![]()

Part I

Etiology of psychopathy

![]()

1

Psychopathy and crime are inextricably linked

Matt DeLisi

Introduction

The human population is marked by extraordinary heterogeneity in terms of behavioral functioning and capacity for norm-violating, antisocial, and violent behavior. Some individuals are exceedingly compliant, self-disciplined, and easy to get along with in terms of their basic nature, characteristics that personality psychologists would recognize as high Conscientiousness and high Agreeableness. These individuals tend to do very well in life and experience success in their family relationships, their school and work careers, and their ability to lead a crime-free life. Most individuals – comprising the bulk of the population – also do fairly well in terms of their ability to get along with others and regulate their conduct. Although they are not as ascetic as the former type of person, they nevertheless are able to regulate their conduct appropriately in most situations and in accordance with societal demands. And a fairly small number of individuals, certainly less than 5 percent of the human population, are generally noncompliant, have difficulty regulating their conduct, and face many hardships due to their unwillingness and incapacity to get along with others (DeLisi, 2005; Vaughn et al., 2011; Vaughn, Salas-Wright, DeLisi, & Maynard, 2014). Indeed, empirical assessment of the most serious, chronic, and violent offending pathways inevitably comports with persons that are also the most psychopathic (Baskin-Sommers & Baskin, 2016; Colins & Vermeiren, 2013; McCuish, Corrado, Hart, & DeLisi, 2015; McCuish, Corrado, Lussier, & Hart, 2014; Vaughn, Howard, & DeLisi, 2008).

When considering the three types of people that were just described, the highly compliant and highly self-regulated, the moderately compliant and generally well-regulated, and the chronically noncompliant and difficult, distinct and significant differences can be observed in terms of their behavioral functioning and in the diverse ways that one’s sense of self relates to other people. The highly compliant individual is almost selfless in the way that he or she modulates and controls his or her thoughts, impulses, emotions, and behaviors. Such a person is able to inhibit conduct even in challenging contexts in favor of the greater good. The moderately compliant individual occasionally prioritizes themselves over the greater good. In this way, he or she periodically engages in selfish, self-centered, or narcissistic acts where the benefits of an immediate behavioral choice are selected in favor of a different behavioral choice. Many crimes can be understood from this basic calculation of self-regulation and the self. For instance, drunk driving is an immediate attempt to provide some benefit (e.g., driving home in the comfort of one’s own vehicle) as opposed to a costlier alterative (e.g., paying for a taxicab, taking the bus, and thus having to pick up one’s vehicle the next day because of one’s current intoxicated state). Theft can provide something of value now as opposed to engaging in some delayed (e.g., waiting in line to purchase the item) activity. In both of these examples, drunk driving and theft, consideration is also not given to how the behavior negatively affects other people, whether other motorists that could be placed in danger by the individual’s intoxicated driving or the shopkeeper whose livelihood suffers from the lost sale.

In the extreme case, for instance an individual whose entire behavioral repertoire is motivated by impulsive self-interest and virtually absent self-regulation, very serious crimes can occur. Sexual homicide is an example. Here, an offender procures a suitable victim, usually by force, and then sexually abuses and kills the victim. The reasoning or motivation is simple: the person wanted to engage in these behaviors and does not consider the effects on the victim or the victim’s surviving family. Certainly more extreme than theft or drunk driving, the focus on the self and one’s selfish desires is the driver of the conduct and is nevertheless the same as the mundane criminal acts.

