- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing Sustainable Development

About this book

In a world where environmental problems spill across political, administrative and disciplinary boundaries, there is a pressing need for a clear understanding of the kinds of organizations, management structures and policy-making approaches required to bring about socially equitable and ecologically sustainable development. In this second edition, the authors incorporate lessons from a decade of work on the conditions of sustainability in both developed and developing countries. They prescribe action networks - partnerships of flexible, achievement-oriented actors - and present new case studies demonstrating the success of organizations that have applied this approach. They also introduce case studies on action networks that work simultaneously on international, national and local levels.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Introduction

1

The Ecology of an Industrial Planet

… there is no ‘natural habitat’, in the sense of a terrestrial ecosystem that has evolved without the presence of a human element. There is only the choice between different methods and forms of human involvement in the habitat.T Swanson and E Barbier1

In the life of the earth, 200 years is a mere flicker of time. Yet within the past two centuries the rise of industrialism has transformed the planet in ways that natural processes and previous civilizations would have taken millennia to achieve. In this short era of ‘modernity’ we have wrought dramatic changes to the environment, the most far-reaching being our effect on the chemistry of the atmosphere and the genetic diversity of the planet. These changes have given rise to fear of a global environmental crisis, and to calls for a shift from exploitative industrialism – ‘business-as-usual’ – to something called ‘sustainable’ development.

In Chapter 2 we consider what kind of development can be defined as sustainable. Here, we review the global social trends and negative environmental consequences that are likely to lead to unsustainable development in the next half century. These constitute the first of a series of constraints on sustainable development that are explored in this book.

This chapter can do no more than provide a brief overview of global environmental issues: many comprehensive sources are available.2 Our purpose is to explore the scale of major challenges to sustainable development, to give some idea of their interactions and to set the stage for discussion about how we might improve environmental management. This book is about the processes of environmental decision-making and implementation, the assumptions and values that underlie these processes, and how they can be improved to lead to sustainable development.

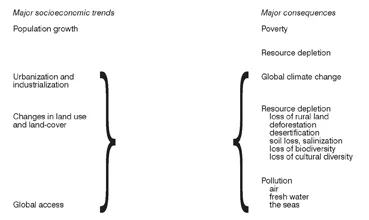

Figure 1.1 outlines some major world trends and their consequences. The trends are not necessarily malign in themselves, whereas the consequences we have listed always are. So, for example, we do not immediately interpret as negative population increase, industrialization, the growth of cities, the shift of land from forestry to agriculture, or the increased mobility offered by the automobile or global air transport. Population growth can be accommodated easily in some ecosystems; many countries need industrialization to alleviate poverty; for many people an urban life-style is preferable to the limitations of rural life; almost everybody wishes to travel; and so on. On the face of it, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with these facts and aspirations.

The key issue for sustainable development is the magnitude of the changes induced by the trends listed above. There is a ‘technocentric’ school of thought which suggests that the negative consequences of these trends can be overcome or managed; and that human technological prowess will allow indefinite economic growth, will help to manage and eventually contain global population increase, and will deliver ever higher living standards.3

However, this perspective fails to take sufficient account of the delicate balance of complex ecosystems and the possibility of dynamic negative changes being triggered by excessive human growth. For example:

• The current world population growth of some 80 million people per year – although down from the peak of 87 million in 1990 – virtually ensures poverty, undernourishment and resource depletion in many ecosystems.

• Industrialism on the current fossil-fuel burning model is unsustainable in atmospheric terms.

• A certain amount of rapid urbanization is manageable, but not with the growth rates seen in cities such as Lagos, which grew by 10.2 million people in 1975–2000 at an average annual rate of 5.8 per cent.4

• The 501 million cars in use worldwide are not only precipitating local crises of congestion and pollution, but adding to wider problems of environmental impact: the billion-strong fleet forecast for 2020 will contribute greatly to global pollution problems as well as to a growth in traffic across the world of some 60 per cent in the period 2000–2020.

• Deforestation and carbon dioxide generation on a massive scale are eroding the earth’s built-in adjustment mechanisms in many areas.

