- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Political and Military Sociology continues a mission of publishing cutting-edge research on some of the most important issues in civil-military relations. In this inaugural volume of the new annual publication, Won-Taek Kang tackles the issue of nostalgia for Park Chung Hee in South Korea, and analyzes why many South Koreans today appear to miss the deceased dictator. Ryan Kelty, Todd Woodruff, and David R. Segal focus on the role identity of U.S. combat soldiers as they balance competing demands made by the military profession, on the one hand, and solders' family and personal relations, on the other.D. Michael Lindsay considers the impact that social contact has on military and civilian participants in the elite White House Fellowship program, and analyzes how social contact affects the confidence in the U.S. military that civilian fellows later show. Analyzing letters to the editor of a local newspaper, Chris M. Messer and Thomas E. Shriver consider how community activists attempt to frame the issue of environmental degradation in the context of a local dispute over the storage of radioactive waste. David Pion-Berlin, Antonio Uges, Jr., and Diego Esparza analyze the recent emergence of websites run by Latin American militaries, and consider why these militaries choose to advertise their activities on the Internet.Political and Military Sociology also includes reviews of important new books in civil-military relations, political science, and military sociology. Included here are discussions of books about U.S. war crimes in Vietnam, civil-military relations in contemporary China, the structural transformation of the U.S. Army, Japanese security policy, American treatment of POWs, the Bonus March, and the GI Bill.The series will be of broad interest to scholars of civil-military relations, political science, and political sociology. It will continue the tradition of peer review that has guaranteed it a place of importance among research publications in this area.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Political and Military Sociology by Jonathan Swarts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

U.S. Military and the White House Fellowship: Contact in Shaping Elite Attitudes

D. Michael Lindsay

Gordon College

Gordon College

Political and Military Sociology: An Annual Review, 2010, Vol. 38: 53–76.

By examining the role of one of the nation’s most elite networks, the White House Fellowship, I test the effect of social contact on elite attitudes toward the U.S. military, an institution that has long been powerful but has been increasingly excluded from the rarefied world of social, cultural, and intellectual elites. Using qualitative and quantitative data from the first study conducted with White House Fellows in the program’s forty-five-year history, I show how peer contact within classes of Fellows between military and civilian participants significantly increases the odds of having a great deal of confidence in the U.S. military.

In the aftermath of World War II, a number of social observers expressed concern about the ongoing influence of the U.S. military even in peacetime. In the 1940s, the U.S. military had expanded in unprecedented manner as America supported and then joined the Allied Forces, but there was no corresponding reduction in the ten years following their victory. In this context, C. Wright Mills (1956) emerged as one of the most vocal opponents of America’s military-industrial complex, which, he argued, had become the power elite’s source of structural cohesion. In essence, he claimed it was a tripartite arrangement that kept in power a select group of senior political figures, the military’s top brass, and executives at those companies that served the Pentagon’s insatiable appetite for weaponry. In turn, this power structure stripped the American people of the influencethey ought to exercise in a democratic society. He wrote, “Mass society is the obverse of the power elite; as power has been concentrated at the top, the mass has been denuded of it” (Mills 1956:19).

In the decades since Mills wrote The Power Elite, the Pentagon has continued to exercise enormous influence in U.S. policy-making. Although Dwight D. Eisenhower was the last U.S. general to be elected to the nation’s highest office, many senior military officers have occupied powerful positions (such as former Secretary of State Colin Powell) or run for president (such as General Wesley Clark). At the same time, however, power and influence are not synonymous with status or prestige. Despite the military’s prominence in policy-making and the significant funding it receives in the federal budget, the U.S. military does not enjoy the same esteem—especially in elite quarters—that it once did. Look no further than the response of America’s most selective universities toward military recruitment on campus. In 1969, the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps was asked to leave the Harvard campus in a symbolic move that underscored the university’s opposition to the Vietnam War. Another move occurred in 1990, when the Association of American Law Schools added sexual orientation to its nondiscrimina-tion policy. At that time, Harvard Law School (along with other member schools) banned any company that could not certify its compliance with nondiscrimination toward homosexuals from recruiting students on campus, including the U.S. military.1 Although there have been ongoing battles between the university and members of the U.S. Congress on this subject—members of Congress have sought to withhold federal research funds from Harvard until the institution welcomes military recruiters—those efforts have been largely unsuccessful. As recently as the spring of 2009, Harvard Divinity School hosted a gathering (co-sponsored by Harvard Law School and the Dean’s Office) entitled “Ivies and the Military: Toward Reconciliation,” which sought to facilitate a rapprochement between the two groups.

