- 801 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

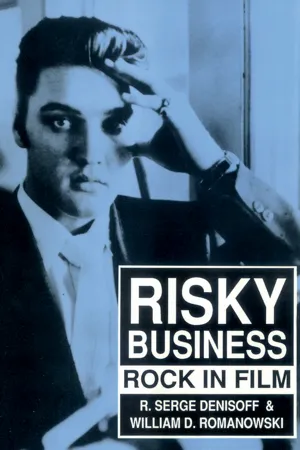

The role of motion pictures in the popularity of rock music became increasingly significant in the latter twentieth century. Rock music and its interaction with film is the subject of this significant book that re-examines and extends Serge Denisoff's pioneering observations of this relationship.Prior to Saturday Night Fever rock music had a limited role in the motion picture business. That movie's success, and the success of its soundtrack, began to change the silver screen. In 1983, with Flashdance, the situation drastically evolved and by 1984, ten soundtracks, many in the pop/rock genre, were certified platinum. Choosing which rock scores to discuss in this book was a challenging task. The authors made selections from seminal films such as The Graduate, Easy Rider, American Grafitti, Saturday Night Fever, Help!, and Dirty Dancing. However, many productions of the period are significant not because of their success, but because of their box office and record store failures.Risky Business chronicles the interaction of two major mediums of mass culture in the latter twentieth century. This book is essential for those interested in communications, popular culture, and social change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Risky Business by William D. Romanowski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Rock Around the Clock: The Changing of Popular Music

In twenty years, when Junior has grown into a sedate married man, father and pillar of the community, he will remember “Ko Ko Mo” wistfully and be distressed no end by the songs his son admires. Only Tin Pan Alley will stay young with each new generation.

—Mitch Miller, Columbia Records executive

It’s gotta be rock ’n’ roll music if you wanna dance with me.

—Chuck Berry, artist

. . . in the theatre, watching Blackboard Jungle, they couldn’t tell you to turn it down. I didn’t care if Bill Haley was white or sincere . . . he was playing the Teen-Age National Anthem and it was so LOUD I was jumping up and down. Blackboard Jungle, not even considering the story line (which had the old people winning in the end), represented a strange sort of “endorsement” of the teen-age cause: “They have made a movie about us, therefore, we exist.”

—Frank Zappa, artist

The Fifties were a strange confluence of C. Wright Mills’s Age of Somnabulism and Garry Marshall’s Happy Days, mixed with technology seemingly run rampant. The decade was neither as tranquil as the ageless adolescent—Marshall—would portray nor as unconscious as the social gadfly Mills—the author of Power Elite (1956)—indicated. The fly in the ointment was technology. In the form of audio/visual communications, drastically altered media would interactively reshape the world of adolescents.

With a fatherly war hero in the White House, the nation appeared fairly stable despite the Korean “police action” and the McCarthy “red scare.” Appearances, as always, would prove deceiving.

Demographically and technologically, significant changes were taking place. The postwar birth rate augured ramifications for the social fabric.

The slumbering behemoth, television, was coming into its own. In 1952 one-third of American households were plugged into the tube, and the number continued to increase. The televisual home invader dichotomized life-styles and values along generational lines. The film industry was forced to redefine itself. Its massified notion of “family entertainment” was washed away by Ed Sullivan, Milton Berle, and Howdy Doody. New marketing, production, and distribution strategies became imperative. Old habits and notions, however, wither slowly.

The record industry, similarly, was being affected. The labels were run by an elite of A&R men (Mitch Miller, Ken Nelson and others) as powerful as the Meyers, Goldwyns, Cohns, and Warners had been in the 1930s. Their stable of swing-era remnants, however talented, lacked the universal appeal of earlier decades. Technology would accentuate the generational cleavage with the infamous “battle of the speeds.”