• Our use of global fresh water and marine resources has grown hugely: freshwater withdrawals have nearly doubled since 1960, such that humanity uses more than half the planet’s accessible freshwater run-off – great rivers such as the Colorado and the Yellow River now fail to reach the sea much of the time as so much water is diverted for agriculture and industry; marine fish consumption doubled between 1960 and the early 1990s, such that some 60 per cent of the world’s sea fish resources are overfished or at the limit of sustainable harvesting.5

Similarly, at the local level, the scale of new development is tipping many economies and ecosystems into crisis. A small number of tourists on a Greek or a Caribbean island can be a boon to local life and even provide an economic basis for sustainable development. But when tourists outnumber local people by ten to one, and foreign travel companies package both local economy and local culture for sale, a threshold has been exceeded and negative effects begin to pile up for all concerned. In every case, the magnitude of change is too great. Critical, if unknown, thresholds have been exceeded and the situation is no longer amenable to beneficial local management. Usually, thresholds for sustainability – carrying capacities – are substantially exceeded even before we become aware of the nature of the problem.

The situation is made more complex and intractable because the trends and their consequences are highly interactive in a manner that is difficult to identify and measure, and sometimes even difficult to imagine. So, for example, urbanization is partly a result of, and partly a cause of, migration from countryside to city. The urbanization process itself generates economic activities which raise income levels, draw in resources from the countryside and even from faraway savannahs and rainforests, and generate enormous amounts of waste which end up as pollution of air, water and land. The increased income generates more consumption, more industry, more pollution, more automobility, urban sprawl, endemic traffic congestion, and so on. Urban sprawl results in the loss of prime farmland which, when combined with rural population growth, contributes to lowland forest loss due to agricultural expansion in the countryside well away from the city, thus completing a cycle of interaction. These processes are unfolding rapidly, but our responses to date fail to match the size of the problem.

Relationships between such trends and their consequences are not merely distinctions on a continuum of ‘good’ to ‘bad’ environmental effects: they are the very stuff of debate over the nature of sustainable development and the future of the planet. They go to the heart of our values and assumptions about how much of the earth’s finite resources we are individually entitled to consume, and to our views on how much resource depletion is allowable in a sustainable framework. They are also important because there has been little public debate about the meaning of sustainable development. It is perhaps most important to acknowledge that, given the political and economic constraints on environmental policy, progress towards sustainability will have to be incremental rather than revolutionary. This means that the best time to start doing something, and then to learn from what we are doing, is now.

The Major Trends and Consequences

Population growth and poverty

Between 1850 and 1950 the world’s population doubled from 1.25 billion to some 2.5 billion. By 1987 it had doubled again. A further billion people were added in the following decade. The global population at the turn of the millennium is 6 billion: in June 1999 the United Nations (UN) forecast that the 6 billionth person was due to be born in October 1999. Estimates for the next 100 years range from a total population of 8 to 14 billion before the rise levels off and some time in the 22nd or 23rd century stabilization or a fall occurs. We can hope that the stabilization will be a result of more countries passing through a ‘demographic transition’ in which average family size falls as agricultural productivity rises, contraception becomes more available and culturally acceptable, women gain better access to education and enter the labour market in larger numbers, and urban populations rise. But rising mortality rates could also play a part, reflecting the spread of diseases such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), extreme weather from climate change and pollution-related illness.

Source: Mannion, A M, Global Environmental Change: A Natural and Cultural Environmental History, Longman Scientific and Technical, London, 1991

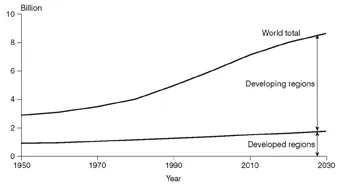

This rapidly rising population reflects progress in the form of increased life expectancy and improved health care. It also means that more skills, ideas and labour are available to add to economic and social resources: more people are not intrinsically a ‘burden’ on families or societies, and having children makes sense to people everywhere. But although warnings about the ‘population explosion’ are out of fashion, there can be no doubt that the high rates of increase in population in many areas mean a significant increase in pressure on the earth’s resources and food-producing systems. In some industrialized countries population is set to stabilize or decline, but in parts of the developing world, which accounts for the majority of the global population (Figure 1.2), big increases are yet to come: some countries will double or triple their population by 2050 on current trends (Table 1.1). By 2050 the population of Nigeria will have risen from 122 million in 1998 to 339 million – more than the total African continent supported in 1950.6 In the same period, the population of India is predicted to surpass China as the most populous country, adding 600 million people to reach over 1.5 billion.

Approximately one-fifth of the world’s population (about 1 billio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Part I – Introduction

- Part II – The Western View of Humankind and Nature

- Part III – Global Integration and Local Democracy

- Part IV – Innovative Management for Sustainable Development

- Part V – Case Studies in Innovation Management

- Notes and references

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Managing Sustainable Development by Michael Carley,Ian Christie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.