship of research methods to hypotheses, observations and empirical generalizations can be so rigid that empirical research becomes distorted by ‘the methodological inhibition’.3 It may be added that the distinction between researches that ‘explore’ given phenomena and researches that ‘test’ specific hypotheses is another manifestation of the same variability in degree of formalization and integration; ‘exploratory’ studies, precisely because they probe new substantive or methodological areas, may rest on still unformalized and unintegrated theoretical, hypothetical and methodological arguments. Understanding a published report of such a study often depends on inferring the theory that ‘must have’ under girded the study, or on guessing the empirical generalizations, or hypotheses, or observations, or tests, etc., that the researcher ‘must have’ had in mind. ‘Hypothesis-testing’ studies, however, are likely to have more explicit, more formalized and more thoroughly integrated foundations in all elements of the scientific process.4

Finally, in this description of elements in the scientific process, it seems useful to note that sociologists (and other scientists, as well) often refer simply to ‘theory’ (or ‘theory construction’) and ‘empirical research’ as the two major constituents of science. What is the relation of these familiar terms to the more detailed elements just outlined?

Fig. 1.2 is designed to answer this question by suggesting that the left half of Fig. 1.2 represents what seems to be m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- General Introduction

- Section 1. The language of social research

- Section 2. Research design

- Section 3. Data collection

- Section 4. Measurement

- Section 5. Data analysis and report

- Index