At a 21 June 1948 press conference, Columbia Records (a division of CBS) president Edward Wallerstein introduced a “revolutionary new product” called the LP (long-playing) record. One side could play twenty-three minutes without interruption. The audio quality was excellent. Media people at the Waldorf-Astoria press gathering claimed the LP’s sound quality surpassed that of the 78. RCA Victor, CBS’s major competitor, was aware of the innovation but remained silent. CBS offered to share its engineering expertise with all of the labels; RCA’s reticence, however, found Columbia with the only major-label 33⅓ product. The monopoly allowed the label to rack up 1.25 million in sales by the end of 1948.

The LP rapidly became a middle-class toy for upscale consumers. The new modality, according to inventor Peter Goldmark, was especially conducive to symphonic and operatic music. Jazz, unsuited to the confines of the 78, was showcased. Broadway musicals and “mood music” were strong sellers. All of these genres were aimed at adults.

RCA broke its silence in 1949 with the introduction of yet a third speed: 45 revolutions per minute (rpm). As with the LP, new hardware would accompany the seven-inch, vinylite disc. RCA advertised the product as having “the world’s fastest changer.” The sound and time quality of RCA’s entry was akin to that of the now-doomed 78. Saturday Review wisely noted that RCA had limited “itself to the convenience of one segment of the record public (the large mass market) and left the smaller, if more discriminating, public.” The medium shortly would become the message.

The immediate public reaction was bewilderment. The industry itself, according to Schicke, “was utterly flabbergasted when the word of the third speed spread”;1 RCA’s short-sighted decision to introduce a competing speed is best explained by the long-standing rivalry between the two recording giants. Gelatt describes consumer reaction to the myopic war of the speeds: “The postwar record boom had been turned into a bust.” Retail sales dropped from a peak of $204 million in 1947 to less than $158 million the year RCA unveiled the short-playing record. Executive intransigence continued. CBS won the hearts and minds of adult record buyers in the speciality areas. Losing millions of dollars and faced with potential artist defections, RCA was reluctantly moving toward the LP.

“RCA would have probably continued to sustain financial losses to keep the fight alive, were it not for the fact that a number of Victor’s most important artists threatened to quit”2 wrote an observer. Upon hearing Bruno Walter on a CBS disc, the renowned conductor Arturo Toscanini became one of the discontented RCA artists.

The down side of the turntable detente was class and generational fragmentation. The LP until the Beatles, was a costly, upscale item—the product and hardware were aimed at adults.

Only a small number of rock ’n’ rollers were deemed sufficiently commercially attractive to make albums. Elvis Presley’s Love Me Tender soundtrack was released on a 45-rpm, extended-play disc (EP). The seven-inch EP, with four selections, priced at $1.49, was aimed at teens (c.1955, LPs listed at $3.98 and 45 singles were priced at $.89).

The lower-cost singles became the currency of the Top 40, rhythm and blues (R & B), and country consumers. Off the record, label executives would curse the high-profile, low-profit product. One executive said, “You know, the camel is a horse designed by a record company president.”

CBS appeared to win the technology battle while losing the short-term market war. Radio stations that were tied to trade charts preferred cuing a one-song disc. Program directors felt AM hit-parade listeners were singles oriented, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Price-conscious buyers preferred the seven-inch disc. The key, however, proved to be the jukebox operators and their distributors, the “one-stops.” Moving from 78s to smaller discs appealed to the machine operators. Thirty-three inchers, with many selections per side, were unacceptable to the hit-oriented merchandisers. One stops—independent distributors—sided with their best customers, the operators. The short-playing record became the modality for the youth music market. Unit numbers made the popular-music window the most profitable. LPs netted more per unit than their smaller counterparts; nonetheless, the volume was absent. Adults are low or moderate record buyers, regardless of price. Adolescents became a prime industry target.

A & R executives, when not shepherding a record or artist, were known to spend time with the latest issue of Photoplay in order to “psyche out the kids.” Hagiographic stories about Marlon Brando (The Wild One) alerted the bizzers. Sam Phillips of Sun Records would utter the immortal phrase. “If I could find a white boy who could sing like a nigger, I could make a million dollars.” Other executives politely kept the thought to themselves. In 1954, however, the record industry lacked a Brandoesque personality. Perry Como, Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, and even Eddie Fisher were voices out of the past.

