1 Mimicry in Mynas (Gracula Religiosa): A Test of Mowrer’s Theory

Brian M. Foss

Mowrer (1950, chap. 24) states that sounds must be associated with reinforcement for talking birds to imitate them. In his most recent formulation (Mowrer, 1960) the reasoning is as follows: if any stimulus, for instance the sight of a human being, is repeatedly associated with a primary reinforcer (e.g., food) then the appearance of the human will give rise to “hope,” which in turn is reinforcing; if the human repeatedly utters a given sound, that sound will also produce hope; if now the bird, in the course of its babbling, makes noises which approximate those produced by the human, these will produce hope, and the production of the noises will be reinforced—the more so the more the noises approach the human version.

Skinner (1957, p. 64) appears to accept this view, although he is not primarily concerned with factors affecting the first appearance of any response. He is concerned with the control of the response once it has appeared, and this has been shown to be possible with the utterances of mynas (Grosslight, Harrison, & Weiser, 1962).

Mowrer believes that imitation learning by talking birds can be taken as a model for other kinds of imitation. A child will tend to imitate noises of adults, especially those with whom he is identified, since they will have the greater reinforcing power. Obviously the exact mechanism of learning will be more complicated in cases other than learning to produce sounds. For sounds, the child can match his own utterances against those produced by the person being imitated, but it is not clear how this matching can happen when for example a movement is being imitated.

Some doubt is felt about Mowrer’s theory for two reasons: (i) talking birds often pick up noises which are not consistently associated with reinforcement (e.g., the noise of a dripping tap); (ii) bird fanciers often recommend training birds to talk with the cage covered, and also by means of gramophone records (see, for example, Pet Myna, 1957), situations which seem to minimize the chances of hope, in Mowrer’s sense.

The present experiment attempts a rough test of the theory that learning to utter a sound depends on the sound’s being associated with reinforcement.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were two groups of Indian Hill Mynas (Gracula Religiosa Intermedia) bought as “gapers” and aged about 8 months at the start of the experiment. Group A consisted of two birds and group B of four. This difference in numbers was incidental to the experiment. Since these birds learn from each other, in a sense the experiment was done on two subjects. The two groups were treated slightly differently: group A were kept in a cage in the experimenter’s room; group B were all in one cage in a room adjoining another which could be reached by the experimenter without the birds seeing or hearing him.

Procedure

The stimuli used were an ascending whistle (X), going from 500 c.p.s. to 2000 c.p.s., in the space of 2 sec, and the same whistle reversed, and therefore descending (Y). Each whistle was recorded on a loop of tape which repeated the whistle every 61/2 seconds. This kind of whistle is not heard in the repertoire of an unsophisticated bird and its timbre was also unusual. This choice was made to help in identifying the whistles when the brids finally produced them, and also to minimize transfer. A whistling ban was imposed in the neighborhood of the cages.

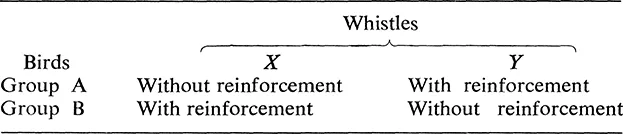

The birds were trained as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Training Schedule

This design did not allow for controlling which whistle was heard first for each group. To give Mowrer’s theory priority, each group heard first the whistle associated with reinforcement, the number of repetitions of each whistle being gradually increased from 10 to 30 per session. The whistles associated with reinforcement were always played at midday, the others at dusk (Table 1.2).

At the midday sessions food was prepared in full view of the birds, and put in the cages (always by the same experimenter)

while the appropriate whistle was being played. At the dusk sessions the groups were treated differently. Group A lives in a room where they saw many people and heard a good deal of conversation. Their cage was covered at least 15 minutes before the tape was played and remained covered for at least 30 minutes afterwards. During this period they heard no human vocal noises. For group B, living in an isolated room, the tape was switched on in an adjoining room, so that the birds neither heard nor saw a human during the session.

Table 1.2 Numbers of Repetitions of Stimuli per Session

| Midday | Dusk |

| (reinforcement) | (no reinforcement) |

| Day 1 | 10 | 10 |

| Day 2 | 20 | 20 |

| Day 3 onwards | 30 | 30 |

Recording Results

After 5 weeks (less 2 weekends) of this daily procedure, the procedure was stopped and recordings were made of each group, with and without the experimenter in the room. For group A a total of 12 hr. was sampled, for group B 9 hr., both spread over 3 days. The recordings were made at various times between 930 a.m. and dusk.

Results

The birds tended to incorporate the test whistles into other whistling and babbling, and later (after the experiment was over) tended to construct variations on the original themes. However it was possible to count those whistles which were produced in isolation from other utterances, and which clearly had the correct timbre and the correct ascending or descending character. (The birds were successful in reproducing the whistles over only about half of the range of the test stimuli.) The results are shown in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3 Numbers of Whistles Reproduced over the Times Sampled

| Whistle associated with reinforcement | Whistle not associated with reinforcement |

| Group A | 26 | 21 |

| Group B | 11 | 13 |

It is clear that both groups had learned both whistles. There was no tendency for one whistle rather than the other to be produced at any particular time of day. Group A produced whistles equally often while the experimenter was in and out of the room; group B never produced the whistles while the experimenter was near during the period under consideration. They did so for the first time several days after the experiment was finished.

Other Findings

It was not until recordings were made in group B’s room in the absence of humans that it was discovered that these birds had acquired a repertoire of words, as well as the intended whistles. The tendency for mimicked noises to be produced at first when humans are not present had been observed with a previous collection of birds, and has also been reported by Thorpe (1961, p. 119). Recording of group A was not begun early enough to discover if they behaved similarly.

Both groups produced a great amount of babbling (group B almost entirely when no humans were present) which contained the phonemes of human speech but no words. From a distance it was indistinguishable from human conversation. This behavior is reminiscent of human prelingual babbling which is said to become restricted gradually to the phonemes of the adult language (Brown, 1958, pp. 199–200).

Babbling, and also native noises (shrieks and “grackle” noises), were set going by various stimuli—human conversation, the telephone ringing, doors banging. After the end of the experiment (this applies particularly to group B), if the test whistles were played, the birds frequently joined in, on occasion joining the whistle half way through its course and finishing it. This was done exactly on pitch, as far as can be detected,

Discussion

The experiment showed that reinforcement did not play a part in determining which sounds the mynas would imitate. It might be argued that during the “reinforced” sessions the birds were distracted by the sight and anticipation of food, whereas...