In the process of formulating any kind of strategy, especially a strategy aimed at addressing a security threat such as terrorism, it is imperative that the threat be precisely defined and delineated. Therefore this volume, which deals with decision making pertaining to counter-terrorism, begins with the issue of defining the threat of terrorism and its unique aspects in contrast with other phenomena, especially those that are similar or parallel to terrorism, such as guerrilla warfare, political protest, criminal activity, and struggles for national liberation.

The Need for a Definition

Issues of definition and illustration are, usually, purely theoretical and intended to allow the researcher to establish a defined, fixed, and accepted basis for the research he is about to conduct. However, when discussing the phenomenon of terrorism, the matter of its definition is a fundamental and essential element for coping with terrorism, an element upon which we must establish a cooperative, international campaign against terrorism.

Modern terrorism relies more and more upon the support of nations. In certain cases terrorist organizations employ means to realize the interests of states sponsoring terrorism, and in other cases their activities are contingent upon the various forms of economic, military, and operational aid they receive from these nations. Certain organizations rely upon state support so heavily that they become the “puppets” of these nations—in accordance with their decisions and under their direction.1 At the present time, it is obvious that terrorism cannot be addressed effectively if the close ties between terrorist organizations and the countries that support them are not severed. But it is impossible to sever those relationships without reaching a broad-based, international consensus regarding the definition of terrorism, and from this, a definition of states sponsoring terrorism and the steps that must be taken against them. It is impossible to reach a broad understanding of the nature of different terrorist organizations, outlawing them and effectively preventing their fundraising and international money laundering without defining the term “terrorism.” The worldwide awakening against terrorism, which is reflected through international conferences, regional discussions by nations, and the like, cannot yield any genuine results so long as the nations participating in these forums cannot agree to a definition of terrorism. As long as there is no agreement as to “what is terrorism?” it is impossible to assign responsibility to nations that support terrorism, to formulate steps to cope on an international level with terrorism, and to fight effectively the terrorists, terror organizations and their allies. Without a definition of terrorism it is impossible to establish international treaties against terrorism, and if international treaties indirectly relating to terrorism are, in any case, written and signed, attempts to implement or enforce them will be unworkable.

An obvious example of this is the issue of extradition. Many countries throughout the world have signed bilateral and multilateral treaties with respect to various crimes. These treaties do not usually relate to terrorist activity specifically, rather they list ordinary crimes for which the perpetrator must be extradited. A significant number of them state explicitly that when the background of the crime is political, the country is under no obligation to extradite anyone—and the background underlying terrorism is always political. This loophole has allowed many countries to evade their obligation to extradite terrorists even though they have signed treaties that would seem to require them to do so. In the United States, for example, in June 1988, a Brooklyn judge rejected a request by the federal prosecutor to order the extradition to Israel of Abd al Atta (an American citizen suspected of participating in a terrorist attack in the West Bank in April 1986 in which four people were killed). The judge stated that a terrorist attack was a political act that promoted the achievement of political aims and that the action had been carried out as part of the uprising in the West Bank to help realize the PLO’s political objectives. According to the judge, this was a political charge that was outside the category of crimes that obligate deportation under the extradition agreement between Israel and the United States.2

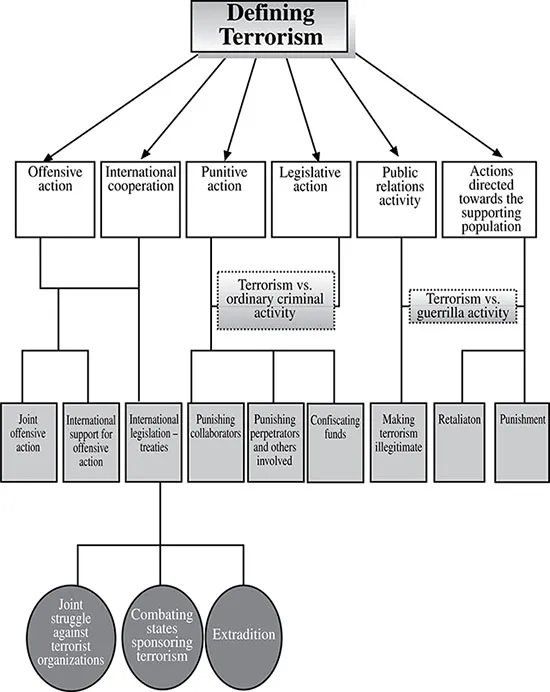

In fact, the need to define terrorism is reflected at almost all levels of our attempts to contend with terrorism (see Figure 1.1), such as:

Legislative action—The laws and regulations enacted to give security forces the tools with which to combat terrorism. The need to define terrorism in this sphere derives from the desire for legislation specifically related to terrorism, for example, laws that prohibit terrorist activity and aid terrorism, as well as laws that establish minimum sentences for terrorists.

