eBook - ePub

Progression in Primary Science

A Guide to the Nature and Practice of Science in Key Stages 1 and 2

- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Progression in Primary Science

A Guide to the Nature and Practice of Science in Key Stages 1 and 2

About this book

Using many examples drawn from classroom practice, this guide supports and aims to extend the student teacher's own subject knowledge and understanding of science in the context of the primary classroom. It offers an accessible guide to all the main concepts of Key Stages one and two science teaching. Illustrating the importance of issues such as resourcing and assessing science in the primary classroom, the book offers guidance for practicing teachers who consider themselves "non-specialists" in science.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Scientific Enquiry

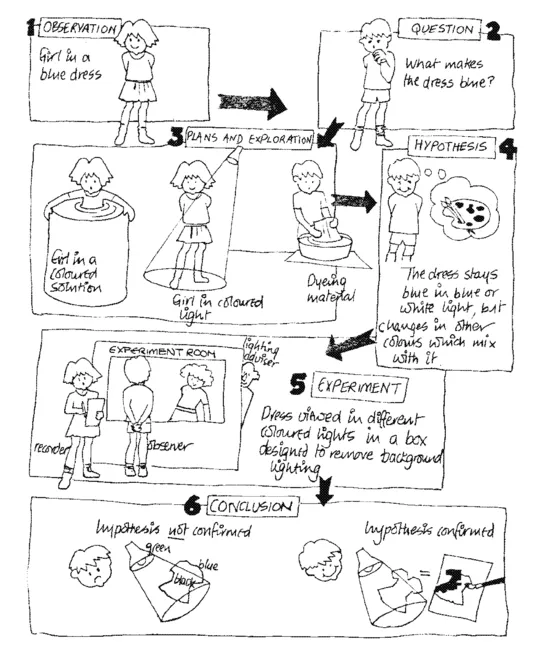

Science is often thought of as certain kinds of information, for example 'How dinosaurs lived, and why they became extinct'. It can equally well be characterised as a process of enquiry — how we find out about dinosaurs rather than what we know about them. In this chapter we will explore this process, usually called 'investigating', as it is practised by children and by scientists, and how it is to be implemented in schools to meet the requirements of the curriculum. Firstly, let us analyse an enquiry by a child (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The process of science investigation

The process skills of science

John asked the question: 'Why is Lisa's dress blue?' This is prompted by an observation that it is blue, and more importantly, that it is a matter of interest. What kind of answer is expected to this question? 'Because Lisa is wearing the school uniform' will not result in any further enquiiy, so we need to elicit from John why he finds this question interesting. It may be that he has clone some work on mixing paints to make different colours and wonders if the same thing happens with cloth. He may have noticed that clothing seems to change colour under disco lighting. After exploratory activity and discussion, John decided to focus on the question of coloured light falling on coloured cloth. He was able to formulate a prediction: 'I think that when I shine green light on the blue cloth it will look greeny-blue'. This is related to a more general hypothesis: 'Coloured lights have the same effect as coloured paints'.

This can now be tested, but he needs to plan how the test can be made fair. Does he really need Lisa, or only her dress, or would any sample of blue material be suitable? How should he arrange to shine the green light? Does all other light need to be excluded? How bright is the light to be, and what shade of green? All these factors could affect the result. They are variables to be investigated or controlled in the experiment.

The observations or measurements he makes provide the evidence; it is important to record this carefully so that it can be correctly interpreted. For example, it will probably make a difference to his results if the colour of the light is different shades of green and the colour of the fabric is different shades of blue. Unless this is systematically recorded then the wrong interpretation could be made. The final step is to compare the results with the prediction and draw a conclusion. In this case, if the light was pure green and the fabric was pure blue then the fabric's appearance would be black. This would not confirm the hypothesis. If however, as is more likely, neither colour is pure then John would get the result he expected and his hypothesis would be confirmed.

This seems disturbing — how can we accept the possibility of conflicting conclusions from the same investigation? This is the reality of the situation, however, and it points to three conclusions about the nature of the scientific process. The first is that repetition is important. Anyone could confirm John's results with the same lamp and the same fabric. The second is that evaluation and communication must be an essential part. The contributions of several investigators can then be combined to perhaps discover that it is the variations in the shade of the colour that give these apparently conflicting results. Finally, the conclusions of the enquiries should always be considered as provisional knowledge. In this case John's ideas could be replaced by a better hypothesis or theory of colour mixing, as described in Chapter 4 of this book.

This example highlights the important relationship between ideas and evidence, in science. Until John had formulated an idea, he could not gather the evidence to test it. In shaping this idea he used some previous knowledge creatively, in the context of his observation or question.

