![]()

Familiar to millions as the gateway to Britain, the White Cliffs of Dover have a deeper environmental significance as storehouses of earlier atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Earth without humanity

Over the last two decades, scientific debate about life on other planets has recognised that something we usually take for granted is in fact remark-able. This is that conditions on Earth are ‘just right’ for living things. This is all the more surprising when we compare the Earth with Mars and Venus. All three planets are formed from the same materials and started with atmospheres consisting largely of carbon dioxide. Today Mars has virtually no atmosphere, so temperatures on the surface fluctuate enormously between day and night and average - 60 °C. Venus, on the contrary, has a very dense atmosphere of carbon dioxide and surface temperatures average 460 °C. By contrast, large areas of the Earth’s surface have fairly equable temperature regimes as well as moderate variations in wind and water availability. Just as Goldilocks found some things in the three bears’ cottage too hot or too cold, too hard or too soft, but others ‘just right’. so the Earth is remarkably well suited to complex life forms. The key to these conditions is the nature of the Earth’s atmosphere, because without it surface tem-peratures would, like the moon, average -18 °C.

When we look at the Earth’s atmosphere and ask how it happens to be ‘just right’ for life, we find that the mystery deepens. Geologists have been able to show that the present atmosphere is completely different from the atmosphere which existed in the early part of the Earth’s history.

Geologists now believe that the Earth formed by the accretion of particles of matter about 4,600 million years ago. Gravitational attraction progressively forced these particles together and raised their temperature until they solidified and even melted, generating volcanic processes. Massive quantities of carbon dioxide and water were emitted by volcanoes. They were held by the Earth’s gravity to form its first atmosphere and ocean. Then, as now, carbon dioxide allowed solar radiation to pass through to the surface but absorbed radiation from the surface and slowed its escape to space, so atmospheric temperatures climbed to about 28 °C. But an atmosphere of carbon dioxide would be inhospitable to all known plants and animals. How has it been transformed into its present state, with 79 per cent nitrogen, 21 per cent oxygen and small traces of carbon dioxide, water vapour and rare gases?

Cloud patterns both indicate atmospheric circulation and intercept incoming solar radiation.

The changes to the atmosphere can be reconstructed by geologists because the rock deposits of a particular period relate to the chemical content of the atmosphere. About 3,500 million years ago, extensive layers of ‘banded ironstones’ were laid down, containing iron compounds which could only exist in an oxygen-free atmosphere. One thousand million years later, mats of blue-green algae had appeared and were carrying out one of the crucial processes of life - photosynthesis. In photosynthesis, the energy from the sun is used by green plants to combine carbon dioxide and water into sugars, and oxygen is given off. Once the blue-green algae had liberated some oxygen into the air, microscopic marine plants (called phytoplankton) came into existence, strengthening fixation of carbon through photosynthesis. Some of these plants, and hence this carbon, were locked away in sediments in the deep ocean. By 2,000 million years ago there was enough oxygen in the atmosphere to prevent the formation of banded ironstones: iron-rich rocks were now ‘red beds’. coloured by iron compounds similar to those in rust.

During the ensuing 1,000 million years a new form of carbon fixation was added: some animals and plants began forming limestone skeletons or shells. Under the right conditions, these were deposited in shallow seas as chalk or limestone. In the process, the oxygen content of the atmosphere increased progressively until land plants and animals could become established. About 300 million years ago there was a major period of coal formation: this was another way in which carbon in plant remains was made unavailable to the oxygen in the atmosphere. Very recently (in geological terms) humans have discovered that, just as plants and animals combine carbon compounds with oxygen in the process of respiration and so generate energy, so coal can be burned in air to give off heat, releasing carbon dioxide. Before this technical breakthrough, the balance between photosynthesis and respiration had removed almost all carbon from the atmosphere and increased oxygen content to its practical limit. If oxygen was any more plentiful, there would be a more serious danger of plant remains bursting into flame spontaneously. However, the combination of oxygen with ammonia released from volcanoes produced nitrogen and water, and the stable nature of nitrogen moderates the reactivity of air.

To sum up: over thousands of millions of years blue-green algae and plants have removed carbon from the atmosphere. The presence of deep oceans, shallow seas and swamps has provided a variety of ways for this carbon to be locked away from oxygen. In the process, the atmosphere has become cooler as the proportion of carbon dioxide decreased, and large quantities of oxygen have been released into the atmosphere where it is available for respiration and combustion. The ‘just right’ conditions for complex life forms have actually been created by simpler forms of life. As living things have evolved into more complex forms, the environment has evolved in parallel and the actual adjustment of living things and inanimate materials and processes is more than coincidental.

But the balance between atmosphere and life is not static. Change one and the other must respond. So the dramatic changes in animal and plant life brought about by population and economic growth are bound to change the atmosphere, and hence other related systems. Several of these systems are crucial to natural vegetation and agriculture, so the next step is to sketch the carbon and water cycles and to recognise the vital role of solar radiation as the driving energy source of all these natural systems.

The carbon cycle

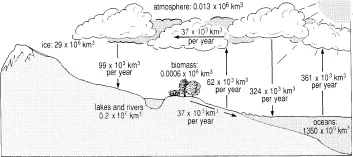

As described above, past processes have taken huge quantities of carbon from the atmosphere and locked it into geological reservoirs. The estimated amounts are shown in Figure 1.1. In fact ‘locked’ is too strong a word as there are major flows between reservoirs. Most of these are natural, but in recent decades society has added to them.

