- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Adolescent Stress concentrates on a range of major problems—those of a normal developmental nature as well as those of poor adaptation—identified in adolescents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adolescent Stress by Mary Colten in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Adolescent Stress, Social Relationships, and Mental Health

Susan Gore and Mary Ellen Colten

In this volume we bring together a series of papers that focus on the multifaceted nature of adolescent stress and its consequences for mental health and well-being. The topic, of course, is timely, in light of documented increases in rates of both suicide (Murphy & Wetzel, 1980; USDHHS, 1986) and depression (Klerman & Weissman, 1989) among adolescents and young adults. The high rates of substance use and abuse in junior high and high school aged youth (Wetzel, 1987; Johnston, O’Malley & Bachman, 1987) as well as other risk-taking behaviors are negative health outcomes in and of themselves, and reflect the dysfunctional strategies many youth use (Huba, Winegard, & Bentler, 1980) to cope with stressful life conditions and emotional distress.

The concept of stress is an important tool for organizing research seeking to understand development during the adolescent years, how development is shaped within the wider contexts of individual experience and societal forces, and the processes that lead to well being on the one hand or to distress and life problems on the other. The thirteen papers in this volume consider stress and adaptation during the adolescent years in the broadest possible way, drawing on key concepts and the wealth of existing research across a number of disciplines. In combination, they characterize the origins, nature and means for addressing some of today’s most vexing problems.

There is already such a rich body of research on child and adolescent mental health (see the special issue of the American Psychologist, 1989) that we should first consider the place of this volume in the larger field and characterize its special niche. In many ways the volume reflects continuity within established lines of investigation. Several of the authors are senior researchers in the field of adolescent mental health and have developed some of the major frameworks and data sets (Dornbusch et al., 1985; Petersen & Spiga, 1982; Brooks-Gunn, 1987; Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1984) for conceptualizing and studying the interrelationships among development, stress, and mental health. In addition, many of the papers reflect an underlying concern with the twin concepts of risk (exposure to stress) and resilience (resistance to stress), which have been a critically significant organizing tool for theory and research on child mental health (Werner & Smith, 1982; Rutter, 1979; Anthony, 1974; Garmezy, 1981; Felner, 1984). Finally, in keeping with much of the research on the developmental “tasks” of adolescence (Hamburg, 1974; see Petersen, 1988, for a review) and on the transformation of parent and peer relationships during these years (Youniss, 1980), the papers highlight both positive and negative processes in relationships with family and peers, yielding clues to the complex dynamics between stress and social support processes that are the subject of much current research attention. In these and other ways, this volume is clearly informed by significant existing traditions.

At the same time, these papers speak from new data, methodologies, and ideas, departing from these established traditions in several ways. First, they envision both stress and adaptation as occurring along a continuum ranging from “low-risk” normal developmental processes to potentially more maladaptive “high-risk” situations that constrain coping resources and place youth at even greater risk for other difficulties and a problematic life course. Although the papers implicitly and explicitly concern adolescent mental health, the diverse perspectives taken do not seek to provide a profile of optimal behavior or of psychopathology. Rather, as Powers, Hauser, and Kilner note (1989, p. 201), there is much need for dialogue that can help to “define the limits of the range of functioning that is adaptive in adolescence.” The papers address this need and also elucidate individual and subgroup differences, which, as Powers and associates also note, should facilitate discovery of various patterns of positive mental health. In this way, the papers also draw our attention to the many conceptual and operational definitions of both the independent variable, stress, and the dependent variable, adaptation, thus broadening our definitions of each.

The papers also report on a wide range of populations, including representative cross-sections of community populations and convenience samples of both well and troubled youth, underscoring the importance of considering the gamut of stress responses that define mental health and well being in the adolescent years. According to Aneshensel (1988), this attentiveness to a number of theoretically relevant stress responses contrasts with the disease-specific orientation of etiological research that is often superimposed on stress research. Unfortunately, many of the major studies of life stress have focussed on a single dependent variable, making it impossible to chart alternative expressions of distress and the clustering of multiple risks and problems in the same individuals. This volume accords an important corrective by considering a range of stressors and outcomes and providing frameworks for understanding processes both specific to and across diverse populations of youth.