The film industry, in dire straits, would probably have welcomed an “insignificant” quarrel over delivery equipment. Instead, film company lawyers were battling anti-trust suits that put the very substructure of the studios in jeopardy. Reeling from the U.S. vs. Paramount et al. decision to divest chain-theater operations, and the unspeakable little glowing boxes placed prominently in the nation’s living rooms, the film community was in a struggle for its very survival. Resorting to “big picture” spectaculars and enhanced technology proved uncertain, garnering diminishing returns. Million-dollar film budgets barely returned enough to keep the major studios afloat.

In simple statistical terms, television devastated filmdom. In 1949 there were one million television receivers. In a five-year span the number rose to thirty-two million. By the end of the Fifties, 90 percent of the American households owned at least one television set and 5,000 movie theaters had closed. The combined profits of the ten major movie studios plummeted from $121 million to $32 million despite a ticket price increase. A more telling comparison is that ninety million tickets were sold per week in 1949 but only forty-five million moved in 1956. The decline occurred although the U.S. population grew by nearly thirty million people during the 1950s. Employment in the film community was nearly halved, going from 24,000 in 1946 to 13,000 ten years later.

Like RCA Victor, the film industry adopted an ostrichlike posture, refusing to deal with the new medium. Television, desperate for film products, was denied the rental of studio vault material. Tied to the concept of “family entertainment,” studios invested in mammoth super-screen technology. Cinerama and Twentieth Century Fox’s Cinemas-cope were unveiled to lure young and old into the sparsely populated movie houses. Bankable names were signed to star in the wide-screen extravaganzas. Sound enhancement and abortive 3-D experiments were other ploys for increasing attendance at indoor showings. These innovations failed to aid most besieged exhibitors. A Sindlinger study found that during television’s prime growth period, 1946 to 1953, 5,038 theaters folded. All but 334 drive-ins were “four-wallers.” Business Week pointed to drive-ins, unaffected by Hollywood’s new technology, as the “one shining exception” to the ravaged movie theaters.

Another study, vintage 1953, painted an even bleaker picture. The researchers found that 41 percent of indoor theaters were supported by their concession income, as opposed to 24 percent of drive-ins.3 Hollywood’s scarce resources, it appears, were going to the wrong exhibitors. Outdoor theaters were attracting entire families piled into the proverbial station wagons. John Durant noted, “It doesn’t seem to make much of a difference what kind of pictures are shown, because drive-in fans are far less choosy.”4 The “junk” fare, in the words of a California outdoor exhibitor, would eventually drive Mom and Dad back to their glowing hearth while the drive-ins “gave way to teenage exploitation films.”5 As Jarvie nicely summarized the audience trends of the period, “The hard core is mainly the young and the unmarried who want to escape home and television.”6 The same description applied perfectly to “heavy” record buyers.

The time was not yet at hand for the studio community to realize the value of demographic analysis; instead the “great man” theory continued as film companies pursued a nebulous mass audience. The search for “hot” properties, producers, and personalities went on as usual. The expense of blockbusters soared. My Fair Lady (1952) cost $5.5 million, The Robe (1953) was made for $5 million, and another Biblical epic by C.B. DeMille, The Ten Commendments (1956), was delivered at $13.5 million. As the expenses mounted, the number of players inversely decreased. Financial backers demanded ironclad scripts and stars.

“With higher admission prices, the favored movies turned bigger profits,” said Sklar. “The gold was there to be mined, only fewer people could share in it.7 A back-to-basics approach...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Rock Around the Clock: The Changing of Popular Music

- 2 It's Only Make Believe (1958-1963)

- 3 Help! I Need Somebody

- 4 Shake That Moneymaker

- 5 Post-Fever Blues

- 6 It Was the Year That Wasn't: 1982

- 7 Movie + Soundtrack + Video = $$$!!!

- 8 Synergizing 1984?

- 9 Soundtrack Wars

- 10 Soundtrack Fever II

- 11 Goooood Morning, Vietnam!

- 12 Holy Boxoffice, Batman!

- 13 On the Cutting-Room Floor: Epilogue

- Bibliographical Notes

- Index