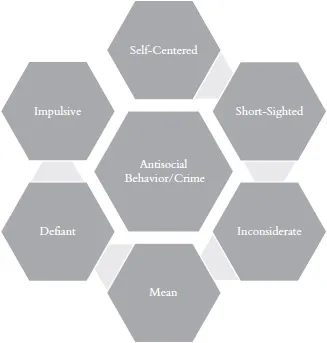

In previous works (DeLisi, 2009, 2016), the current author has suggested that psychopathy is the unified theory of crime because the basic characteristics that comprise the disorder effectively map onto the basic characteristics of antisocial and criminal behavior. To use the aforementioned examples of crime, and as shown in Figure 1.1, antisocial behavior or crime can be understood as a behavioral action that is self-centered, short-sighted, inconsiderate, impulsive, defiant, and mean. Not all of these characteristics must be present to coincide with every criminal act, but these elemental characteristics are at the heart of antisocial conduct, particularly when a multiplicity of these characteristics is present. To illustrate: in isolation, these characteristics can produce negative situations relating to impulsivity (e.g., buying clothing on impulse when one cannot afford it), self-centeredness (e.g., looking out for oneself at the expense of one’s friends or family), short-sightedness (e.g., refusing to study for tomorrow’s exam because one is tired now), meanness and inconsideration (e.g., making fun of a colleague without thinking of how the teasing negatively affects the target), or defiance (e.g., refusing to follow procedures at work). However, these isolated manifestations of crime characteristics do not necessarily mean that one will commit crime.

Figure 1.1 Elemental characteristics of antisocial behavior/crime

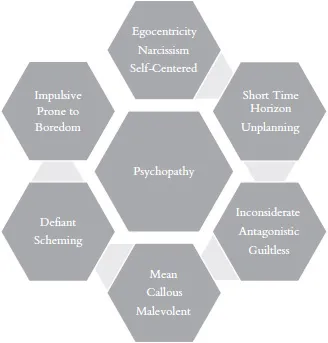

But what about when the assorted characteristics of crime are repeatedly apparent in the disposition and behavioral actions of an individual? As shown in Figure 1.2, if one extrapolates the elemental characteristics of crime, the result is effectively a listing of psychopathic traits. The self-centeredness of committing an antisocial act is congruent with the egocentricity, self-centeredness, and pathological narcissism of the psychopath. The short-sightedness of an antisocial act is consistent with the short time horizon, unplanning, and low wherewithal of the psychopath. Inconsideration involved in antisocial conduct is conceptually similar to the antagonistic, inconsiderate, blaming, guiltless, remorseless features of the psychopath. The meanness inherent in victimizing a person or property dovetails with the psychopath’s mean, callous, indifferent, and malevolent disposition. Defiant action is matched by the defiance, scheming, and manipulative nature of the psychopath. And impulsivity of crime matches the impulsivity, proneness to boredom, and sensation seeking of the psychopath. Perhaps rivaled by no criminological theory but self-control theory (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990), the theory of psychopathy provides the instantiation of the antisocial person.

Psychopathy also maps well onto the most troubling typologies of offenders, such as those that evince chronic, serious, and violent offending trajectories. For example, using the Comprehensive Assessment of Psychopathic Personality (CAPP) framework, Corrado, DeLisi, Hart, and McCuish (2015) suggested that the behavioral and cognitive domains of psychopathy are particularly facilitative of chronic offending, including the traits of impulsivity, disruptiveness, aggressiveness, unreliability, restlessness, and the lack of perseverance. Chronic offenders are also theorized to be cognitively intolerant and suspicious of others, unfocused, and lacking plans for the future. They are aimless, disorganized, and prone to a transient lifestyle that also sustains frequent criminal activity and criminal justice system involvement. Serious offenders are theorized to draw most of their negative personality features from the dominance and self domains the CAPP model. For instance, serious offenders are characterized as self-centered, self-entitled, self-aggrandizing, self-justifying, and tend to view themselves as invulnerable and risk-taking. In terms of dominance features, serious offenders are portrayed as domineering, manipulative, antagonistic, insincere, and deceitful. Violent offenders are theorized to derive their traits primarily from the attachment and emotional domains of the CAPP model. Violent offenders are theorized to be remote, cold, cruel, callous, and thoroughly inconsiderate of others and, in terms of their emotional life, are fearless, unconcerned, dark, indifferent, irritable, and unrepentant. These traits allow them to inflict violence on victims without feeling any of the self-sanctioning emotions that inhibit such conduct among non-psychopathic persons.

Figure 1.2 Elemental characteristics of psychopathy

Psychopathy can be understood as an organizing construct for other foundational correlates of crime. For instance, sex is the most powerful demographic correlate of crime and far exceeds the effects of other important factors, such as age, race, ethnicity, and social class. In a recent study, Gray and Snowden (2016) examined the inter-relationships between sex, psychopathy, and various forms of crime and criminal justice system noncompliance using data from the Partnerships in Care and the MacArthur Risk Assessment Study. Among data from the Partnerships in Care study, males were significantly more superficial, grandiose, remorseless, irresponsible, and antisocial during both adolescence and adulthood. In the MacArthur study, males were significantly more superficial, grandiose, remorseless, unempathic, irresponsible, impulsive, and antisocial during both adolescence and adulthood. On no feature of psychopathy were females more severe than males, suggesting that a simple indexing of psychopathic features is another way to index sex differences in criminal conduct. Irrespective of sex, psychopathy was significantly correlated with reconviction at two time-points and aggression and violence at two time-points.