Another special feature of this volume is the attention given in several chapters to understudied populations of at-risk adolescents such as runaways, victims of child abuse, gay, educationally handicapped youth, and teenage mothers in a drug-centered social milieu. Understanding the social situation and mental health of youth in these groups is important in its own right, and draws our attention to the importance of interventions for youth who are not only at-risk, but also for those who have already experienced significant mental health and behavioral problems and other trauma that jeopardize their futures. Too often these groups are studied only from a problem-oriented perspective that ignores the larger context, uninformed by either of the traditions of stress or developmental research. At the same time, the extreme adversity faced by these youth forces us to reconsider some of our existing models of developmental stress, an issue we will address later in this chapter.

Finally, the range of topics and formulations advanced in these chapters is the direct result of our effort to select authors who represent a number of disciplines with unique concepts and concerns regarding stress and development and, in each case and as a whole, the papers reveal the potential for cross-fertilization of several rather distinct lines of investigation. In the Editors’ summary that precedes each section of readings we will emphasize the specific perspectives and contributions of each reading, and suggest linkages and further ideas generated by the group of papers as a whole. Also, in the final section of this introduction we will present an overview of the volume’s organization, but here we would first like to return to the issue of the many understandings of adolescent stress processes, considering several of the ways in which a more coherent field of adolescent stress research follows from the integration of child and adolescent development studies with life stress and coping perspectives on mental health.

Development, Stress and Mental Health

As noted above, there are many different conceptual and operational definitions of stress in the volume chapters. An important distinction lies in whether stressful life transitions and experiences are seen as stemming directly from adolescent development or whether the life stresses of adolescents, rather than of adolescence, are being studied. These italicized terms convey the distinctive emphases of the life stress and child development fields, which have differed significantly in their orientation, while sharing a focus on the problems of adaptation during the adolescent years. Life stress researchers have most often emphasized study of non-normative stressful life events, that is, stressful experiences that can happen to different people at different times. In seeming contrast, developmentalists have taken life stage as the point of departure, seeking to understand—in the case of adolescence—the normative developmental changes that all youth experience. Some of these life transitions are experienced with a cohort, such as the change from elementary to junior high school, while others, like pubertal change, have a variable timing within the age cohort. Interestingly, this feature of variable timing can turn “normative” events into “non-normative” events for individuals, providing a basis for studying the non-normative nature of some transitions for subgroups of individuals, and thus suggesting greater similarities between stress and child development research than are often recognized.

These two traditions have always shared a common concern with the two fundamental problems in the study of risk and resilience: (1) establishing the influence of stress on mental health—the study of stress exposure and its effects, and (2) uncovering processes that mediate these stress responses, as well as those that determine resilience or vulnerability by moderating or “buffering” the effects of stress. Despite this mutuality of concerns, early research in both the life stress and adolescent development fields was narrowly focussed. In the life stress field, an initial understanding of stressors as “fortuitous” or “eventful,” and as influencing health status only in the aggregate, discouraged sensitivity to the distinctiveness of life experience and stress for different population subgroups and at each stage in the life course. As noncontextual as this “pure stress” research model was, the early “pure development” research orientation was its match. Petersen and associates remind us in their chapter that early research on adolescent stress was guided by the hypothesis that the hormonal changes of puberty were solely responsible for psychological status during early adolescence, a view that exemplifies this disregard for social context as well as other individual variables.

The papers in this volume demonstrate the considerable movement toward convergence of interests and a mutual strengthening of developmental and stress research traditions. Progress is evident in modeling the interrelationships between the myriad of developmental and nondevelopmental stresses experienced by adolescents. For example, from developmental perspectives, Rutter (1979) and Simmons and colleagues (Simmons, 1987; Simmons, Burgeson, Carleton-Ford, & Blyth, 1987) have been concerned with the effects of simultaneous developmental changes, in contrast to singular developmental events, as their evidence shows that particular transitions by themselves do not pose a major threat for most youth, but that transitions in the context of other developmental events can increase the risks for some. This shift in research orientation has great theoretical and practical potential, as this may be an important basis for differentiating high and low risk populations, and between situations that are likely to be challenging to youth and promote mastery experiences, versus those that are overwhelming and cannot, objectively, be mastered.