There is, however, one mechanism that has bridged the divide between military and civilian segments of the nation’s elite in recent decades. Drawing on Allport’s (1954) original theory of social contact, I show how contact among career military elites of equal status with civilian elites can significantly enhance the odds of civilians holding a positive view of the U.S. military. By “elites” I mean those people who hold positions of authority within major social institutions, a definition that is in line with many previous works (Mills 1956; Giddens 1973; Putnam 1976; Moore 1979; Marger 1981; Dye 2002). Of course, scholarly definitionsof the term vary, a fact that complicates comparative studies (Kerbo and Della Fave 1979; Burton and Higley 1987). Some define it through social class or membership in selective clubs (Baltzell 1953; Marcus and Hall 1992; Broad 1996), and I recognize the potential overlap between these class-based and positional definitions. A few dilute the term by including professional managers (Ghiloni 1987; Lerner et al. 1996), but I prefer to keep the definition more selective, focusing on those at the very top of organizational life.

To test this theory, I analyzed survey and interview responses from the 1965–2008 classes of the White House Fellowship (WHF) program, the nation’s most selective fellowship that includes regular interaction between military and civilian leaders (most of whom are in their thirties). Distinguished alumni of the program include General Wesley Clark, former Cabinet Secretaries Henry Cisneros and Elaine Chao, and CNN medical editor, Sanjay Gupta. Former Secretary of State Colin Powell has commented about his fellowship experience:

The aim of the program was to let us inside the engine room to see the cogs and gears of government grinding away and also to take us up high for the panoramic view. In all the schools of political science, in all the courses in public administration throughout the country, there could be nothing comparable to this education. (Powell 1995:176)

The WHF thus represents an ideal case study for analyzing civilian-military interaction and its effect among American elites, because the program’s alumni occupy senior leadership positions in nearly every sector of society, including business, academia, government, nonprofit life, and the military. In this article, I examine the extent to which White House Fellows’ interaction with the military during their fellowship year predicts levels of confidence in the U.S. military, net of other factors. I supplement this with interview data and show how identity-shaping mechanisms such as yearlong fellowships can trump other sources of identity and then conclude by suggesting how this might realign our understanding of how elite attitudes are formed.

Status, Power, and the U.S. Military

Elites wield power that is disproportionate to their number in society overall, but research suggests that a similar stratifying trend exists even within the higher circles. In other words, status hierarchies persist within the rarefied world of elite influence. Wealthier elites or those who went to certain schools wield greater power than do others within the samesocial network, even if all members are presumed to be peers (Zald 1969; Granfield and Koenig 1992). In Domhoff’s (1974) description of the Bohemian Grove, one sees how status and power differentials operate even within a very elite group. This, in turn, can draw certain individuals to the center of that power and leave others, to borrow Moore’s (1988) pithy phrase, as “outsiders on the inside.” One important currency of elite influence is prestige. The quest for prestige in the eyes of elite peers (and their families) has been shown to be a catalyst for educational, social, and occupational credentials—which are then used for acquiring greater power (Collins 1979). Prestige and status also push individuals to conform (Tumin 1953; Bourdieu 1984). Hope (1982) distinguished between the objective rewards and the subjective approvals associated with prestige. But perhaps most intriguing, he argued that prestige changes with social context. What is considered prestigious in one society is not necessarily so in another.

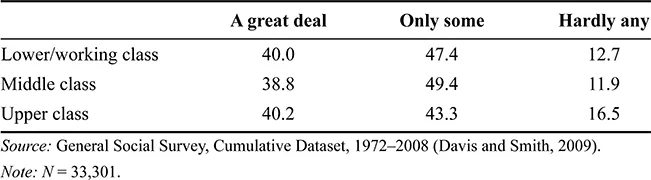

That raises a question about elite attitudes regarding certain institutions such as the arts, the scientific community, or the Pentagon. I am particularly interested in elite attitudes toward the U.S. military, for it occupies a liminal space—in some ways at home within the nation’s upper reaches and in other ways distant from the enclaves of elite society. National survey data demonstrate ongoing distance from the military within elite circles. As Table 1 shows, members of the upper class are significantly more likely to express “hardly any” confidence in the U.S. military, compared to members of the lower/working or middle classes (Rao-Scott adjustment to the chi-square statistic = 9.82; p = .00). Of course, upper-class attitudes cannot be directly mapped onto those who hold positions of authority within major institutions, which is how I define “elite” in this article, but these data do indicate statistically significant differences of opinion among various strata of society. As will be shown, however, even these attitudinal differences can be moderated or changed by several important factors.