The current chapter reviews recent criminological research that has focused on the associations between psychopathy and diverse forms of antisocial conduct, crime, and violence. It is noteworthy that no study exists, to my knowledge, that has found that psychopathy was unrelated to crime and various aberrant conduct. When considering the diversity of research findings and the diverse forms of antisociality therein, the intimate connection between psychopathy and crime becomes even more clear.

The psychopathy and crime mutuality

Many colorful passages have been published to demonstrate the powerful linkage between psychopathy and crime. The following by Arboleda-Flórez (2007:375) is among my favorites:

Psychopathic tendencies are noticeable even in young children who later become known for their continuous lawbreaking and inability to live within the rules of society. Psychopaths carry a historical load of reported difficulties at school, in the military and at work, besides police reports and court dockets. Like a hurricane, psychopaths leave a path of broken promises, damage to property, physical or sexual abuse, rape, mayhem, murder and destruction of the dreams of others.

Psychopathy rears its ugly head almost irrespective of context, even when considering mundane behaviors in the workplace such as using a computer. For instance, there is evidence that persons with more psychopathic personality traits are more likely to engage in counterproductive work behaviors that are damaging to their employer (Blickle & Schütte, 2017). Similarly, using an online sample of participants recruited from MTurk, Siegfried-Spellar, Villacís-Vukadinović, and Lynam (2017) examined associations between psychopathy and diverse forms of deviant computer behaviors, including gaining unauthorized access to a network, writing/creating computer viruses, engaging in identity theft or fraud, monitoring network traffic, and website defacement. Using the Elemental Psychopathy Assessment Short Form (EPA–SF), they found significant correlations between total psychopathy scores and all forms of computer crime. The correlation was strongest for total computer crime. In addition, psychopathy had significant inverse correlations with Agreeableness and Conscientiousness and significant positive correlations with total antisocial behavior, violent crime, nonviolent crime, alcohol use, and DUI. In other words, although their focus was on the association between psychopathy and computer crime, it quickly became clear that the construct unfolds to affect generalized involvement in an array of offenses.

There is ample evidence for the psychopathy-generalized offending link. Using data from 103 females selected from forensic settings and 274 females selected from school settings in Portugal, Pechorro, Gonçalves, Andershed, and DeLisi (2017) found that psychopathy was significantly correlated with a broad range of outcomes, including proactive aggression, reactive aggression, violence, alcohol use, drug use, and having an earlier starting delinquent career. More psychopathic juvenile offenders also have an earlier age of onset of antisocial conduct, an earlier age of onset of police contact, and an earlier age of incarceration, in addition to more self-reported delinquency and more severe/serious delinquency (Pechorro, Maroco, Gonçalves, Nunes, & Jesus, 2014). Put another way, the most psychopathic youth will be those that are the most precocious offenders and those whose delinquent activity most quickly activates the discretion of law enforcement and the juvenile court.

Offenders with more extensive psychopathic features have also been shown to recidivate at higher levels, recidivate faster after release from custody, and recidivate with more dangerous crimes than their non-psychopathic peers (Shepherd, Campbell, & Ogloff, 2018; Thomson, Tiihonen, Miettunen, Virkkunen, & Lindberg, 2018), and these relationships have been shown using data from multiple nations. For example, Gretton, Hare, and Catchpole (2004) analyzed data from boys that had been referred to Youth Forensic Psychiatric Services in Canada and followed over a ten-year period. The investigators divided the youth into low, medium, and high grouping based on their scores on the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL: YV). The most psychopathic youth were worse in history of abuse, including physical, sexual, and emotional victimization, prevalence of substance abuse, and Conduct Disorder symptoms. They also had the most collective involvement in violent, nonviolent, and sexual offending. The follow-up results were eye-opening. A gradient was seen in terms of prevalence of recidivism and the adolescent psychopathy profile. ...