Punitive action—As with legislative action, a definition of terrorism is needed for punishing terrorists if we are interested in imposing specific penalties for involvement in terrorist activity (such as sentences for perpetrators and their assistants, confiscation of finances and equipment, etc.).

Regarding legislative and punitive action, we must define terrorism in order to distinguish between this type of activity and ordinary criminal activity even though in both cases— terrorism and crime—the act itself may be completely identical. The need for legislation and punishment that distinguishes terrorism from criminal activity stems from the grave danger terrorism poses to society, its values, the government, and the public order (which far exceeds the risk from criminal activity), due to the political nature of such activity.

International cooperation—In order to strengthen cooperative relationships between nations of the world, and to ensure the effectiveness of such relationships, we must reach an international definition of terrorism that will be as widely accepted as possible. This need is reflected, primarily, in the formulation and ratification of international counter-terrorism treaties that prohibit perpetrating terrorist acts, aiding and abetting terrorist activity, transferring funds to terrorist organizations, state support for terrorist organizations, commercial ties with states sponsoring terrorism and, as stated—treaties that stipulate the extradition of terrorists.

Offensive action—The nation struggling against terrorism must be allowed to take the initiative. At the same time, we must ensure that the terrorist organization’s operative capacity is as limited as possible. Achieving these objectives requires an ongoing and continuous offensive against terrorist organizations. Naturally, countries trying to defend themselves against terrorism win the support of the international community, but countries that launch offensive counter-terrorism attacks are usually vilified and strongly criticized. In order to ensure international support for countries combating terrorism, and perhaps to promote joint offensive action, we must reach an accepted international definition regarding the concept of terrorism.

Actions directed towards terrorism-supporting populations— Often, terrorist organizations need and rely on the assistance of a sympathetic and supportive civilian population. One of the more effective tools for reducing terrorist activity is to eliminate the organization’s ability to receive support, aid, and backing from this population. An accepted international definition of terrorism is likely to fulfill this task. When terrorist activity is differentiated from other types of violence, and when it is agreed that terrorism is not legitimate under any circumstances, then it will be possible to insist that these civilian populations withdraw their support of terrorists, and to couple such demands with appropriate punitive and retaliatory measures.

Defining terror will enable us to define new rules for the domestic and international arena. An organization interested in fighting a state in order to achieve rights or other objectives will have to consider whether to achieve those objectives through terror, or to choose other forms of activity that are not considered illegitimate even if these, too, may very well be violent.

Public relations activity—If terrorism is defined in a way that distinguishes it from other violent actions, it will be possible to initiate an international publicity campaign designed to delegitimize terrorist organizations, cut off their support, and forge a united, international front against them. In order to undermine the legitimacy that terrorist activity enjoys (usually stemming from the world’s tendency to identify with some of the political goals of terrorist organizations), we must differentiate between terrorist activity and guerrilla activity, and view them as two distinct forms of violent struggle that reflect varying levels of illegitimacy.

Thus, defining terrorism is aimed at helping the war on terrorism on many different levels. An accepted definition that can serve as a basis for counter-terrorism activity may also motivate a terrorist organization to reconsider its actions and examine whether it truly wants to continue perpetrating terrorist attacks and risk the loss of its legitimacy, the imposition of severe and specific punishment, collaborative international efforts against it (including offensive action), and the loss of its sources of loyalty, support, and aid; or whether it would be advisable for the organization to choose an alternative type of action (guerrilla warfare, for example), for which they would not have to pay such a heavy price.