The problem of coming to grips with the linkages between development, stress and context is not limited to the tradition of child and adolescent development studies. The paper by Compas and Wagner in this volume, takes the framework of stress research as its point of departure and seeks to enrich this perspective through attention both to age differences and the developmental relevance of different clusters of stressors. Specifically, their data establish that the pattern of correlations between the kinds of stressors and symptoms of distress for different age groups follows a developmentally meaningful pattern: only negative family events predicted to distress in the junior high sample, only negative peer events in the high school sample, and only negative academic events were predictive of distress in the college sample.

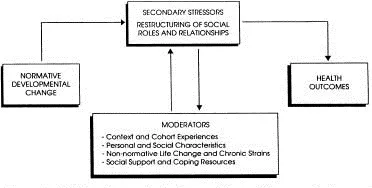

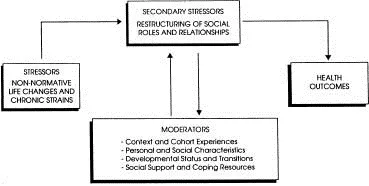

In each research tradition, whether developmental or other stressers are the point of departure, questions about the overall stress context are highlighted. What are the other stressful events and conditions in the lives of adolescents that add to or interact with a particular developmental or nondevelopmental stressor? This problem of the multiple stress arenas of adolescent functioning must be distinguished from a different contextual issue, namely the importance of protective factors, such as social support or individual characteristics, that promote resilience in the face of stress. These are usually understood as moderator variables, and they are another piece of a complex picture that is illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1Health effects of developmental transitions: mediating and moderating processes

Figure 2Health effects of life stress: mediating and moderating processes

These two figures are identical in depicting key aspects of the stress process, but they differ in one important regard, which is whether developmental stressors or other non-normative stressful life events and conditions should be modeled as the independent variable or the moderator variable. Figure 1 depicts a concern with the effects on adolescent health of a particular normative developmental change, such as a school transition, which occurs in the context of other life stresses, such as parental divorce, or other developmental changes (e.g., puberty). Here we are investigating the conditions under which a transition such as school change has a negative versus a benign or even positive influence. In Figure 2, our perspective is somewhat modified, in that we now ask whether the effects of non-normative life stresses are conditional upon other contextual and individual factors, including developmental stages or transitions. For example, this has been an important question in research on the effects of parental conflict and divorce on children’s mental health (Emery, 1982). Much research documents that the nature, severity and persistence of children’s negative responses to life stresses within the family domain are dependent on the developmental status of the child.

Moreover, it is important to keep in mind that many subgroups of youth face extremely adverse life conditions, such as poverty, a climate of violence or familial homelessness. For these youth it is not entirely appropriate to focus on the processes in Figure 1, that is, the relationship between developmental changes and health and behavioral outcomes, since the effects of major nondevelopment related risk factors are clearly more influential in shaping their mental health than are developmental transitions. In addition, models of developmental transitions, such as that depicted in Figure 1, assu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Editorial

- Title Page

- About The Editors

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Introduction: Adolescent Stress, Social Relationships, and Mental Health

- Part I. Editors' Overview Development, Stress and Relationships

- Chapter 2. Anger, Worry, and Hurt in Early Adolescence: An Enlarging World of Negative Emotions

- Chapter 3. Conflict and Adaptation in Adolescence: Adolescent-Parent Conflict

- Chapter 4. Psychosocial Stress during Adolescence: Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Processes

- Part II. Editors' Overview Sources of Variation in Stress and Stress Responses

- Chapter 5. Coping with Adolescence

- Chapter 6. Stressful Events and Their Correlates among Adolescents of Diverse Backgrounds

- Chapter 7. How Stressful Is the Transition to Adolescence for Girls?

- Part III. Editors' Overview Youth at Risk: The Social Situation and Mental Health of Adolescents Under Adversity

- Chapter 8. The Patterning of Distress and Disorder in a Community Sample of High School Aged Youth

- Chapter 9. Minority Youths at High Risk: Gay Males and Runaways

- Chapter 10. Childhood Victimization: Risk Factor for Delinquency

- Chapter 11. Psychoactive Substance Use and Adolescent Pregnancy: Compounded Risk among Inner City Adolescent Mothers

- Chapter 12. Stress in Mentally Retarded Children and Adolescents

- Part IV. Editors' Overview Strategies for Intervention

- Chapter 13. A Multilevel Action Research Perspective on Stress-Related Interventions

- Chapter 14. Social Support in Adolescence

- Biographical Sketches of the Contributors

- Author Index

- Subject Index