The natural processes would be in balance in the short term. Carbon dioxide is taken from the atmosphere by photosynthesis and by dissolution in the oceans. Carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere by the respiration of organisms on land and, via sea water, in the oceans. Some plant and animal remains are locked into peat bogs or ocean sediments and so not returned to the atmosphere. Limestone and corals are still forming, locking calcium carbonate away - but carbon dioxide is still being released from rocks through volcanic activity. The size of the different reservoirs and the rate of flow between them are very different and the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is minute compared with the amounts to be found elsewhere.

Figure 1.1 The carbon cycle, showing major reservoirs and flows with quantities in thousand million tonnes. Nat all the flows can be measured, but of those which can (e) is the largest at 70 × 109 tonnes per year. Only part of (b) is known: marine organisms absorb abaut 45 × 109 tonnes per year, but the ocean itself may dissolve much more than this.

A newly significant input of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere is that released by the combustion of fossil fuels. At 5,000 million (i.e. 5 × 109) tonnes per year, this is small compared to the natural flows, but it is 0.7 per cent of the amount in the atmosphere, so it could increase atmospheric concentration substantially in a few decades if the other flows fail to adjust. Observations over the last few decades suggest that about half of this extra carbon dioxide is absorbed in ways not yet identified, but that the concen-tration in the atmosphere has risen from 315 parts per million (p.p.m.) in 1957 to 350 p.p.m. in 1987. In comparison to this, air trapped in ice sheets over the last 160,000 years has varied between 180 and 300 p.p.m. So the current level is higher than in recent geological history, and on current trends it could be 600 p.p.m. by the end of the next century. The effects of this will be discussed in Chapter 8.

The Water Cycle

Everyone knows that rain falls from the clouds and that some reaches rivers which flow to the sea. Anyone living in Britain can see that the clouds bring most rain when they come in from the Atlantic. A moment’s reflection suggests that the clouds obtain their moisture from evaporation from the sea. There is in fact a cycle in which water moves from the sea to the air, on to land and back to the sea. Scientists have made estimates of the amounts of water present on land, in the sea and in the air and of the annual rates of flow between them. These are shown in Figure 1.2.

A crucial feature of this cycle is that most water is in the oceans and very little in the atmosphere. Comparing the rates of flow into and out of the atmosphere with the average amount present, it appears that a particular droplet of water only remains in the atmosphere a week or two before falling as rain or snow. Conversely, a drop of water falling into the sea remains, on average, for 4,000 years. This makes the atmosphere very variable and sensitive to inputs and outputs.

Of course, the figures given are averaged over the whole globe over a year and this conceals great differences between areas and over time. The tropics and hilly areas exposed to mid-latitude westerly winds may receive several hundred centimetres of rain a year while deserts and polar areas may receive only 10 or 20 centimetres of rain or its equivalent in snow. The availability of rain seriously affects plant growth, but plants also have the effect of increasing amounts of water entering the atmosphere. As well as evaporating from the surface, some water is taken up by plants and transpired through leaf pores into the air. The total amount of water returning to the air as water vapour, a process called evapotranspiration, may be much greater than the amount evaporated. In turn, greater humidity encourages more rain and more plant growth, so yet again natural systems show complex self-organisations.

But it’s not enough just to admire the elegance of natural cycles. We also need to ask ‘what makes them go?’.

The water cycle concentrates solar energy in a way which allows non-polluting and sustainable power generation.

Figure 1.2 The water cycle. Quantities in each reservoir are given in million cubic kilometres (106 km3) and flows, indicated by arrows, in thousand cubic kilometres (103 km3).

Powering the cycles

Like a pedal cycle, natural cycles such as those of water and carbon require an outside source of energy. It’s no great surprise that their source of energy is the Sun, but this in fact identifies a basic principle: the energy in environmental processes flows continuously, arriving from and being lost to space, while matter is present in constant amounts and can only be transformed between different states. The flows of energy are exceedingly complex and include the temporary storage of solar energy in the form of fossil fuels, but only a small fraction of the energy that reaches the Earth is stored in this way. What happens to the rest?

The broad pattern of energy throughput is shown in Figure 1.3. Almost one-third of the solar energy which reaches the atmosphere is reflected back into space by dust and clouds. About one-fifth is absorbed by the atmosphere before reaching the surface; just under half reaches the land or sea surface, of which a quarter is reflected straight back to space, half powers the evaporation of water vapour from land and sea and the remainder is reradiated and absorbed by the atmosphere, warming it and causing vertical circulation; somewhat less than one per cent drives the wind and currents and a mere 0.2 per cent is used in photosynthesis. The enormous quantity of solar energy in the atmosphere is demonstrated by the fact that even the tiny proportion used in photosynthesis is 30 or so times as much as the amount of energy used by human society.

Figure 1.3 What happens to the Sun’s energy in the atmosphere?

Of course, in practice the amounts of solar radiation reaching the surface of the Earth vary greatly, depending on the angle of incidence and on cloud and dust cover. Because the Earth’s axis is inclined towards the Sun, the apparent direction of the Sun varies from 231/2 °N in July to 231/2 °S in January and polar areas receive a substantial amount of radiation in summer. This is one way that temperature is raised at the poles. Another way is that atmospheric and ocean circulation combine to transfer heat from equatorial regions towards the poles. This transfer is associated with distinctive pressure, wind and precipitation regimes in particular areas.

A world without Homo sapiens

Before we move on to analyse human impacts on natural environments, it will be ...