The processes of linking ideas to evidence are what give science its identity. They are always similar, no matter what the area of enquiry. The processes are described by 'doing words' given below in bold. They can be grouped into three clusters:

- planning including formulating questions from significant observations, making predictions and hypotheses which can be tested, planning fair tests in which variables are controlled;

- doing including selecting and using equipment, observing and measuring to collect evidence, recording data;

- interpreting including organising and presenting results, concluding with respect to predictions or hypotheses, evaluating experimental work and findings, communicating to others.

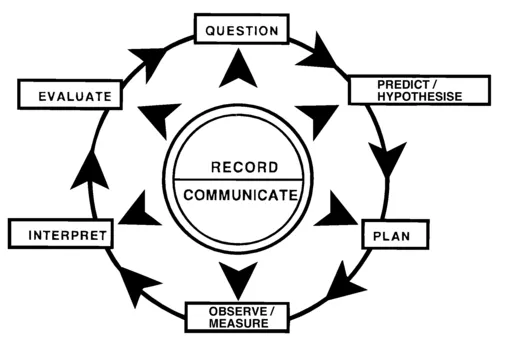

These could be seen as the before, during and after stages of the experiment, but often there are trial and exploratory stages, so the whole enquiry has more of a cyclic nature (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The skills of science investigation

Sex, drugs, disasters and the extinction of dinosaurs

Here is a story from science in which the same processes are operating (Gould 1984).

Dinosaurs, their lifestyles, death, and the possibility of their reincarnation in our own times has fascinated people long before the Jurassic Park movie. Evidence of how they lived comes from fossils, as does the evidence of their mass extinction after 100 million years of global domination. Quite simply, their fossil record read from rock dating stops 65 million years ago, The science begins with this observation, which may also be expressed as a question: What happened 65 million years ago? This might be thought rather hard to answer, but, perhaps surprisingly, several explanations have been offered by scientists in recent decades.

These are the hypotheses:

- sex: there was a global warming at that time; dinosaurs being large were unable to cool their bodies sufficiently, the males' testes got overheated and they became infertile;

- drugs: flowering plants evolved at that time; many of these contain toxic substances to protect themselves from being eaten, dinosaurs didn't recognise this and died of poisoning;

- disasters: there was an impact of a large asteroid at that time; the debris it created blocked the sunlight and cooled the planet so dramatically that many species died of freezing or starvation.

These hypotheses need to be tested; investigations require planning so that evidence can be collected. How is this done? The only source of evidence for events so long ago is found in the rocks and other deposits that were formed at the time. Testes do not fossilise so it is impossible to know whether the sperm were infertile, so the sex hypothesis cannot be tested. For the drags hypothesis, there is fossil evidence that many dinosaur bodies were distorted in death, which could suggest that they died in agony from poisoning. However, there is a simpler interpretation — the distortion was caused by muscle contraction after death, and by movement of the rocks later. Nor can the drugs idea explain why many other species became extinct, or why dinosaur extinction happened tens of millions of years later than the evolution of flowering plants. Evidence for the disaster hypothesis is from deposits of unusual materials at that time, as would be expected from the collision of an asteroid. Other scientists argue that these materials could have come from within the Earth as a result of volcanic activity. Their evaluation of the evidence does not destroy the idea completely; there would still be a dust cloud blocking the Sun, but its source has been modified.

This 'atmospheric disaster' hypothesis is currently the best theory of how the dinosaurs, and many other species, became extinct 65 million years ago, even though there is no general agreement on all the details. The theory evolved by scientists communicating; more significantly, they discovered something entirely new as a result. This is even more important to humans than the extinction of the dinosaurs — the possible extinction of the human species! It was previously thought (by those who can contemplate 'megadeaths') that a nuclear war was winnable. It would take a while for radiation to fall in bombed areas, but then they could be invaded. When this 'atmospheric disaster theory' was applied to nuclear war, it showed that the whole Earth could become uninhabitable because of the debris and smoke from fires blocking the Sun for years. The influence of this theory is believed to have helped end the nuclear arms race between the USA and USSR.

This story makes the case that the process of investigation is more important than the facts it establishes — we still don't know for sure what killed off the dinosaurs, but we may have avoided killing ourselves off.

In the National Curriculum for science in England the first part of the programme of study covers scientific enquiry (often referred to as Sc1). Investigative skills are listed in three stands called 'Planning', 'Obtaining and presenting evidence' and 'Considering evidence and evaluating'. Similar strands feature in the curricula of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. In addition the strand 'Ideas and evidence in science' raises the underlying basis of scientific enquiry — the way in which ideas are generated so that investigations can gather evidence to test and develop them. This can be addressed by children thinking about their own ideas and how they tested them, as in the example of John at the beginning of this chapter. An alternative way is to feature this aspect in examples of the work of scientists, such as this dinosaur example.