The need to define terrorism is particularly obvious in light of the deliberate way in which certain bodies (terrorist organizations, states sponsoring terrorism, politicians, journalists, and others) use many different terms to describe, portray, and analyze terrorism. The perpetrators of a particular attack are liable to be referred to simultaneously by different bodies as “terrorists,” “guerrillas,” “freedom fighters,” “revolutionaries,” and others—all depending on the perspective of the agency and its interests. For example, when the London Financial Times reported on the murderous terrorist attack by Abu-Nidal’s group at the airports in Rome and Vienna in December 1985, it used the terms “terrorists” and “gunmen” on the first page of the paper, but on the second page, the term “guerrillas” was used to describe the same incident. This was true for other newspapers in Great Britain as well.3 This case illustrates the degree to which media coverage can be swayed by the point of view of the journalist reporting on the terrorist activity. Use of the word terrorism is usually reserved for attacks against the population of the reporting agency, while other attacks that take place in foreign countries are often described using different terminology.

Moreover, because there is no clear and accepted definition of terrorism, the term is sometimes used to describe and portray events that have nothing to do with terrorism per se, such as: violence and instilling fear that has no political background, criminal action perpetrated for economic reasons, etc. The use of the term terrorism in those cases is intended to endow these incidents with a negative connotation.

In the past, several attempts have been made to reach an international definition of the term terrorism. It is interesting to note that among the nations that were active in the effort to define terrorism are those known for their clear support of the practice—Syria and Libya. In August 1987, a conference of the Arab League was convened in Damascus in order to formulate a definition of the concept of terrorism for submission to the UN General Assembly. The Syrian foreign minister stated in his speech at the opening session that establishment of the committee was “a positive turning point in defending the Arab people from the evil Zionist-Imperialist attacks.”4 In October 1987, the Libyan ambassador to the UN (and chairman of the Legal Committee) officially proposed in the committee that the UN initiate an international conference on terrorism which would be convened, among other things, for the purpose of reaching a new definition of the term “terrorism.”5 Such initiatives are indicative of the tremendous importance that states sponsoring terrorism attribute to its definition, since the attempt to reach a definition will allow them and their allied terrorist organizations to remain free of any direct responsibility for terrorist attacks and to evade punishment.

Figure 1.1

Defining Terrorism as a Fundamental Counter-Terrorism Measure

In January 2001, during discussions of the UN Ad-Hoc Committee on International Terrorism, India submitted a document that attempted to formulate a definition for the term terrorism.6 In later discussions at the UN, which were held following the events of September 11, that definition was rejected. This example also illustrates the difficulty involved in reaching an internationally agreed upon definition for the term.

According to those who oppose any definition, the decision makers—and certainly security establishments—get along quite well without an accepted definition for terrorism based on the assumption that “when you see terrorism you know it is terrorism.” Terrorists, they claim, are essentially committing ordinary criminal acts—they extort, carry out arson, murder, and commit crimes that are prohibited according to the standard penal code. Therefore, they can be brought to justice without needing to define a crime that particularizes terrorism. This argument is also voiced with regard to international legislation. The accepted trend in this sphere during the past decades maintains that terrorism can be addressed more successfully from a legal and normative perspective, through legislation that prohibits specific actions, such as airplane hijackings, diverting shipping and marine piracy, setting off explosive devices, etc.—without the need to define what terrorism is. Nor is there any need to reach agreement regarding the concept of terrorism when it comes to intelligence and military cooperation on an international level, because the discourse between countries focuses on specific organizations and activists, and thus the political dimension of any definition can be avoided.

In contrast with this school of thought are those who support the need for an international definition of terrorism. They believe that not only can terrorism be defined objectively and agreement be reached on the nature of the phenomenon, but that without such a definition it is impossible to mount an effective international fight in this arena. According to this approach, numerous spheres of international cooperation that are not necessarily related just to intelligence or military activity require a consensus on the definition of terrorism. Any attempt to “shut off” the financial sources of terrorist organizations; to prevent the recruitment of new activists to their ranks; to thwart attempts at transferring and “laundering” money; to stop terrorists and extradite them from one country to another; to deal with countries and communities that support terrorism; and above all, to formulate a normative and binding system that defines rules for what is permitted and forbidden, what is legitimate and illegitimate—all these necessitate an unequivocal and objective definition of terrorism based, as broadly as possible, on international agreement.

Without a definition for the concept of terrorism, the world’s leaders can gather, as they did at Sharm el-Sheikh in 1996, and in an extraordinary but essentially meaningless gesture, hold each other’s hands and wave them aloft and announce together far and wide that they are opposed to terrorism. This, of course, without defining what terrorism is. In the absence of a definition, countries like Syria and Iran can loudly proclaim that they do not support terrorism—they support the “national liberation” of oppressed peoples.