Given the number of studies that have shown that a person’s contact with a member of a certain group can reduce the person’s bias against that group—if certain conditions are met (Pettigrew 1998)—it stands to reason that if more elites had contact with career military officers, their level of confidence in the institution would likely rise.

Indeed, as Allport (1954) originally argued, contact among people of equal statuses but different backgrounds can lessen conflict and prejudice as those individuals engage one another. For example, in situations whereblacks and whites interact under optimal conditions—meaning that the people are basically of equal social status, have common goals with no competition, and the contact is allowed by authority figures—there is a significant lessening of racial prejudice. Since its original formulation, social contact theory has been tested in hundreds of empirical analyses and has been helpfully applied to numerous social interactions, including public school desegregation (Stephan and Rosenfield 1978), mainstreaming disabled children (Harper, Wacker and Cobb 1986), and resolving ethnic tensions (McLaren 2003). What we do not know, however, is how social contact within certain networks of people—especially at the elite level—might affect attitudes toward institutions such as the U.S. military.2

Table 1 Percentage of confidence levels in the U.S. military

Further, we know that networks not only serve as conduits of meaning and information; they also play large roles in constituting and constructing meaning for individuals and their identity (Fiske and Taylor 1984; Swidler 2001). As Stromberg (1993) argues, the retelling of stories and the sharing of individual perspectives that takes place as one talks to another person or a group constitutes a way in which he or she reconstructs the meaning all over again. Moreover, examining these acts of meaning-making are important because they can coordinate action over time and facilitate elite power. Relational ties and how individuals talk about them indicate not only attitudes but also the perceptions of those attitudes that empower elite action (or inaction). Research has shown that strong network ties build cohesion among elites (Useem, 1979, 1984), but weak ties are useful for things like gathering information and closing business deals (Granovetter 1974; Mizruchi and Stearns 2001). How do these different kinds of network ties and the information that they generate and transmit affect elite attitudes within the WHF? We turn now to examine this particular case of an elite network and evaluate how ties within it affect attitudes toward the military.

Data and Methods: The White House Fellowship

President Lyndon Johnson established the WHF as a leadership development program for promising young people early in their careers. In the midst of the tumult of the 1960s, the president wanted to bring together emerging leaders in various fields—commerce, science, law, higher education, the arts, the military, and others—while providing them a first-rate education on the process of governing at the highest of levels. Thousands applied to be part of the inaugural class, but when the program began in the fall of 1965, only fifteen young men had been selected.3 Fellows were assigned as special assistants to major Cabinet secretaries and senior administration officials, and President Johnson personally interacted with the Fellows a half a dozen times during the yearlong fellowship. A presidential commission selected this elite cadre of young people for the fellowship. As John Gardner, the driving force behind the program’s start, subsequently stated, “We hoped the program would strengthen the Fellows’ abilities and desires to contribute to their communities, their professions, and the country” (O’Toole 1995:v). Although Fellows were strongly encouraged to return to their chosen professions after completing their fellowship year, the program’s architects also hoped that it might eventually create a “reservoir of able men and women” who would be especially qualified and interested in assuming senior government posts in the future.

Today, the WHF boasts nearly 650 alumni, many of whom have gone on to occupy very senior positions in society, including college presidents, corporate CEOs, U.S. Senators and Representatives, nonprofit executives, senior military officers, and top government officials. Since the WHF’s inception, however, there has not been a systematic analysis of this unique program. In order to begin such an analysis, in the fall of 2008, I directed a seventy-two-question survey of White House Fellows that exp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- From the Editors

- Missing the Dictator in a New Democracy: Analyzing the “Park Chung Hee Syndrome” in South Korea

- Relative Salience of Family versus Soldier Role-Identity among Combat Soldiers

- U.S. Military and the White House Fellowship: Contact in Shaping Elite Attitudes

- Resident Framing and the Public Sphere: Community Conflict over Radioactive Waste

- Self-Advertised Military Missions in Latin America: What is Disclosed and Why?

- Book Reviews

- In This Issue