Knowledge, understanding and skills in school science

For school science there has been considerable debate over many years about the relative importance of the content of science — facts and theories to be known and understood; and the process of science — skills and procedures to be practised and used. Defining the content can be important because:

- it is impossible to cope with all possible enquiries that children may have, so there needs to be some selection;

- certain knowledge and understanding is particularly fundamental in order to understand the world;

- certain knowledge and understanding is especially useful, and is motivating for children;

- children do not know which knowledge is the most important;

- teachers need help in providing a balanced Content;

- schools need help to cover suitable content at the best time and to prevent omissions and duplications;

- an agreed content results in a more valid assessment of pupils' learning.

The arguments for emphasising processes include:

- what is considered the most important knowledge and understanding will change with time, because that is the nature of science;

- what is useful and motivating to children will depend on the children concerned and will vary;

- specifying the content inhibits the way in which the teaching is organised, e.g. making topic approaches more difficult;

- these skills help children to behave in a scientific way;

- the skills and procedures of investigating can be applied to new content and make it easier to understand;

- a process approach emphasises the need for active engagement by the learner, and this is a more effective way of developing understanding.

The requirements of the curriculum for science in primary schools reflect this debate. Content and process are both specified, and are supposed to be given equal weighting in the planning of activities — and in the assessment of pupils. However, there is also an emphasis on the relationship between content and process: the skills have to be practised and used on some scientific content, and the knowledge and understanding will be gained through the use of a skill. For example, CD—ROMs can be useful stores of scientific knowledge and understanding, but one needs to learn information technology access skills to make use of them. This book represents a body of science content grouped around a major theme in each chapter. The writers assume that the readers will have the study skills to learn some science from this content, but also hope that such learning will be supplemented with activities which develop the reader's scientific skills as well!

How can children develop the skills of science?

It is appropriate to consider children developing these skills rather than learning them, as it can be argued that children have been using them to make sense of their world from a very early age. Research in recent years has produced some remarkable findings, through ingeniously devised experiments, such as mobiles which can be controlled by babies' hands, or lights which respond to their head turning. Babies of only a few months old have been found to explore a world that they conceive to be 'out there' and to be able to affect this world in ways that they choose. Researchers think that this process can have important consequences for their later development (Donaldson 1992).

By the time that children start nursery school they will have had considerable experience of interacting with the world in an investigative way. The role of the teacher, therefore, is that of developing these skills by selecting scientific contexts which draw on children's personal experiences and challenge them to progress further. The statements of curricular requirements chart the directions of that progress.

For example, in the National Curriculum for science in England, five levels of attainment are identified, each representing, in broad terms, a year or two of a child's school career. The way these skills are seen as developing is set out in level descriptions so that teachers can recognise progress and pitch their teaching appropriately. An abbreviated version of these descriptions is shown in Figure 1.3 to emphasise progression across the five levels. Similar descriptions are given in the curricula for Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Figure 1.3 Progression in investigative skills by level (Attainment target Sc 1.2)

Practical, hands-on experience is clearly essential in developing these skills. Indeed 'good' science teaching is often seen as synonymous with practical activity. In reality things are a little more complex. Practical work is not necessarily investigative, and investigating is not always 'hands-on'. A useful analysis of types of practical work was published at the time of the introduction of the National Curriculum. Four distinct purposes were identified:

- development of basic skills — e.g. practice in using a thermometer or microscope;

- 2. illustration of a principle, idea or concept — e.g. that water boils at 100°C, that day and night are caused by the rotation of the Earth;

- 3. observation — the differences between two flowers or two local habitats, the speed of a toy on a ramp;

- 4. investigation — a full enquiry in which the practical work is preceded by questioning, predicting and planning and is followed by interpreting, evaluating and communicating.

Each of these has a valid place in the teaching of science, but only the last one involves all the investigative skills.

It may be noted at this point that there is a common misconception about the word 'experiment'. It is often used in the form 'an experiment to prove that pure water boils at 100°C'. This is an example of point 2; not an experiment but an illustration of a principle — science has defined that pure water boils at this temperature. As part of an investigation into wat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Original Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- Introduction

- 1 Scientific Enquiry

- 2 Life Processes and Living Things

- 3 Materials and their Properties

- 4 Physical Processes

- 5 Planning Primary Science

- 6 Assessing Primary Science

- Appendices

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Progression in Primary Science by Martin Hollins,Maggie Williams,Virginia Whitby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.